It’s time to revive the model of artist placements

While most of the artworld was distracted by the revolution of an (almost) all-female Venice Biennale, another art revolution kicked off on the other side of Europe. On 12 April, the Irish Government opened applications to their much-vaunted Basic Income for the Arts (BIA) pilot, a three-year scheme that will see weekly payments of €325 made to 2,000 randomly picked artists and creative freelancers. It stems from the explicit recognition in a government taskforce report that freelance creative workers often struggle to make a stable income from their work, forcing them to seek additional employment which ultimately detracts from their creative endeavours. The British visual arts sector is particularly pernicious, dominated by workers toiling for low or no pay, while a few big players clean up. In this ‘winner takes all’ economy, where only 7 percent of artists earn more than £20,000 per annum for their work, most make up the shortfall by juggling a portfolio of low paid and often precarious jobs. Even for those with a public profile, gallery representation and works in national collections, the inconsistent nature of the work can make a liveable income elusive.

If we want an inclusive art world open to artists from all backgrounds, we must reconsider the speculative model of art creation upon which the neoliberal art market is based. This sees the artist bearing the up-front costs of creating new work (studio rent, materials, life expenses – housing, bills, food etc) with no guarantee of a resulting sale, leaving most seeking paid work to underwrite their costs and/or ensure a stable income. Juggling two – even three – jobs might be possible for young, able-bodied artists, free from caring responsibilities, but it quickly becomes unsustainable and excludes aspiring artists without other sources of income (like long term savings, family wealth, or a supportive partner).

