The Time is Always Now at the National Portrait Gallery, London surveys the ‘Black Figure’ as both a genre and critical concept

Though it’s a standalone exhibition, The Time is Always Now makes its point all the more sharply if you visit the National Portrait Gallery’s permanent collection on the floors above. There you’ll find a history of portraits of the British and of portraits made by British artists. Gallery after gallery of paintings of eminent, mostly white, people: pallid, inscrutable Tudor nobility; chubby, pinkish and powdered Georgians; dashing, tousle-haired Romantics and free-thinkers of the Enlightenment; through to arrogant, moustachioed Victorian military officers, reclining on settees, maps of the British Empire on the walls behind them. Black people don’t make it into this history of British portraiture until much later.

With this in the institutional background, the present show surveys a more recent history of the painting of the ‘Black Figure’ (alongside a scattering of sculptural works), as curator Ekow Eshun frames it: an acknowledgement that it exists here both as a genre and a critical concept lodged within the wider discourses of Blackness. What we get are 22 artists, mostly from America and Britain, who have come to prominence over the course of the last two decades and whose work, as Eshun writes in his catalogue introduction, invites ‘a shift in perspective from “looking at” the Black figure via an external, objectifying gaze to “seeing through” the eyes of Black artists and the figures they depict’.

The show itself is divided into three loose thematic sections with the unsteady question of the subject’s position – of who is looking and who is painted, and what their relationship to the politics of ‘Blackness’ is – running through it. ‘Double Consciousness’ riffs on W. E. B. Dubois’s famous reflection on living as a Black person in a white society, as being a matter of a ‘peculiar sensation… this sense of always looking at oneself through the eyes of others’. In this section, painting becomes the vehicle for ironic criticism of the overdetermined meaning of ‘Black’, epitomised by Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Painter) (2009), whose female protagonist, painter’s palette in hand, smiles enigmatically at us as she works on a ‘paint by numbers’ version of herself. That her skin is chromatically black throws the semantics of being ‘seen as Black’ into crisis, since no skin in reality is this black. Marshall’s paintings open the door to less satirical negations of painterly naturalism: in Toyin Ojih Odutola’s grandiose portraits of glamourous, fashionable subjects whose skin is rendered in dense, nervous workings of pencil and charcoal, against the otherwise bright pastels of clothes and their opulent surroundings. Amy Sherald’s use of shades-of-grey for skin tones, against the posterlike hues and graphic clarity of her female subjects’ attire, make a different retort to ‘colour-blindness’. There’s something profoundly poised, gentle and unostentatious about Sherald’s depictions, such as the young woman of She was learning to love moments, to love moments for themselves (2017), her stance contrapposto, one forearm hitched up, hand around the back of her neck, a deft nod to the humanism of Michelangelo’s David (1501–04). But then, Sherald seems to suggest, all of painting’s history is the painter’s birthright – as with the flattened shading of the woman’s blue dress in A Midsummer Afternoon Dream (2020), with echoes of Poussin’s neoclassicism.

