Over the past 50 years, is there anyone who’s written with more breadth, cogency and conviviality about the intersection of art and politics?

A few years ago, mid-performance at London’s Wigmore Hall, the raconteur pianist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet stood up to say that the flowing nature of Debussy’s music gave him the impression that he composed as he played. Thought and composition are one. T.J. Clark’s prose shares a similar directness and spontaneity. Over the past 50 years, is there anyone who’s written with more breadth and cogency – yet with such a convivial tone – about the intersection of art and politics? About the inexhaustibility of modernity, the endless wonders of painting? Those Passions is a compendium of essays written between 1997 and 2023, covering everything from Hieronymus Bosch to ‘screen capitalism’. If Bosch’s work is political because his ‘Christian nihilism’ offers none of the consolatory isms of modernity, ‘screen capitalism’ collapses time, offering a feeling of constant ‘atrocity’.

In his review of the 2016 James Ensor exhibition at London’s Royal Academy, he writes, ‘I couldn’t shake off the memory’ of a passage from Dostoevsky’s novella The Eternal Husband (1870), which he happened to be reading at the time. Quoting a long section that describes Velchaninov’s dream, in which he beats the shit out of a mute accuser, Clark writes, ‘I think this gets us into Ensor’s world.’ While in his essay on Velázquez’s portraits of Aesop (1636–38) and Mars (c. 1638), he writes, ‘I cannot look long’ at these figures without thinking of a rifleman in the same artist’s Surrender of Breda (1635), which then can’t help but remind him of a fragment of Brecht. He reveals to the reader a chain of associations and ideas, nimbly committing them to print along the way. ‘You will have to forgive me’, he writes in ‘Beauty Lacks Strength: Hegel on the Art of his Century’, before confessing that he sees Hegel’s ghost in a blue shawl sitting loosely on a table in Matisse’s painting Les tapis rouges (1906). What makes Clark’s writing effective, and a pleasure to read, is how he permits himself to follow any association or insight he has along the way. His method preserves a sense of fluid subjectivity – and, by extension, honours the reader’s. Thought and writing are one.

A steadfast leftist – ‘By “left”’, he writes in ‘For a Left with No Future’, ‘I mean a root and branch opposition to capitalism’ – Clark’s method works hand in hand with his politics. In his introduction, he writes that capitalism ‘remains one great root of our evils’, not least in its capacity to paralyse political discourse. Hence the crucial importance of unifying thought and perception in the way he writes. In his essay on Guernica (1937), he surmises that Picasso loved a fable for the way ‘it recognizes that alarm and misrecognition are at the very root of perception’. If perception is consciousness, to be conscious in the present day is to perceive monsters, because ‘there is always too much guilt and horror to go round’, as Clark writes about Ensor’s suffering – ‘and that’s what art ought to register’. Opposing capitalism, for Clark, seems to demand more than brute resistance, invoking instead a social and aesthetic realm of dialogue, humour, tenderness and – a word that appears often in the book – humanity. Bosch, Velázquez and Ensor all provide ‘laughter from the left’, while Delacroix’s treatment of violence is praised for its ‘strangeness and humanity’. The roving way he writes embodies these anti-capitalist values – and yet his essays are equally girded by discipline, avidity and expertise.

The week before Trump’s second inauguration, the London Review of Books published Clark’s ‘A Brief Guide to Trump and the Spectacle’. My first thought was: there’s no way this will be brief. My second: this should be fun to read. Clark’s ‘Brief Guide’ to Trump lived up to its name – short (relatively), sharp, a call for not ‘derision but tactics’. If ‘politics came to play the role that religion had played previously’, as Clark writes in his introduction to the book, the American president is the apotheosis of the false idol, a relentless spectacle of jackass machismo. Clark, with his generous prose, is chipping away at that flimsy image.

