An exhibition on marginalised labour reveals how the power to represent oneself matters more than simply being seen

In contemporary exhibition argot, ‘underrepresented’ has become something of a cliché. Making space for people who have historically been excluded from the rarefied world of galleries and museums is entirely worthwhile, but it can fall flat: box-ticking exercises that don’t seek to change the structure and practices of an institution come off hypocritical, while exhibitions that fail to properly consider the multiple meanings of ‘representation’ – which is, after all, literally their business – muddle our understanding of the issues at stake.

Many of the works in Hard Graft: Work, Health and Rights at the Wellcome Collection in London, which promises to explore ‘links between underrepresented work, the people who do it and where it takes place’, take a playful, politically spiky approach to the ambiguity of the term. In photojournalist Louise Rocabert’s series Women of Ibis Batignolles (2019-21), chambermaids from France’s former colonies in Africa who work in a high-volume Paris hotel are shown demonstrating while on strike over low pay, racism and sexual harassment. In one picture they dress as ghosts, white sheets draped over their heads. This is ‘representation’ several times over: an exploited and often ignored group of workers making a political demand, while creatively drawing attention to the way their labour is rendered invisible – be it by the workplace etiquette, unsociable hours, or direct discrimination. (It worked, too: the women won their long-fought strike in 2022.)

Given its theme – and its location in an exhibition space attached to a global health research charity – one might expect Hard Graft to tell a familiar story of liberal progress. Perhaps, for instance, how the trade union movement, combined with enlightened state reforms and advances in public health, made our workplaces healthier and happier. But Cindy Sissokho, an in-house curator at the Wellcome Collection (and cocurator of the French pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale), focuses for the most part on three specific types of work: forced labour during the era of the Transatlantic slave trade; sex work, historic and modern; and contemporary caring and cleaning.

On the face of it, ‘underrepresented’ seems a curious framing. The first two forms of work are heavily represented in visual culture, from Hollywood movies to fine art – there are more courtesans than clerks depicted in the national art museums of Europe, for instance. Even domestic work is a kind of popular shorthand to emphasise upstairs-downstairs class distinctions. The confusion is not helped by the exhibition’s thematic structure, which divides the exhibits into three spaces: the plantation, the street and the home. In the first, we find slavery and its legacy; the second, sex work and street sweeping; and the third, unpaid and underpaid housework and care work. The leap between the first room, bearing the horrors of chattel slavery, and the subsequent two – which deal with people who are certainly marginalised and exploited, but in strikingly different manner – is jarring.

There is a thread though, even if Hard Graft makes the connection less explicit than might be useful. Capitalism has always relied in part on the labour of people who are forced outside the bounds of ‘normal’ work. That might be via the extremes of slavery; or through the unpaid domestic work required to produce, feed and care for a ready supply of workers; or through stigma, racialisation and restrictive laws such as today’s immigration regimes, which keep a portion of the workforce sufficiently pliable. These are all also situations in which people have been denied, to varying degrees, the power to represent themselves – both in the sense of determining how they are seen by others, and of exerting control over their working conditions. Hard Graft aims to flip that logic on its head, celebrating the forms of resistance conjured up by people consigned to work in exploitative, often physically harmful circumstances.

