How a group of friends in quarantined Palestine started a radio station

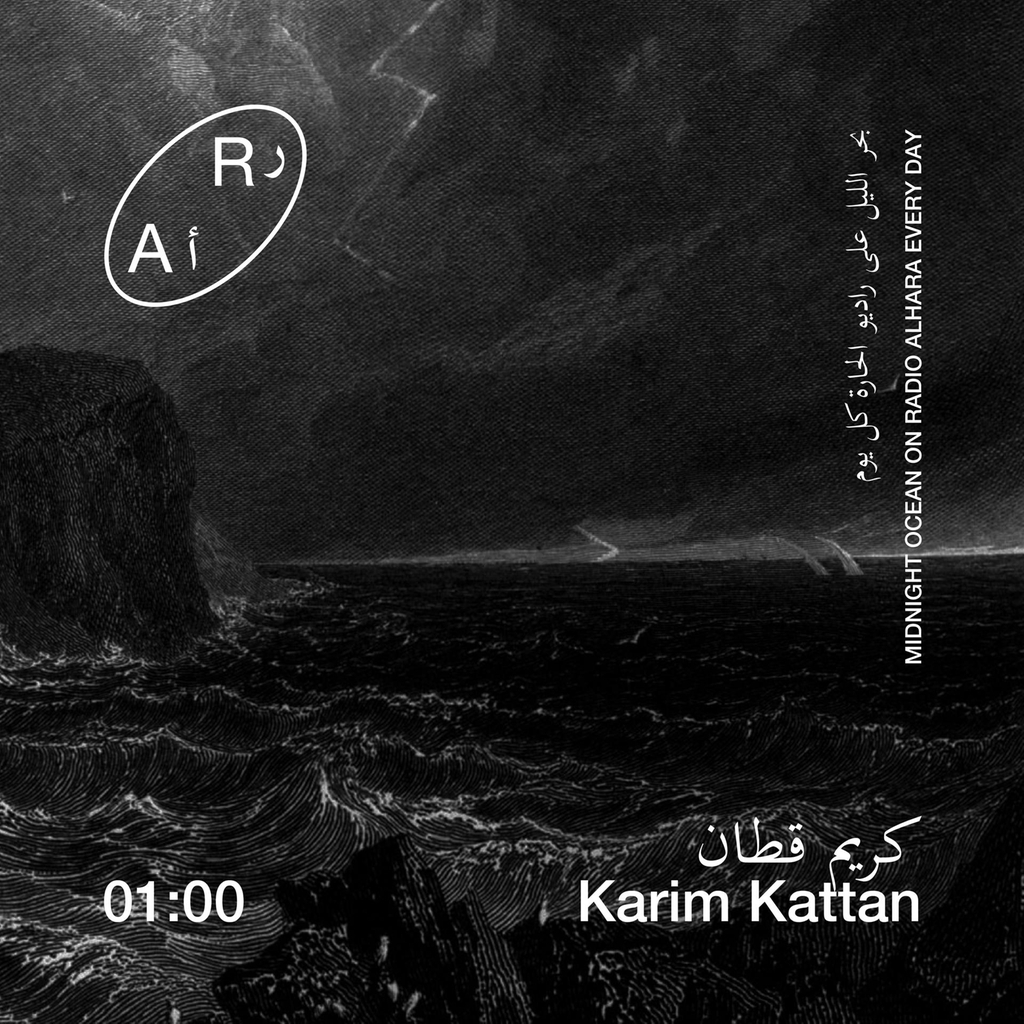

It’s just gone 9am in London and Miles Davis’s ‘Round Midnight’ (1957) is on the radio. A mellow way to start the day. The record ends and two softly spoken DJs have a conversation in Arabic about Davis and – as far as I can work out – about the next track, Frédérick Chopin’s first waltz for solo piano, the ‘Grande valse brillante in E-flat major’ (1833). Where exactly the two men are speaking from is unclear, but the radio station, Radio Al Hara, is being broadcast over the Internet from home studios set up in Ramallah, Bethlehem and Amman.

