ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists and curators exhibiting in and curating the various national pavilions of the 2022 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the leadup to and during the Venice Biennale, which runs from 23 April to 27 November.

ArtReview What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

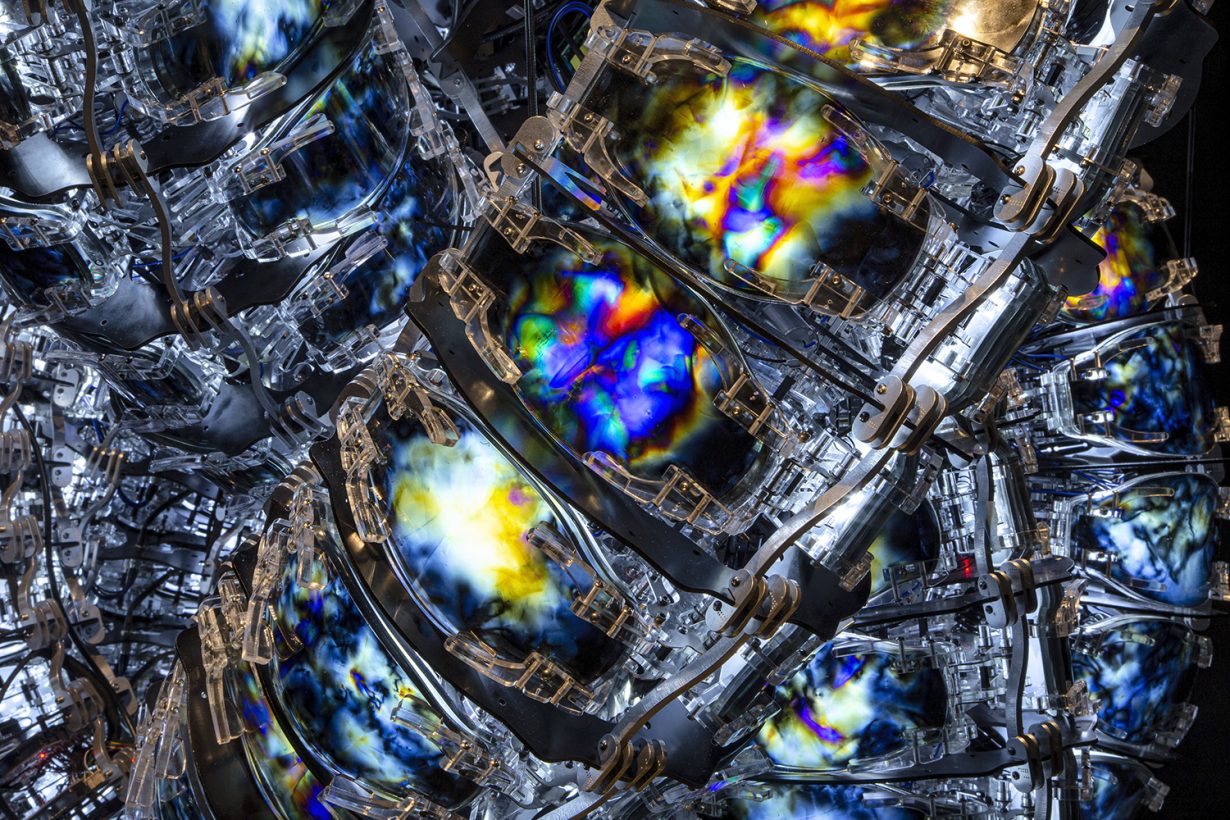

Yunchul Kim Together with the curatorial team and my production team Studio Locus Solus, the Korean Pavilion will present a series of interconnected ‘pataphysical’ installations, powered by imperceptible matter (muon particles) from outer space. I consider my artworks as living beings – bodies that are intra-acting (a Baradian term) and self-organising like the resurrected ‘actors’ from Raymond Roussel’s surrealist novel Locus Solus. I imagined the pavilion as a reflection of our world as a labyrinth – a de-centralised world – where everything is in entanglement with each other. These installations are a result of long laborious experimentations with various materials that took months of research until they came to life. At the foundation of my installations are my drawings. I often have dreams about strange creatures and swirling movement of things that I sketch out on paper. The installations all have a reference to earlier drawings that I have made, even going back to a sketch I made over 10 years ago after dreaming about a labyrinth filled with lion flowers, snakes and flare-like fluids. The exhibition will invite people to enter the world of materials where objects, beings, and nature all co-exist on an equal footing – imagining a flat ontology.

