Though It’s Dark, Still I Sing, curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, captures the sombre mood of Brazil in 2021, a country ravaged by the pandemic, environmental destruction and the excesses of its far-right administration

Uýra describes themself as a ‘hybrid entity’, part human, part of nature: in the 15 photographs that open the São Paulo Bienal, this quasi-mystical figure seems to merge with or perhaps be born of the landscapes in which they pose. In one, a single, blue, dilated eye peers out from a mass of straw hair, their body painted a deep ochre through which chest hair pokes; the ruddy palette blends with the excavated earth of the pit in which the artist stands. A digger can be seen in the background. In another, their skin now oily black, shells covering their eyes, Uýra stands in a heavily littered landscape, a beach of discarded plastic and chemical slime: an alien being, born of a polluted world, that is in itself not alien, simply ours, now.

The downbeat introduction to the exhibition continues: nearby, a giant meteorite sits on a plinth, one of the few objects left undamaged by the fire at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro in 2018, a moment of widespread mourning and anger in this country. The black surface of this extraterrestrial survivor is replicated in the dozens of monotypes by Carmela Gross on the wall behind, each a single sooty smudge – akin to an enlarged dirty fingerprint – titled Boca do Inferno (Hellmouth, 2020).

Curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti’s opening gambit captures the sombre mood of Brazil in 2021. The exhibition, Though It’s Dark, Still I Sing, which opens this weekend, was delayed a year as Brazil sleepwalked its way towards becoming one of the pandemic’s most rampant hotspots, a negligent far-right government leaving over half a million dead. Meanwhile fires rage through the Amazon – driven by deforestation carried out with the tacit approval of President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration; a new attack on indigenous land-rights is being orchestrated through the courts as I write; and inflation is going through the roof, leaving the always precarious working population floundering.

Even the arts, so often perceived as a bastion of optimism in a land that is frequently the locus of negative critique, are sullied in Visconti’s introductory picture: up the ramp to the first of the three further floors of the Oscar Niemeyer-designed Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion – home to the Bienal since 1957 – the visitor will find Ana Adamović’s My Country Is the Most Beautiful of All (2011–13), a film that reunites the members of a 1970s Yugoslavian choir to sing a song steeped in nationalism. The composition, which may have sounded sweet (if cynical) in the voices of children, feels grim when sung by wearied adults. Nearby is a series of ‘news reports’ made by Andrea Fraser for the 1998 Bienal, intended to be broadcast on Brazilian television, but never aired. With her trademark satire, the American artist interrogated the Bienal organisation itself through a series of pointed interviews with curator Paulo Herkenhoff and other such luminaries including Brazil’s then-culture minister. The latter waxes lyrical about the importance of corporate sponsorship, that back then extended to companies like Kodak being given concessions to sell their wares within the show itself.