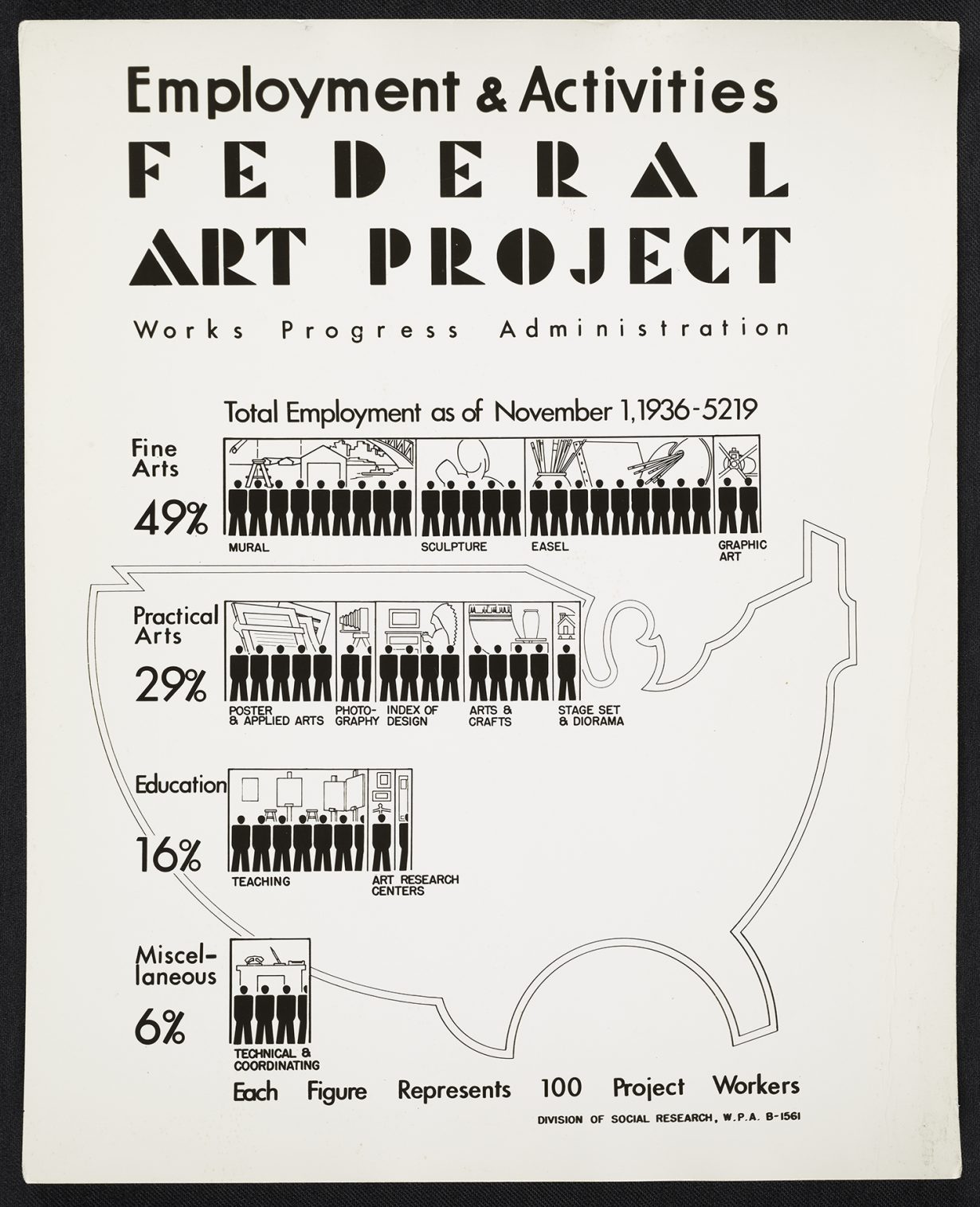

What might alternative modes of cultural production look like, that foster greater inclusion and overcome the inherent structural inequality of speculative art-making? One answer is to pay artists for their labour rather than for the potential value of their finished works. Beyond the Universal Basic Income model (or indeed BIA), another example is in Roosevelt’s New Deal, whose Federal Art Project (FAP, 1935-43) provided direct employment for around 10,000 artists to create posters, public murals and photojournalism. In exchange for a regular income, artists delivered a piece of work every six weeks, a process Jackson Pollock credited with allowing him eight years of paid employment during which to evolve the style of painting that later brought him such success.

What about artist placements? The idea of organisations hosting artists or offering residencies was a radical concept in the 1960s when it was conceived by the Artist Placement Group (APG), a London-based coalition of artists (launched in 1967 by Barbara Steveni, John Latham, Barry Flanagan, David Hall, Anna Ridley and Jeffrey Shaw). They sought to challenge the dominance of the art object and the studio as workplace by embedding artists into industry as ‘engineers in process’ – to challenge and facilitate conversations questioning norms of capitalist production. There was no predetermined outcome; for APG, as stated in their proposal, ‘the context [was] half the work’. British Labour politician Tony Benn was later so taken with the revolutionary potential for mutual benefit that he suggested they approach Barbara Castle, who was Secretary of State for Health and Social Services (DHSS) from 1974–1976, to explore opportunities for artists within her department. John Latham was placed with the Scottish Office (1975–1976) and Ian Breakwell at Broadmoor and Rampton Hospitals (within DHSS) in 1976.

A contemporary New Deal for the Arts could expand upon these precedents; obliging every government department, local council and private company or organisation with over 200 employees to offer a paid artist placement would be a start. Cornelia Parker’s 2017 stint as the official ‘Election artist’ even suggests that the concept might not be as unpalatable to the current government as we might assume.

Ring-fenced state and private sector support of the arts is already evident in some policy initiatives such as Stockholm’s ‘One Percent Rule’. Similar to the UK’s ‘Section 106 agreement’, but more specific, it stipulates that at least 1 percent of the budget for all new buildings in the city (new construction, conversion and extension) be allocated to publicly accessible art work. Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands operate similar percentage models to fund public art, offering several templates for international onlookers.

In the UK, a contemporary New Deal for the Arts was a central feature of the DACS (Design and Artists Copyright Society) Manifesto for Artists, published in 2021, which proposed ART WORKS, a nationwide pilot scheme of placements for up to 100 artists within local communities, who would be paid a living wage for a year-long programme of work. (It was an idea that, somewhat inevitably, never took off, instead morphing into the newly-proposed Smart Fund.) Integrating art into civil engineering projects at planning level would create visually and sensually engaging landscapes/cityscapes; local projects, employing skilled community artists to include workshops with schools and marginalised groups, would enhance societal engagement and cohesion, and even, perhaps, foster a greater sense of civic pride and placemaking. It would also, of course, put money directly into artists’ pockets without subsidising or mimicking the highly iniquitous neoliberal art market. With examples like the UK government’s declared, if concretely indiscernible, intention to ‘build back better’, a New Deal for the Arts would offer wide-ranging opportunities to the most excluded of artists, fulfilling the so-called ‘levelling up’ agenda whilst offering excellent value for the public purse.