The ghosts of the artist’s 1986 film – available to watch this week – have not been exorcised

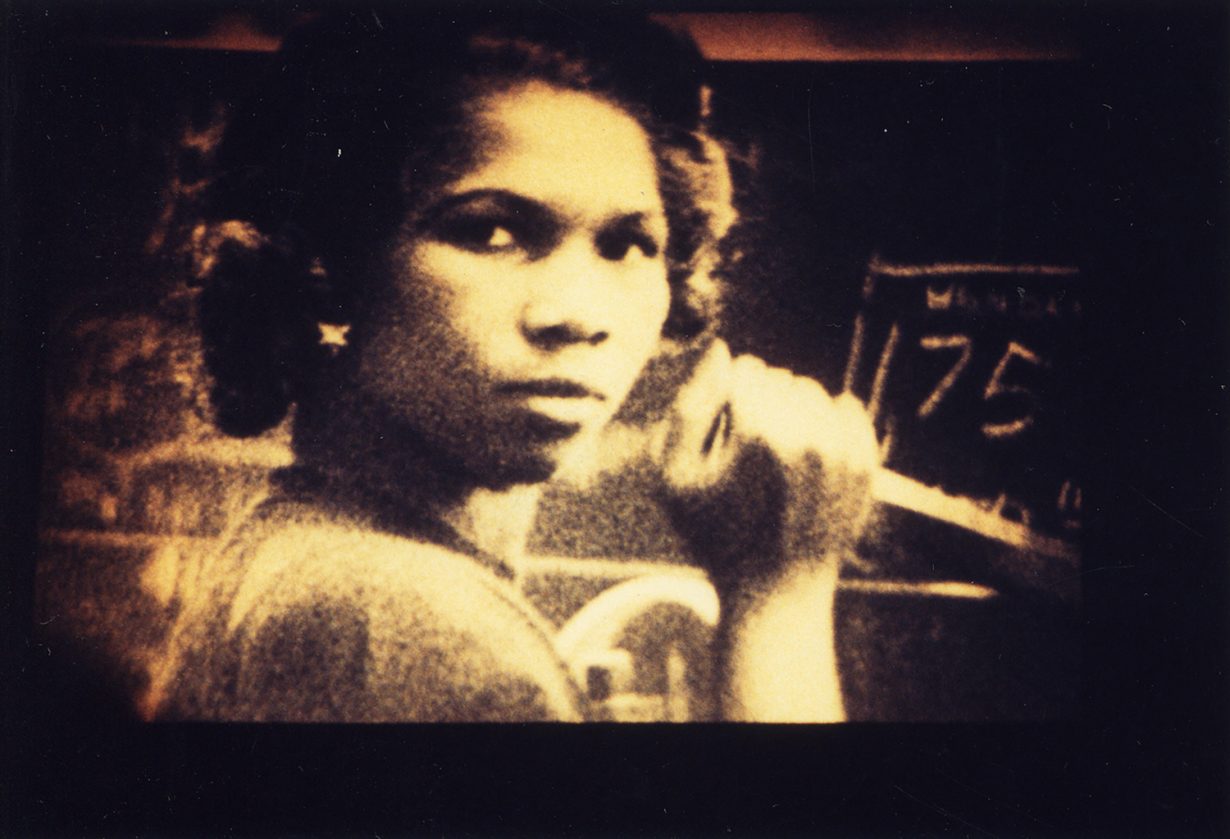

“There are no stories in the riots, only the ghosts of other stories.” So said a local woman to a journalist pestering her for an eyewitness account of the 1985 Handsworth Riots. The dialogue is retold in the Black Audio Film Collective’s Handsworth Songs (1986), directed by the British artist John Akomfrah, which follows the unrest that burned for three days through the Birmingham neighbourhood, in a loose documentary format. That year, black communities came out onto the streets across Britain to protest heavy-handed policing, police killings and the racist politics of the Thatcher government. A few weeks after Handsworth, Brixton in London erupted when a black woman, Cherry Groce, was shot in the course of a police raid, as did the Broadwater Farm estate in the north of the city following the death of Cynthia Jarrett in another house search.

