‘I was young and beautiful and that got me what I wanted, and all I wanted was sex.’

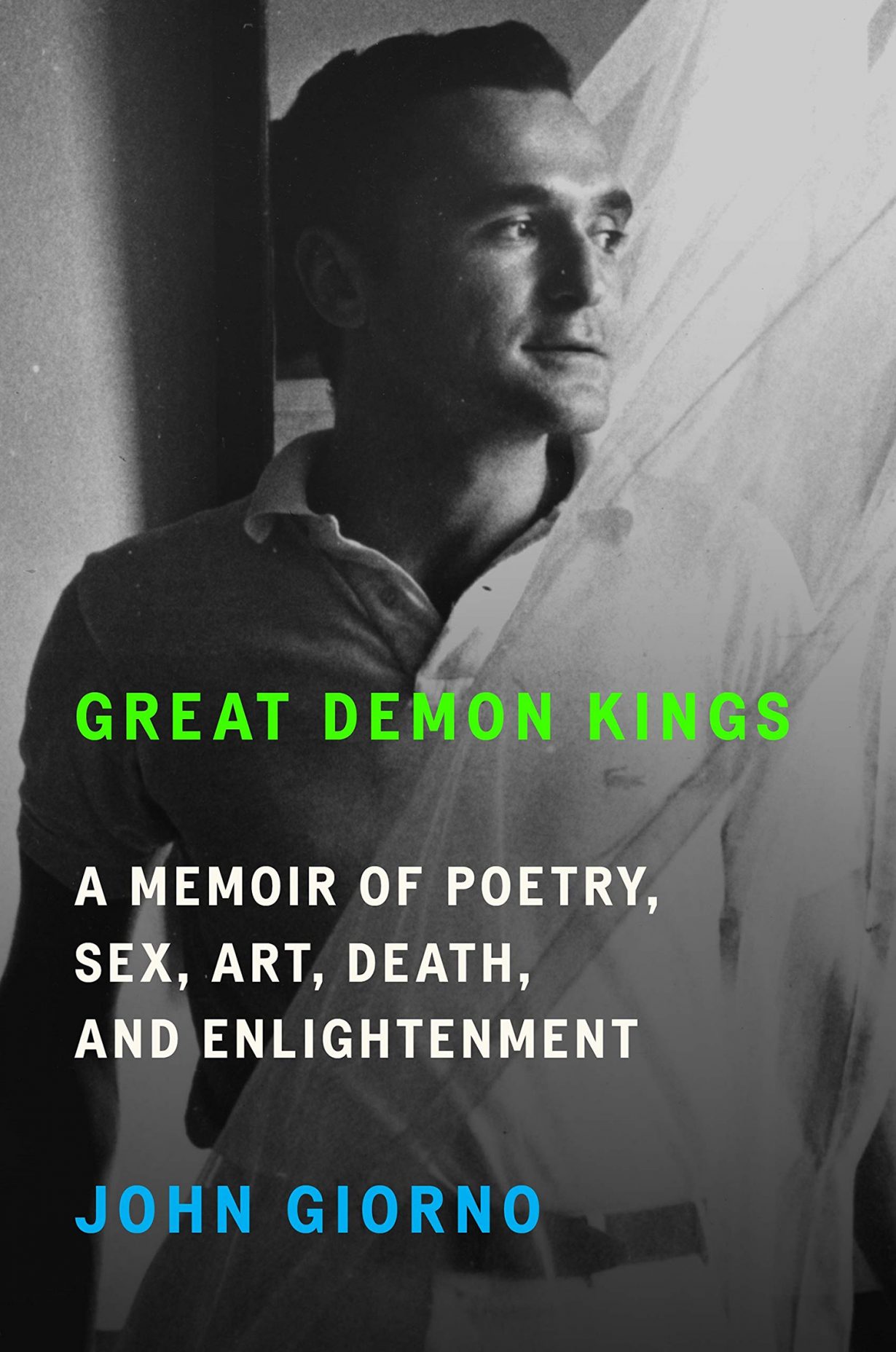

In the opening chapter of John Giorno’s posthumous autobiography, Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment – published this week – he describes the euphoria that washed over him the first time he read Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ (1956). Giorno, who died last October, was no stranger to poetry, having had his own talent as a writer identified while still a high school student, but ‘Howl’ was something else entirely: up until his reading of the Beat poet’s most famous work (he was stoned at the time, he tells us), his connection had been academic. He recalls, slightly misty-eyed, a chance meeting with Dylan Thomas at a reading a week prior to the Welshman’s death, and he admits a youthful love for T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ (1922), but all that paled next to the raw emotion Giorno found in Ginsberg’s epochal ode to drugs, sex and social freedom.

