Delving into the so-called Golden Age of Dutch art, Benjamin Moser’s The Upside-Down World is a treatise on artistic and worldly ambition

Benjamin Moser intended to write a history of the so-called Golden Age of Dutch art: the period during the seventeenth century when the Dutch empire was at its most powerful. He would sketch out the lives and work of preeminent figures, such as Rembrandt, Vermeer and Hals, alongside those less well known, roughly in mimicry of The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, the sixteenth-century work by Italian Giorgio Vasari, commonly cited as the first art historian. This was always going to be a fan’s guide, however, not an academic treatise. Moser would take the reader by the hand and, in a prose that slides between the elegiac and the chummy, point out the books he’d read, the paintings he’d seen and the museums he’d gone to as he discovered his subject. For Moser, who is American and had arrived in the Netherlands (for love) at the age of twenty-five, this immersion in art, he writes, was him ‘trying to find his footing in a new country’.

This is that book; but something else too. While many an art historian has delved into the private lives of artists for the purposes of adding colour to the criticism (from Vasari onwards), Moser’s book is a treatise on ambition. Artistic, yes; but worldly too. ‘How much political skill, how much backroom manoeuvring, is involved in an artist’s success?’ he asks. ‘The talent for moving in society is the dirty secret of many artistic careers,’ he states, and it’s as much true of artists today as it is of those from the past. The secret is ‘dirty’, of course, because no artist wants to come across as materialistically minded. Moser makes an example of Gerard ter Borch, ‘a middle-class boy from Zwolle’ with an ease for glad-handing who, on arriving in London, ‘quickly, and as usual, rose to high positions’. Compare this to ter Borch’s father, a man with similar artistic ambitions, but who never left the northeast Netherlands and worked in the tax office for 40 years. Then there’s Rembrandt, whose early success waned as he insisted on painting darkness and the everyday, not the elevated beauty patrons wanted. Compare his trajectory to that of painters Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck, who energetically changed their style to match the fashions of the day and consequently died rich and seemingly contented. Two hundred years after their deaths, however, measured next to Rembrandt, the pair were dismissed by critic Louis Viardot as ‘simple satellites, lost in the rays of the central luminary’.

Moser and his own career trajectory also come into focus. He is no slouch, with two biographies under his belt, one of the Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector, whose work he has also helped translate from Portuguese to English (and who died poor), a second of American theorist Susan Sontag (a consummate social climber among New York’s intelligentsia). For the latter he won the Pulitzer Prize, and there’s a sense that this level of recognition, and the pushback that sometimes comes with it (in the award’s wake, Moser received criticism from a fellow Portuguese translator and other Lispector biographers over acknowledgement) has spurred self-reflection.

He realises this is a risky venture: ‘any intrusion of the biographer will be quickly whacked down by chastising reviewers’. But it allows him to ask what catalyses people to write (or make art), and to write (or make art) the way they do. The answers are myriad, of course. And Moser is careful never to let his own ambition off the hook. There’s a hunger for wealth and privilege, like Flinck and Bol; there are those who are restless and obsessive in their creativity, like Paulus Potter and his endless paintings of cows; but then there are those – most of us engaged in such creative professions, really – for whom making art and making a name for oneself (why haven’t I won the Pulitzer!) are endlessly entangled: a helpless zeal to be seen and applauded. Does such ambition ever get sated? There’s something melancholic about this and the book Moser ended up writing; a shadow over the prose as dark as a Rembrandt, and as good in its gloom for it.

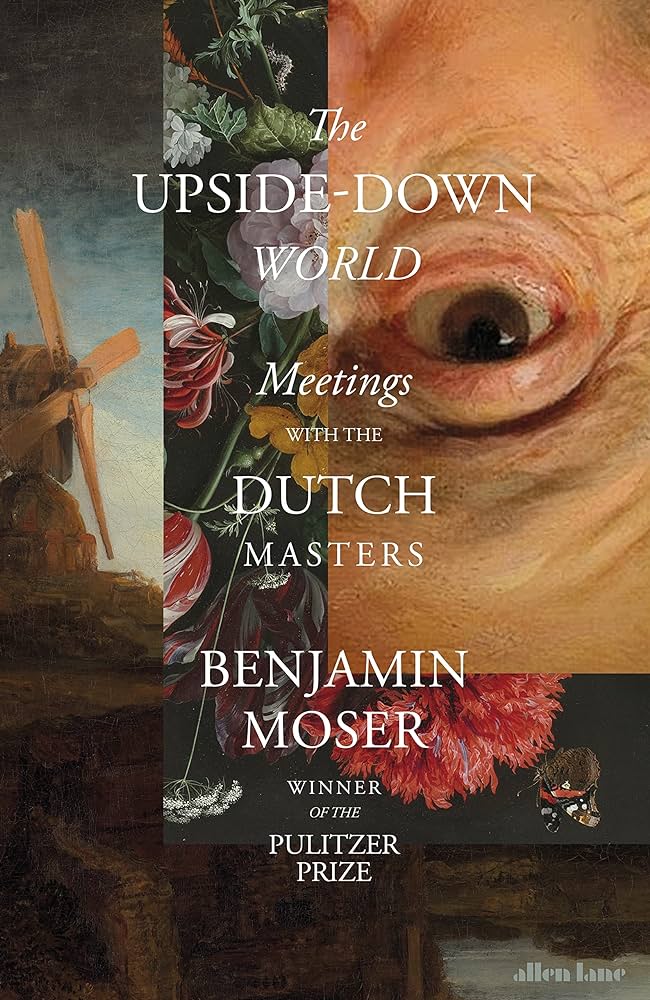

The Upside-Down World: Meetings with the Dutch Masters by Benjamin Moser. Allen Lane, £30 (hardcover)