The ghosts that haunt those street fights, and hang heavy in Akomfrah’s film, which was made available online for a week, are of poverty, colonialism and the betrayal of the Windrush generation. The woman being interviewed amongst the debris recalls the racist rhetoric of Enoch Powell; she remembers when Malcolm X strode through the grey streets of Smethwick, in the West Midlands, in 1965, just nine days before he was assassinated. Akomfrah records less dramatic racism, but every bit as insidious: Douglas Hurd, then home secretary visits the scene, broken glass still underfoot, and sympathises with a white crowd of bystanders. “It must have been a scary experience,” he says. Margaret Thatcher, in an interview, warns against further immigration: “The moment a minority gets a big one, people get frightened.” A young Asian community worker describes how a new police commissioner, intent on getting tough on hard drugs, has initiated a tsunami of searches of young black men and raids of predominantly black pubs and parties, without evidence or success. “It’s obvious, you can’t have young rastas flying over to India and Pakistan collecting heroin. Afro-Caribbean and young Asian youth don’t have the kind of money to push those types of drugs. Those drugs are being brought in by organised, criminal, businessmen.” The police continued their harassment, evidence be damned.

Yet they are ghosts that have not been exorcised. Originally commissioned by Channel 4 in the UK, 25 years later, in September 2011, Tate Modern showed the film again. That event was programmed in response to a wave of protests and riots across the country after the police shot Mark Duggan, a black man in north London. Akomfrah, alongside his collaborators, Lina Gopaul and David Lawson, took part in a conversation with the academic Kodwo Eshun as shops were destroyed across the city and justice was demanded. The late theorist Mark Fisher was in the audience, later writing for Sight & Sound: ‘Watched – and listened to – now, Handsworth Songs seems eerily (un)timely. The continuities between the 80s and now impose themselves on the contemporary viewer with a breathtaking force: just as with the recent insurrections, the events in 1985 were triggered by police violence; and the 1985 denunciations of the riots as senseless acts of criminality could have been made by Tory politicians yesterday.’ Lisson, the gallery which represents Akomfrah, uploaded the film this week, nine years on, 34 years after it was first shown, as Britain’s streets are once again – again – filled with anger at the racism that lingers in every facet of the country. This time it was the death-by-cop of an American, George Floyd, that amplified the call that Black Lives Matter in Britain too. Tory politicians and commentators once again lined up to denounce the protests. Prime minister Boris Johnson urged people not to protest, claiming that the movement had been ‘hijacked’ and would likely ‘end in deliberate and calculated violence’. The toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol, a man who made his money in the slave trade, was ‘utterly disgraceful’ decried home secretary Priti Patel. Akomfrah once again put in conversation, this time in a Zoom discussion conducted this week.

Akomfrah’s work was broadcast (back when Channel 4 broadcast such things) in the white heat of the Handsworth unrest, but its subject is not confined to the events of those three late summer days. Instead it tracks how we, Britain, got there. And how we got to where we are now. It’s a vital film, not just for its reflections of the myth of the ‘good immigrant’, of integration (the “h’integration” that the Black-Brummie comedian Lenny Henry would claim his mother saw as being of paramount importance), but it also throws up the nuances that separate the history of British racism from its American mode. Akomfrah’s film does not just feature black and and white faces (the latter always in positions of power: police, politicians, reporters, clergy) but gives voice to the area’s Asian community too. They speak as victims (two Asian men, Kassamali Moledina and his brother Amirali, died in a fire; many Asian people owned shops damaged in the protests) and mediators. In a recent essay, Gary Younge noted the dangers of Europe focusing its attention on American racism at the cost of its own. ‘Well into my thirties, I was far more knowledgeable about the literature and history of Black America than I was about that of Black Britain, where I was born and raised, or indeed of the Caribbean, where my parents are from. Black America has a hegemonic authority in the black diaspora’ he writes. America is racist because it owes its foundation to religious zealots determined to make a new world even more puritanical than the old one they had left, a new world they built off the back of black slavery. Britain is racist because we got in boats, sailed far from our own shores, to murder, pillage and enslave peoples in Africa and Asia. When the exploited nations started to turn up on this country’s doorstep, it was as if the ghosts of its past had arrived for a reckoning. Handsworth Songs is a brilliant work; but its return, its own haunting – rerun time and again as our rotten history is never resolved – is as unwelcome as it is necessary.