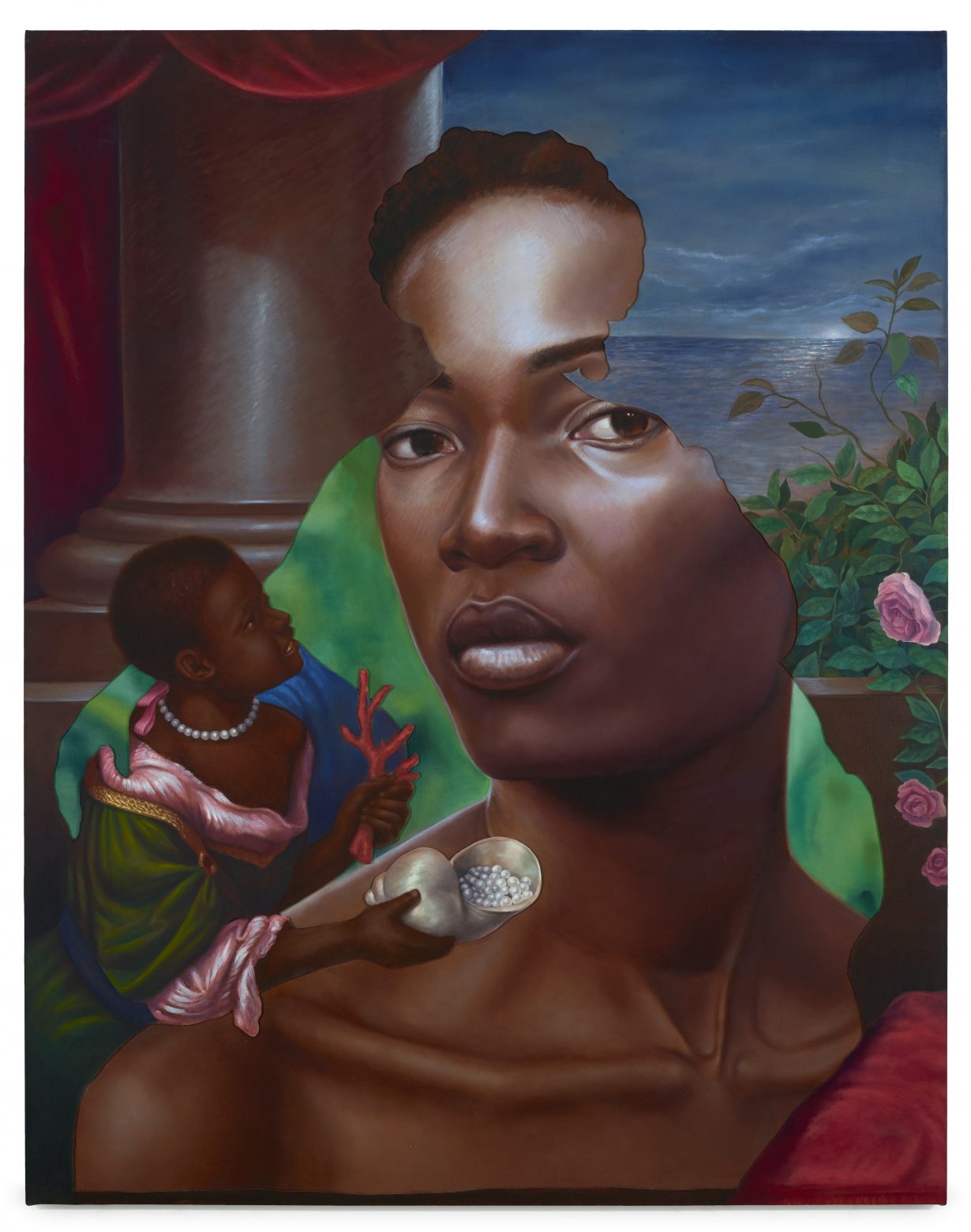

In the section ‘Past and Presence’ these utopian reclamations of art history rub up against a more sceptical dismantling of European painting, full as it is of the imaginary forms of colonialism and racism. Titus Kaphar’s surrealistic reworkings of eighteenth-century portraits (Seeing Through Time, 2018, and Seeing Through Time 2, 2019), in which (we assume) white aristocratic women, attended to by a Black servant, are redacted, cut out and replaced by a larger portrait of a young Black women staring out to us, implode the relations of racial visibility and invisibility in their uncanny rewiring of historical genre. A similar rhetoric is at work in Barbara Walker’s Vanishing Point drawings, which erase the white figures from Old Master paintings in order to high-lighting the previously ignored Black figures lurking in the background. Vanishing Point 24 (Mignard) (2021) shares its source with Kaphar’s Seeing Through Time 2: Baroque painter Pierre Mignard’s Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth with an unknown female attendant (1682), which, it turns out, hangs upstairs in the permanent collection.

But though these ripostes to Eurocentric history are necessary, they return the gaze of a society and a culture itself profoundly changed, so that even amid the currently charged politics of race and representation, some progress must have been achieved. This show would not be here if this wasn’t so. It’s perhaps why some of these works come up against a limit, dependent, despite themselves, on what they aim to critique. By contrast, the richest and most generative paintings here are the ones whose subjects look away from us, their viewers, and where the possibilities of painting as a medium are privileged: in Michael Armitage’s sensuous, tenebrous canvases, a contemporary world of political and personal events is condensed into almost psychedelic mythical scenes, such as in the strange world of Conjestina (2017). Here, the stocky figure, naked but for her boxing gloves – a reference to Kenyan boxer Conjestina Achieng – appears haunted by monsters. Jennifer Packer’s fevered colour and vaporous brushwork conjures subjects lost in thought, or sleep. Any thoughts that they, or we (who are we, after all?) might have about the significance of race dissolve into the singular presence of Packer’s subjects and the intimacy of their individuality.

