Pearamon Tulavardhana, met by guerrilla art-activists on her first visit, assesses the energy

In Bangkok’s Chinatown, among shophouses, street vendors and car workshops, can be found an unexpected addition to the neighbourhood: the newly opened Bangkok Kunsthalle. Settled in an old printing house that had been abandoned following a fire, the institution was established by art patron and philanthropist Marisa Chearavanont, wife of the chairman of Thailand’s largest agribusiness, CP Group, with Stefano Rabolli Pansera (formerly of commercial gallery Hauser & Wirth) as director. The newly opened institution devotes itself, as stated in its website, to promoting art, cinema, music, architecture and other creative endeavours.

Its first commissioned solo exhibition is Korakrit Arunanondchai’s immersive nostalgia for unity, on view through the end of October. Arunanondchai transformed the ruined printing house into a set for his work, leaving the main hall bare save for a yellow haze settling in the air. The ground looked scorched, and there was text with words like ‘after death’ embossed on it, supposedly a prayer written by the artist. The press release compared Arunanondchai’s ‘resurrection’ of the building through art to the allegory of the phoenix rising from ash. The artist is well known for his performances and videoworks: here it felt like we had walked onto a set, actors in trance, immersed in fog, under an unfolding movie he was directing. Associations kicked in immediately: the ambience of Blade Runner 2049 (2017); or a version of Olafur Eliasson’s Yellow corridor (1997), recently on view in that artist’s Your curious journey retrospective at Singapore Art Museum. It also struck me that the atmosphere bore a striking similarity to the pollution visible in Northern Thailand during haze season, from February to April.

