The artist’s ode to black American struggle – streaming online this weekend – is imbued with a powerful, but conflicted, pathos

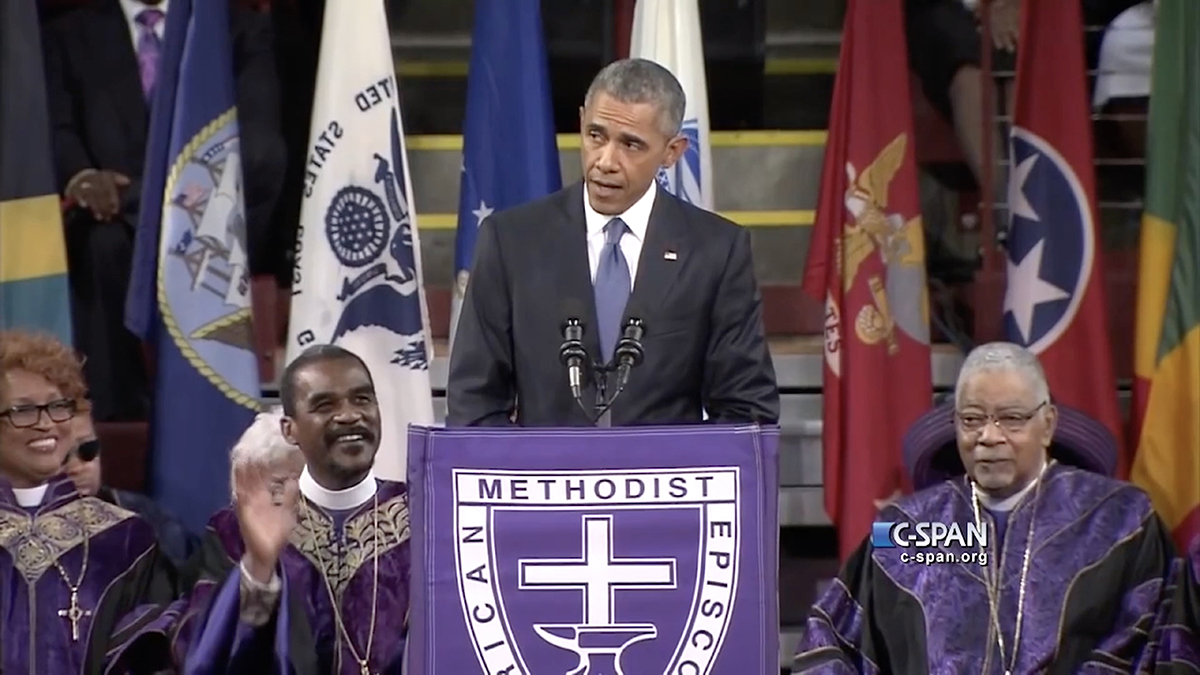

When Arthur Jafa’s seven-minute videowork Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death debuted in 2016, it elicited immediate, powerful responses. The artist’s gallery, Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, in New York, received unprecedented visitor numbers, and the film went on to tour (and be bought by) institutions internationally. To the soundtrack of Kanye West’s gospel-inflected hip-hop song Ultralight Beam (2016), the artist collages a century’s span of images showing African-American triumphs – academic, political, sporting and cultural – interspersed with footage of the violence, arrests and other aggressions meted out on America’s black population by the police. Added to this montage, which stretches from the Jim Crow era to the aftermath of Michael Brown’s killing by police in Ferguson, Missouri, is home footage of Jafa’s own family. In the resulting film, the emotive music, the slowing down of film speeds and the careful jump cuts ensure that there is no hierarchy to the empathy with which the artist treats the individual images: celebrity, historical, family or poor, the same structural racism abounds.

Now, four years on, amid further graphic evidence to the contrary, US streets and increasingly the culture at large are ringing out with the cry that Black Lives Matter (a message resonating powerfully beyond US borders too, it should be said). Marking these latest convulsions, Jafa’s work is to be streamed online this weekend by 13 art institutions internationally, including the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, the Tate in London and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

The story of Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death is a mixed one, however. Jafa himself has expressed ambivalence about the impact the work has had. ‘I started to feel like I was giving people this sort of microwave epiphany about blackness,’ he told The Guardian in 2018. ‘I started [feeling] very suspect about it. After so many “I cried. I crieds”, well, is that the measure of having processed it in a constructive way? I’m not sure it is.’ Rewatching the video it is easy to understand Jafa’s concern. It is without doubt moving (I can’t remember if I cried the first time around, maybe, probably: it’s a subject worth crying about); it is also manipulative. Jafa also works as a cinematographer, and has a long list of music video and feature film credits, so he knows how to use film and music to elicit a reaction. Another reason Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death has resonated so widely has to do with the global familiarity of the footage, even that which we might never have seen before (of course, there’s a side issue in this: where once the world was colonised by symbols of so-called American freedom, from Levi’s to Coca-Cola, international audiences today often respond to US cultural imperialism by cosplaying American trauma rather than confronting entrenched racism closer to home).

Those who could bear to watch the George Floyd video did so knowing the outcome, having seen this horrendous form of documented killing proliferate on our screens in recent years, and it is a familiarity Jafa deploys extremely effectively in his work. In 1957 Howard D. Gould told readers of his column in The Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper, ‘Under the spotlight of TV, discriminatory practices will have to stop’. Gould was only correct to a point. Undoubtedly the ubiquity of camera phones has helped expose the racist killing of black people, but in the proliferation of that imagery lies a problem Susan Sontag identified: ‘Photographs of the victims of war are themselves a species of rhetoric. They reiterate. They simplify. They agitate. They create the illusion of consensus.’ Jafa’s point in that 2018 interview neatly summarises the danger of allowing a white audience a moment of pathos, a moment of consensus; it risks stifling action. You’ve watched the pain, you’ve shed the tears; now what are you going to do?