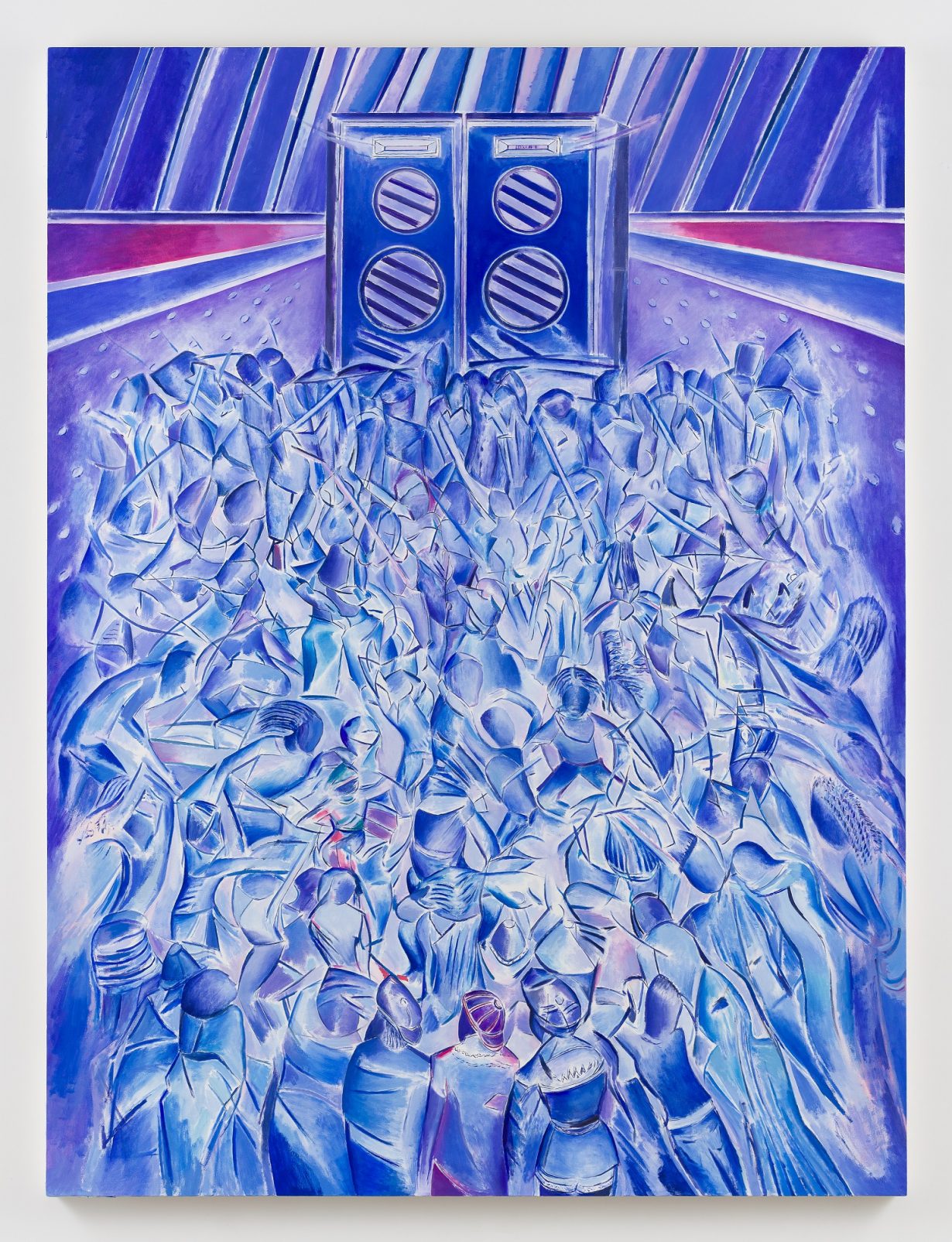

As novelist Esi Edugyan notes in her text for the catalogue, ‘the people depicted are – or were – living, breathing beings, not ideas or points to be made or repositories of collective anxieties’. And yet the collective experience of Black people, as with many other social groups, is still a reality. Here it is rendered in Denzil Forrester’s standout canvas Itchin & Scratchin (2019), which depicts a mass of faceless clubbers as a crystalline shimmer of cubistic, futurist sapphire blues and amethyst purples, the mass dancing before the totemic speaker stacks of a sound system. It’s a transcendent vision of community, rooted in the particularity of London and Jamaican nightclubs. Uniquely in The Time is Always Now, Blackness or whiteness don’t figure. Or it could be a future in which such differences no longer signify, or we no longer notice.

The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure at National Portrait Gallery, London, through 19 May