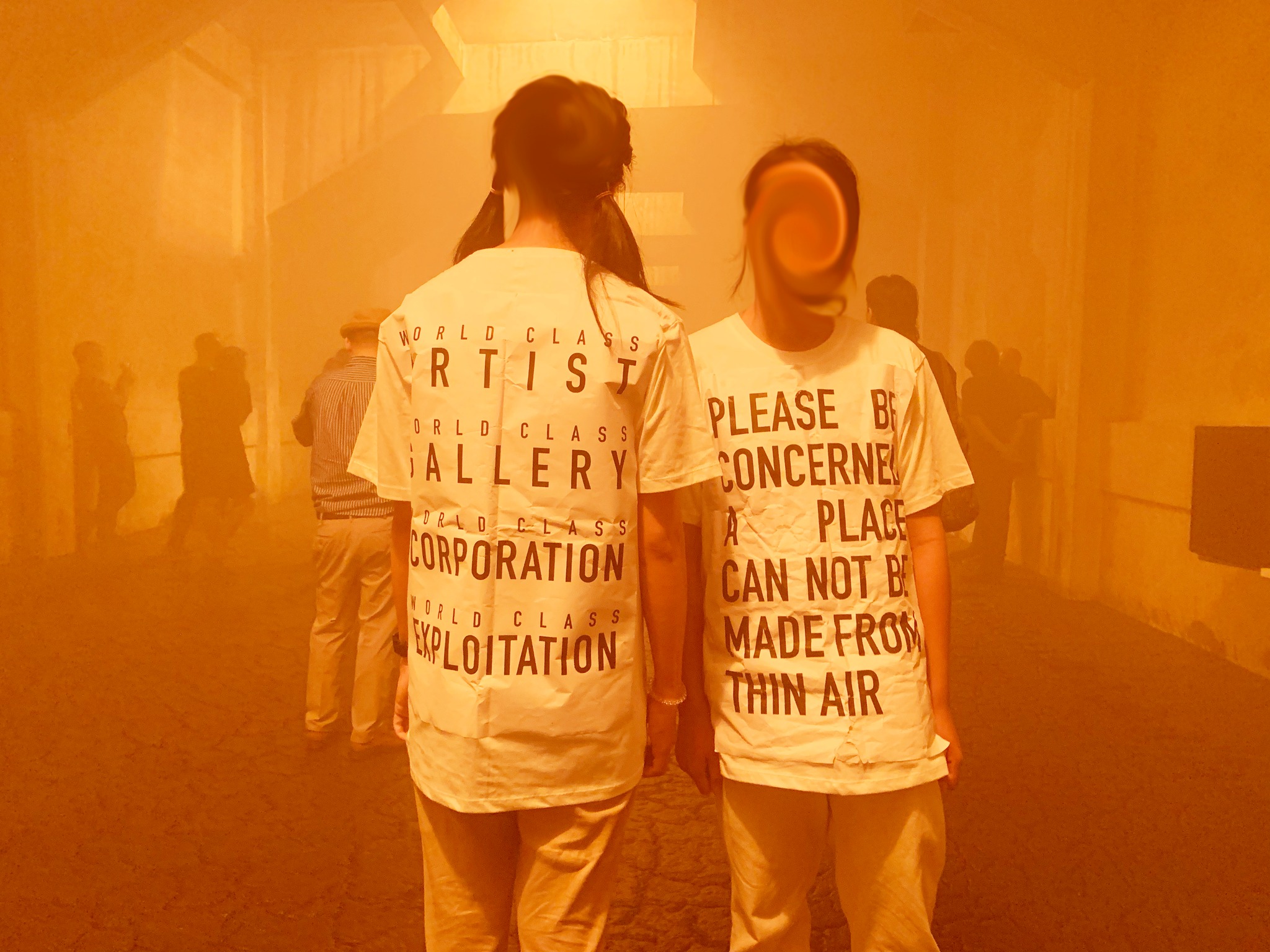

Two people suddenly emerged from the mist wearing T-shirts with slogans in all-caps: ‘A PLACE CAN NOT BE MADE FROM THIN AIR’, ‘WORLD CLASS ARTIST, WORLD CLASS GALLERY, WORLD CLASS CORPORATION, WORLD CLASS EXPLOITATION’ and ‘THIS COUNTRY IS YOUR GALLERY FOR EXHIBITING THE ART OF MONOPOLY’. Later I heard that this was a guerrilla performance by art-activist group artn’t, from Chiang Mai. When I called them to find out more about the performance, one of them told me that “the origins of art funding deserve critical examination”. Another added, “It’s as if the world is divided. Inside, there is fake dust from smoke machines. While outside, people are about to die because they can only breathe ashes.” Air pollution in Northern Thailand has been linked to feed-corn farming, as contract smallholder farmers clear land by burning, and their corn is sold to multinational agriculture corporations’ farms. Over the years, activists have put pressure on companies that benefit from the crop to take greater responsibility for the supply chain.

In an interview with Art Basel’s online editorial platform, Chearavanont spoke of how ‘one of (her) friends arrived at the opening in a very glamorous black lace dress but was confused as to where the kunsthalle was, assuming it would be a luxury venue. The kind owner of the noodle shop next door had to show her the way in!’ Her story points to a disconnect between the kunsthalle and its surroundings, no matter how much you try to separate what happens inside the kunsthalle from what is going on outside: after all, this is an art centre with a German name amid Thai-Chinese local businesses operating under the pressure of rising rents caused by gentrification.

Despite the uninvited performers, the exhibition was a success. Arunanondchai’s allegory of the phoenix’s rebirth mirrors the fate of the building as it transforms into a space for art and creativity, while distracting us from the reality we will soon face when dust season, beginning in November, reaches Bangkok.

Philanthropy is crucial in a country where government funding for the arts is limited. Yet concerns must be raised when an act of philanthropy may end up doing something else entirely. While it is undeniable that art and money often go hand in hand, is it naive to hope that the Bangkok Kunsthalle can start critical conversations about the issues of exploitation and environment? Will it become, as Arunanondchai’s exhibition positioned it, a sort of phoenix that can invigorate the art community of Bangkok and its discourses? It’s early days yet, and only time will tell.

Pearamon Tulavardhana is a writer based in Singapore and Bangkok