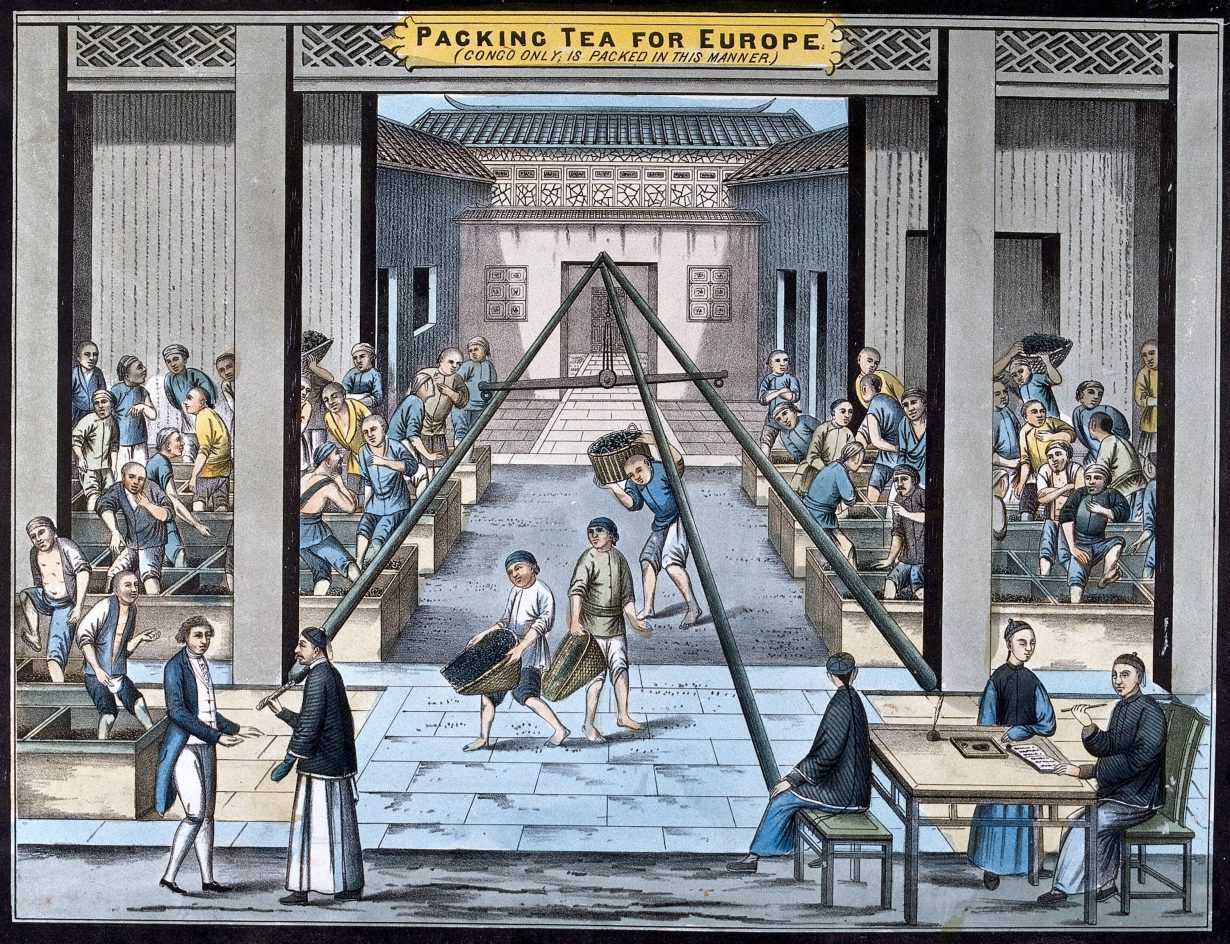

The ‘plantation’ section juxtaposes images showing the spatial logic of colonial-era extractive industries – enslaved labourers neatly spread out on a Brazilian coffee plantation in an 1882 photograph by Marc Fernez; the symmetrical, hierarchical assembly line of a British tea warehouse in China, in a nineteenth-century lithograph – with contemporary works that pay tribute to the way enslaved people tried to keep one another alive. A series of portraits from 2021 and 2023 by London-based artist Charmaine Watkiss, for instance, show women adorned with plants and tools associated with the ancestral herbal knowledge passed down through her family and by others uprooted from Africa to the Caribbean.

Healing is a key element of the second space, whose centrepiece is an installation by British sculptor Lindsey Mendick. Money Makes the World Go Round (2024) is a new commission inspired by two incidents in which sex workers occupied churches, in France and the UK respectively, to protest police harassment. A church wall, replete with stained glass windows, overlooks rows of small, brightly-coloured ceramic money boxes placed on pews. In the centre of the church wall is a screen, playing a video in which the Jamaican-British poet Mendez delivers a kind of sermon about the motivations for and the hazards of taking up sex work.

This is a subject the world treats most often with a mix of prurience and disgust – see, for instance, the nearby 1790 engraving of prostitutes in Bern, Switzerland collecting night soil as punishment for plying their trade. But Mendick’s installation reclaims the glitz and the gaudiness that accompanies conventional depictions of sex work to create a kind of private, celebratory space for people whose jobs lead them to be treated as public property. The sermon is based on the real testimonies of contemporary sex workers, gathered in collaboration with members of the SWARM activist collective: another demand by people who want to be seen and heard on their own terms. Lumpy and rough, the ceramic money boxes have the feel of homemade votive objects, perhaps brought by the imagined congregation.

What do we gain – and what do we lose – from this focus on marginalised forms of work? In general, Hard Graft opts for intimacy over the systemic view. There are some attempts at the latter, such as Forensic Architecture’s video study of environmental racism; the disproportionate effects of pollution on Black communities in Louisiana, which is in part a legacy of the plantation system. But the Wellcome Collection’s archives surely have more to say about the long-term and mass impacts of work on health – or indeed, the tension that has run through modern medicine between healing and population management. To what extent, for instance, has contemporary mental health treatment been shaped by the pressure to keep people in the workplace as opposed to tackling the social and economic conditions that might contribute to their illnesses? The exploitative potential of medicine is hinted at in the exhibition, for instance in a nineteenth-century medical manual by a British doctor containing ‘practical rules for the management and medical treatment of Negro slaves, in the sugar colonies’, but it feels like a fascinating and important story has been skated over.

Yet the intimate focus allows us to see and hear the people at the centre of this exhibition in a way that emphasises their own capacity – and by extension, ours – to resist systems that reduce us to cogs in a machine. After displays of vintage agitprop produced by the 1970s Wages for Housework campaign, disability rights campaigners and other radical initiatives focused on the domestic and caring spheres, Hard Graft concludes with London-based Vietnamese artist Moi Train’s Care Chains (2024). Inspired by the 23,000 people who migrate to the UK each year to work in private households, the piece is a multisensory room devoted to hands: touching one another in a wraparound animation on the wall; clapping, in a rhythmic, vibrating soundtrack; as silhouettes projected onto a table in the middle of the room. Based on the movements of 12 female domestic workers, one might expect this narrow visual focus to depersonalise its subject; instead it sharpens the viewer’s attention. What potential lies in the human body, it seems to ask – and to whose benefit does our society choose to direct it?

Hard Graft: Work, Health and Rights at Wellcome Collection, London, through 27 April 2025

Daniel Trilling is a journalist and author focusing on human rights and politics