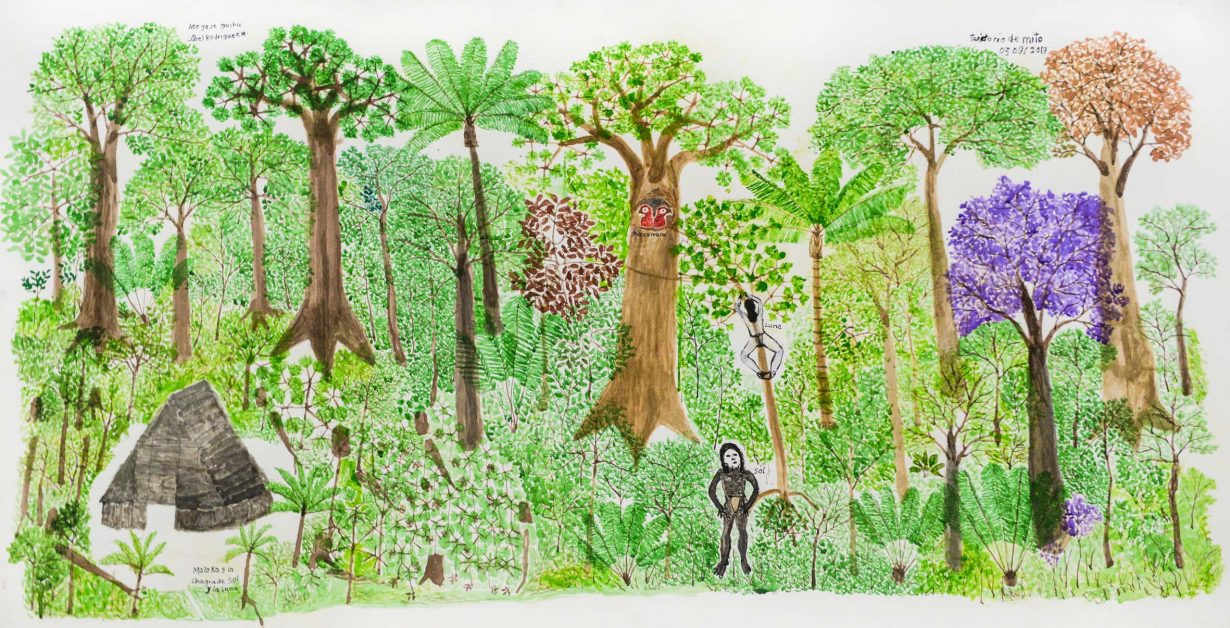

The inclusion of Fraser’s lost work is a pointed bit of institutional self-reflection by Visconti. As his show progresses, there unfolds a much needed recognition of Black and indigenous artmakers: in Carta ao Velho Mundo (Letter to the Old World, 2021) Macuxi artist and activist Jaider Esbell has written and drawn over a book of European art-history, denouncing the colonisation of indigenous lands; next to Lasar Segall’s brooding semi-cubist 1950s oil paintings of forests, and Lygia Pape’s Amazonias – neo-concretist red steel sculptures dating from the 1990s – is a series of four double-sided works by Daiara Tukano suspended from the gallery ceiling. On one side of each the artist – who belongs to the Yepá Mahsã people (also known as Tukano) – uses acrylic to depict birds sacred to her people; on the verso are bright abstract weavings using feathers. Likewise Sueli Maxakali has built an installation of dresses and masks dedicated to the Yãmiyhex, the spirit women in Maxakali cosmology. An exhibition highlight is the ink drawings of Abel Rodriguez, now based in Bogotá, who draws the flora and fauna of the Colombian Amazon from memory, in the Nonuya tradition of recording the natural world.