AR Why is the Venice Biennale still important?

YK The national pavilion exhibitions are what make the Venice Biennale unique and interesting. It does have a tendency to create clear borders between countries but at the same time it allows different cultures to come together – different from other biennials where a curator or a group of curators select a list of artists. It’s an arena that brings together diverse voices and stories from all around the world. We live in a hybrid world; a world of labyrinth; a world of entanglement, and what we are increasingly seeing with the national pavilion exhibitions at Venice are blurred borders, with different cultures ‘knotting’ together. Despite the wars and political tensions that we face, the Biennale provides a ground for exchange and solidarity in the name of art. We will see this more prominently this year, including our colleagues at the Croatian pavilion whose project is largely shaped by their exchange with other pavilions. We are also working to create collaborative moments with the Croatian pavilion and the Icelandic pavilion, and through our exchange we hope to make a wider hybrid event together.

AR Do you think there is such a thing as national art? Or is all art universal?

YK Art is universal. Especially in the context of Contemporary art (capital C), in a globalised and interconnected world today, the concept is troubled. I studied in Berlin and lived there until 2014. My artistic practice inevitably reflects my diasporic experience and the conversations I had with fellow artists and transdisciplinary researchers who I met throughout my career in Europe. My works are primarily based on my interest in matter and the world of materials, which are not confined to a nation concept. Having said that, my practice is transdisciplinary and is inspired by the traditional beliefs in Korea and East Asia. One of the key three key themes of Gyre is 신경 (sin-gyeong), which has double meanings – in traditional Chinese characters it means Path of Gods and also literally translates to ‘nerves’ in Korean. In traditional East Asian imaginary, the body is a universe, and the human body is a connector between heaven and earth. But this understanding of the Earth and heaven connected through the human body is not unique to Korea and East Asian culture and can be found in various civilisations around the world including the Siberian Shamans. Art reflects the multiplicity of identities, a cross-pollination of different cultures and expression of personal experiences of individuals, and in that sense it is hard to define or categorise what ‘national art’ means.

AR Which other artists from your country have influenced or inspired you?

YK Hakkyung Cha, the American novelist and artist of South Korean origin, has been an inspirational figure in shaping my practice. She emigrated to the US in the 60s when she was 11 and had a very tragic end to her life, ending her career short. Having experienced immigration as a ‘linguistic expulsion’, language was a key aspect of her works. She experimented with various artistic mediums including literature, performance, video, while subject to the pain of diaspora, separation from the motherland and difficulties of language communication. Her statement ‘looking for the roots of language before it is born on the tip of the tongue’ resonates in my practice – like the fluctuation of things in my imagination that has not yet been materialised, or materials that do not have any meanings or function attached.

AR How does having a pavilion in Venice make a difference to the art scene in your country?

YK Since Nam June Paik won the Golden Lion award for his participation at the German pavilion in 1993, he helped to establish a permanent pavilion for Korea, which opened in the Giardini in 1995. The presence of Korean artists in the international art scene has definitely changed since the 90s, and I’m sure having a pavilion in Venice plays a part in giving Korean artists a stronger international presence. Many of the artists who participated so far have a very successful career today, but conversely, I’m not sure if having a pavilion in Venice makes a difference to the art scene in Korea – it definitely makes it very competitive amongst curators and artists to get this opportunity.

AR If you’ve been to the biennale before, what’s your earliest or best memory from Venice?

YK The best and the last memory is the main exhibition at the 2019 Biennale: May You Live in Interesting Times curated by Ralph Rugoff. The concept of the fictional ancient Chinese curse used in the West to reflect the times of uncertainty, crisis and turmoil in the West, seems to be always relevant in our lives – there is always an element of uncertainty and crisis. A diverse range of artists, works, themes permeated that exhibition, which truly reflected our world as a labyrinth.

AR What else are you looking forward to seeing?

YK I am looking forward to all the exhibitions at the Venice Biennale this year and especially the main Biennale exhibition The Milk of Dreams curated by Cecilia Alemani. But most importantly, I am looking forward to reuniting with fellow artists, curators, and friends whom I could not meet for the last two years. It will really be a big moment for all of us as we approach a ‘new’ era after two years of lockdowns.

The 59th Venice Biennale runs 23 April – 27 November