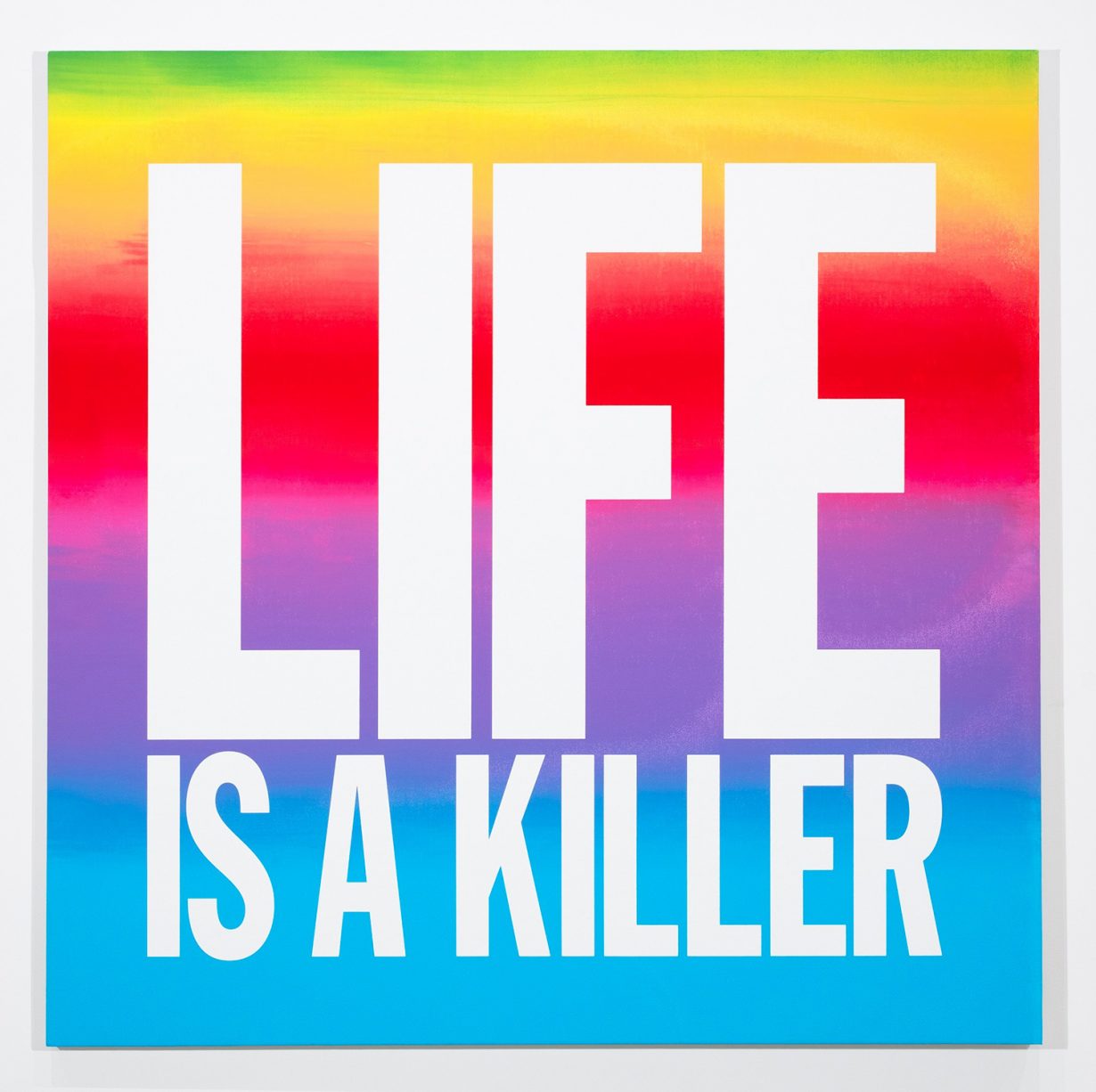

Giorno goes on to write that attempts in his later years to get younger readers interested in ‘Howl’ were met with ambivalence – a respect for its import, but not the visceral reaction he’d had. ‘It no longer has the power to liberate… its cultural moment has passed,’ he concludes. I feel something similar in response to Giorno’s long-form poetry (as opposed to his sparkier, fresher Poem Paintings) and to his generation of American artists, 1960s revolutionaries whom we’re supposed to revere but whose art I look upon with intellectual, art historical, curiosity only; any emotional response, any shock of the new, blunted by the years of academic output lying like dust on the objects themselves.

Yet despite my own ambivalence, I find myself writing about many of the artists in Giorno’s circle time and time again. Partly this is in response to vestiges of American cultural hegemony that still resonate, and partly it’s a consequence of my work penning obituaries. The US during the late 1950s and early 1960s was at the apex of the avant-garde, and nowhere more than New York, home to a productive mix of displaced peoples yet with none of the long shadows war still cast over Europe. But another reason for my continued attention to this period reflects the fact that the artists of this time ushered contemporaneity into art, and the notion, dear to me, that art was something for the moment, ephemeral and transitory.

At the time of his Beat poetry enlightenment, Giorno was, he writes, ‘young and beautiful, and had all I wanted, and all I wanted was sex’. These attributes were a passport to the most fashionable parties and encounters with a who’s who of twentieth-century US culture. The list of friends and lovers, many of whom he collaborated with at ‘the Bunker’, the studio complex Giorno established on the Bowery (described by The New York Times in 1965 as ‘a vision of Montparnasse replacing Skid Row’), is mesmerising: John Cage, Anne Waldman, Mark Rothko, Lynda Benglis, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Trisha Brown, Carolee Schneemann, Bernardine Dohrn of the Weather Underground, Bob Moog of Moog-synthesiser fame. Giorno toured the States with William Burroughs, performing poetry through the 1970s and 80s (the book also contains a vivid description of their sexual liaisons); he is perhaps best remembered as the subject of Warhol’s Sleep (1964), the first film by the artist, whom Giorno was dating at the time.