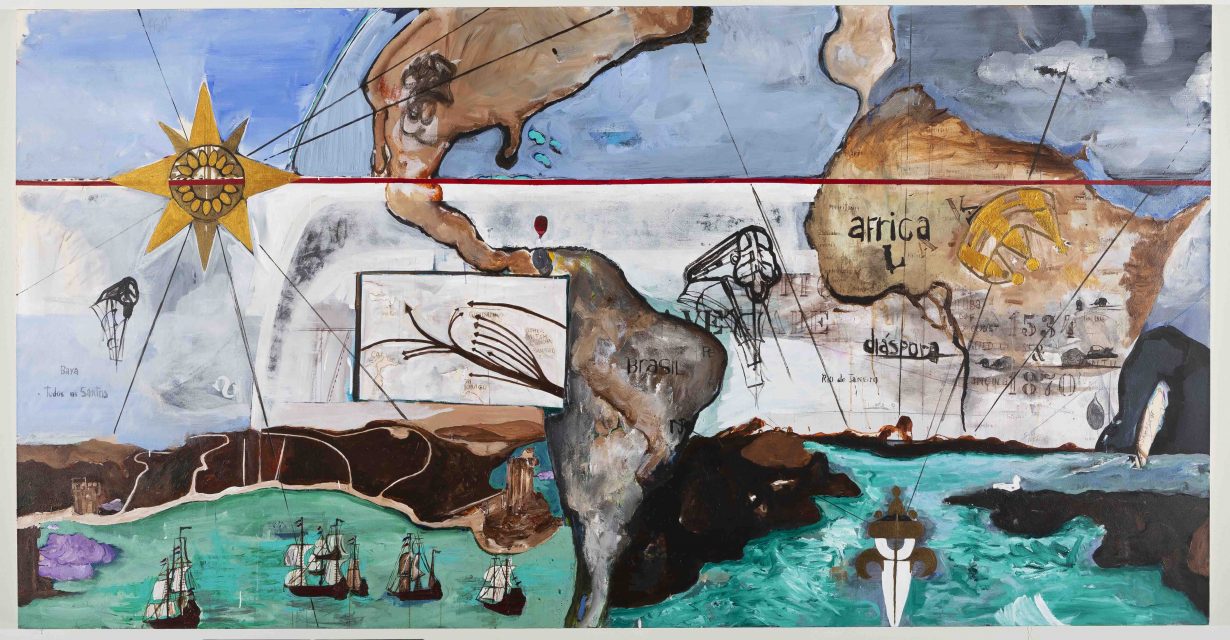

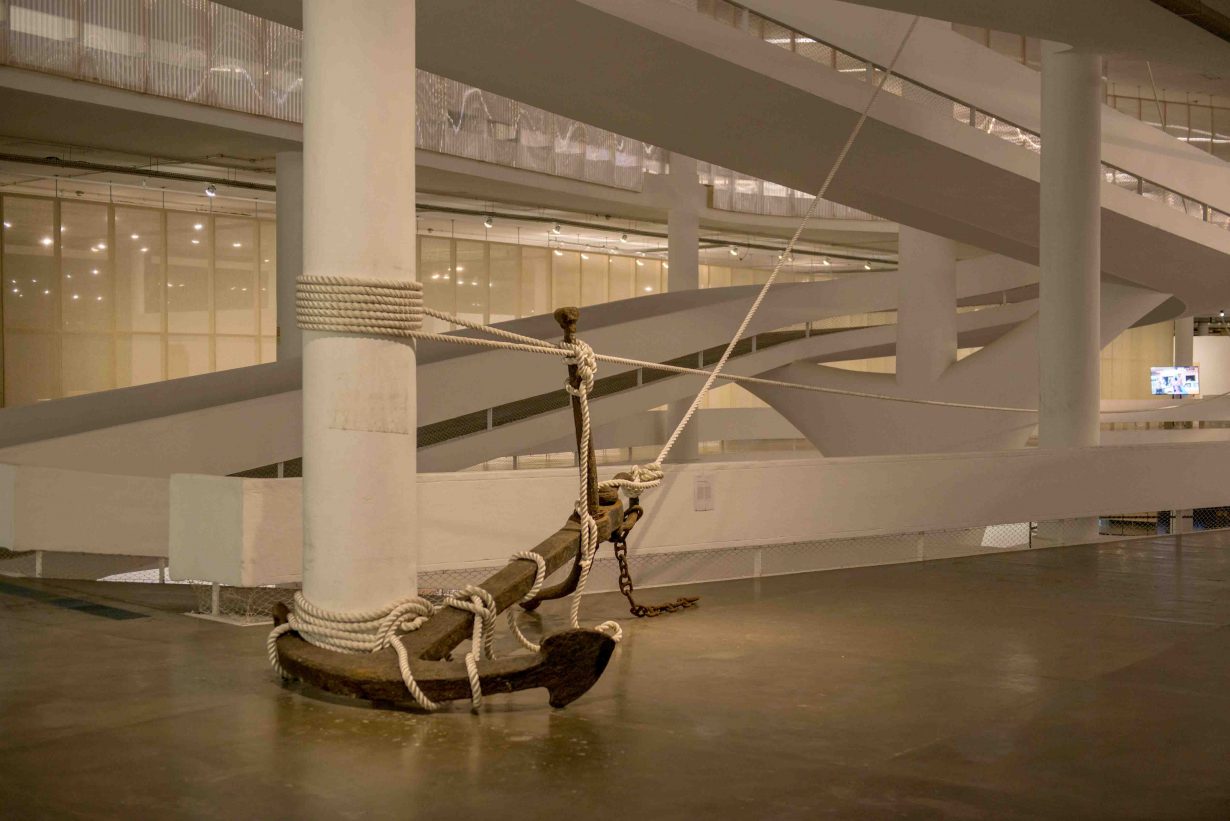

A series of collages by Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, the Jamaican dub pioneer who died just days before the exhibition’s opening, make reference to the transatlantic slave trade, as do the largescale paintings of Brazilian Arjan Martins, who also contributes an installation in which a thick rope is strung across the vast venue, tied around pillars, the two ends meeting at an anchor to form a triangle representing the trade route between the European and African continents and the Americas. As traumatic, but less bombastic, are two delicate embroideries by João Cândido, a Black Brazilian sailor jailed for denouncing the corporal punishment meted out to Black sailors in the navy, many of whom had been forced into service. One is dedicated to love, the other to freedom, their beauty at odds with the circumstances of their creation: made in prison around 1910 they recall the injustice that birthed Brazil and remains endemic within it today. In the context of such works that confront structural racism, past and present, Fraser’s inclusion suggests, even more emphatically, that Visconti (an Italy-born white male) recognises that the organisation that appointed him should also be the subject of critique. And for all the laudable anti-racism on show here, in 70 years the Bienal – the preeminent exhibition of a country in which white people account for less than half the population – has never been led by a Black or indigenous curator. Few women have been appointed to lead it either.

And yet, despite all this, Though It’s Dark, Still I Sing does provide some space for optimism. Indeed from its mournful beginning, an emotional journey cleverly unfolds as one proceeds up the pavilion’s ramps. Surrogates, a 2016 slide projection by American artist Amie Siegel depicts repairs made to European ancient and classical artifacts. Nearby is an exhibit of Tupiniquim earthenware, cooking objects the likes of which were swapped with Portuguese settlers in an attempt to preserve indigenous identity (and possibly stave off violence) and which went on to be appropriated into the colonial Ceramica Paulista style. That they are now being shown institutionally, and due credit is being made to the inspiration they provided, is itself a moment of social repair.

The last floor features many of the artists the visitor has previously encountered – Esbell again, Rodriguez, more phenomenal sculpture by Juraci Dórea, an artist who left his art objects alone, documenting their installation in photographs and texts, in the landscape of Brazil’s northeast, an environment that informed their making (often made of leather, they were prone to be found and disassembled by locals to patch up hats and clothes). A gesture, perhaps, towards the cyclical nature of history. The penultimate work to be encountered is Towards The New Baroque of Voices (2021) by Manthia Diawara, a series of video interviews with radical, emancipatory, anti-colonial activists and thinkers (including Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka and Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o). Spilling through is an optimistic, beautiful piano score, the soundtrack to Two Choirs (2013), a second work by Adamović: this time it’s a group of deaf children signing the song. Where the show started in horror, it ends in beauty. There will always be bad times, all we can do is try to make amends.

34th Bienal de São Paulo, Though It’s Dark, Still I Sing, Fundação Bienal, São Paulo, 4 September – 5 December 2021