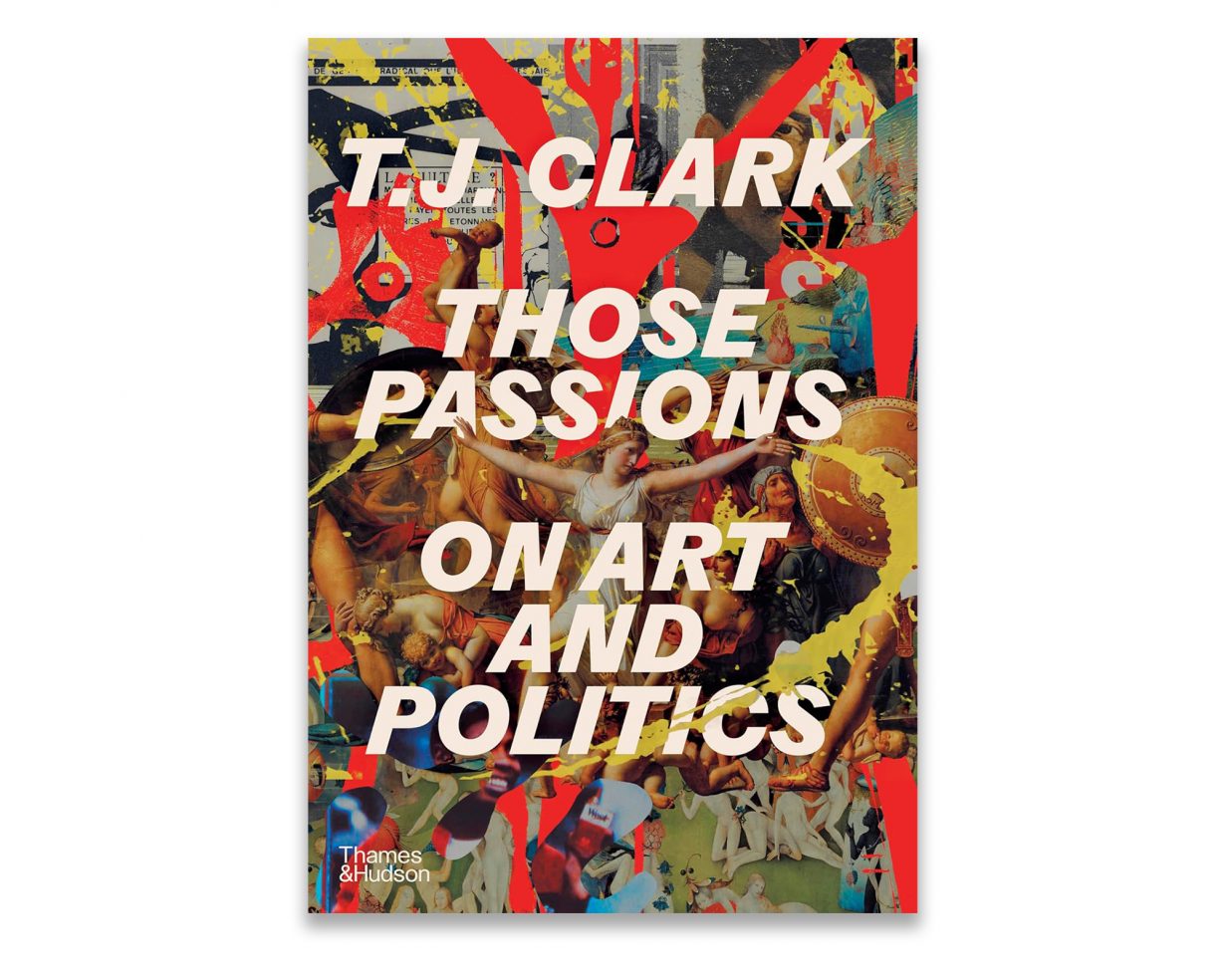

Those Passions: On Art and Politics by T.J. Clark. Thames & Hudson, £40 (hardcover)