The languorous breakfast slot – or a chilled mid morning in Palestine – is abruptly interrupted by Smif-N-Wessun’s ‘Bucktown’, the 1994 hip-hop track heralding a higher energy set courtesy of Elias Anastas. The DJ, whose day job is in architecture, founded Al Hara in March with his brother Yousef, as well as Ramallah-based artist Yazan Khalili and Amman-based designers Mothanna Hussein and Saeed Abu-Jaber, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. They say they were inspired by a rash of community radio stations that have been set up since the onset of lockdowns in the region including Radio Al Hai in Beirut and Radio Al Huma in Tunis. Similar ventures have appeared further afield, including Radio Zona Rossa broadcast on local frequencies in Codogno, Italy, by 83-year-old Pino Pagani; Quarantine FM in Dublin, which as well as music and discussion, has included children’s programming; and Radio Quarantine, set up by sound artist Yashas Shetty and members of the Indian Sonic Research Organisation, a network of independent instrument builders in Bengaluru. In Britain curator Jonathan P. Watts has been broadcasting nightly sessions as Radio Caroline over Twitch including sets by artist Ryan Gander.

The idea to start a Palestinian lockdown radio station followed a discussion between the Anastas brothers bemoaning the loneliness of the necessary social distancing measures, together with a frustration at the response from preexisting cultural institutions, which typically poured out online content in a bid to maintain visibility. Elias told The National: ‘It was overwhelming. We are tense, we are worried – you cannot sit and watch an experimental film.’ Instead, Al Hara – which means ‘the neighbourhood’s radio’ in Arabic – was to become a place of escape and community: many of the shows are made by the listeners themselves, uploaded to Dropbox as a digital file for later broadcast. Azim Fathi, founder of Iranian electronic music label Paraffin Tehran, has produced a show of pre-revolution pop; Hasan Hujairi has explored the histories behind the Wātrembo, a women’s song sung at weddings in Bahrain; and economist Raja Khalidi led a discussion on what the financial situation of the post-pandemic Arab world might look like.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Palestine has been undergoing what Rasha Kaloti has described as “a nightmare within a nightmare” – the Jerusalem-based public health specialist goes on to note how the degraded healthcare system and severe overcrowding in the state present a terrifying cocktail. Yet the worst fears concerning the new coronavirus have not yet come to be realised. Cases in Palestine have numbered just 485, with three deaths, in part due to the early implementation of social distancing measures, first in Bethlehem and then in the rest of the West Bank. Instead the biggest problem for Anastas and his collaborators has been the universal one of lockdown boredom.

Al Hara is not overtly political but inevitably the unique situation and history of Palestine feeds into its programming. Official, licensed, Palestinian-run radio stations are a relatively recent thing after all, a result of the Oslo Accords between 1993 and 1995. Prior to then, residents of the territories had to make do with the Arabic language services of the Voice of Israel, the BBC and the French Radio Monte Carlo Doualiya, or, more likely, would tune into various pirate stations that sprung up as part of the struggle against Israeli occupation. The heavy curtailment of freedom that characterises Palestinian life even outside of a pandemic, as well as the everyday violence of the occupation, lends an added pathos to the freedom embedded in the station’s programming.

Nor is political discussion entirely banished. The previous day, I tuned in midway through a conversation on the wild pig situation in Palestine: the animals regularly decimate the crops of Palestinian subsistence farmers, feeding on waste dumped by Israeli settlers. “This is a symptom of the settler-colonial relationship” one of the guests said. “It touches on questions of property, gendered engagement, and brings into focus the construct of Palestinian social space.” The speakers dismissed conspiracies that the animals were introduced on purpose as an invasive species but note that the situation might be likened to Rob Nixon’s concept of ‘slow environmental violence’. Listening from over 3000 miles away, this everyday annoyance brought home the mundane micro-aggressions of the occupation beyond the more dramatic events that might make it to international media.

As I write this, Anastas’s session picks up pace with a tracklist heavy on records by black American artists. Here’s The Notorious B.I.G., here’s Don Theking. Up comes Theophilus London’s ‘Last Name London’. If the station, and those like it, needed an anthem, the Trinidadian-born American rapper’s 2011 work might serve it well.

It’s more refresh a breath could be

And if you don’t know I tell you what’s next for me, for me

From a bird’s view, from the third view

In the sky without no curfew