The audiobook version of the autobiography is notable for its addendum of three works by Giorno, one of which is the interview conducted for Pierre Huyghe’s Sleeptalking (d’après Sleep) (1998). The younger artist’s film recreated the Warhol work some three decades on, the slumbering Giorno still handsome but older now. In the interview, recorded over several visits Huyghe made to the Bunker, the artist reminisces about his life and the context of the original Sleep. If Huyghe’s collaboration was autobiography in the form of an artwork, here we have the narration removed from the original context and inserted into an actual autobiography. It introduces themes of ageing and dying; it places the artwork, both the original and this sort-of remake, within their specific cultural moments. The other audiobook ‘extras’ are readings of ‘There Was A Bad Tree’, a parable about a noxious tree that produces treasure when treated with care; and ‘THANX 4 NOTHING on my 70th Birthday in 2006’, in which the poet, speaking slowly and with deliberation, each syllable enunciated, again looks back on his life.

One line in this last piece stands out: “May you smoke a joint with William / and spend intimate time with his mind / more profound than any book he wrote”.

As with Burroughs’s works, Giorno’s art had its source in a social scene from another time. It was a reaction to a context now lost, and encountering it now can be a bit like reading a letter from the last days of Rome, entertaining but alien.

Nonetheless, Giorno can be credited with foregrounding the artwork as a social object, and for this we should be thankful, even if it’s to the detriment of his own legacy. Here the artwork is alive only as long as the network of connections that gave rise to it remain intact, connections impossible to truly preserve or maintain over time, to restore or interpret in retrospect. If this is art that dies once its work is done, it raises all sorts of questions about art’s purpose. Necessary, urgent ones concerning the responsibilities of its guardians: is it the preservation of a dead past, or duty to the complicated present?

Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment is published in hardcover by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and as an audiobook by Macmillan Audio