“My old friend Leigh Bowery would ask: ‘Where is the poison?’ And that’s a question I keep asking myself”

Cerith Wyn Evans and London’s Institute of Contemporary Art go back a long way. This is where, in 1975, as a seventeen-year-old schoolboy visiting London from Wales, Wyn Evans saw an exhibition by Marcel Broodthaers: plants, firearms, and garden furniture accompanying a screening of the Belgian artist’s film La Bataille de Waterloo, the latter focusing on a rehearsal for Trooping the Colour. This ambivalent concatenation of effects profoundly influenced the course of his art, and thus his life. (As Wyn Evans told Hans Ulrich Obrist in a 2002 interview, “I felt I had discovered something very exhilarating… this work was somehow forbidden, unsanctioned, not allowed. It seemed very stimulating that the pieces didn’t add up, that there was room to move, or if there were connections, there were weak connections.” ) Six years later, in 1981, having studied film at St Martin’s and made works that drew on his experience of Broodthaers’s art, Wyn Evans was an exhibitor at the ICA; he’d impressed then-director Archie Tait with his degree show. And now, when the time has come for his first exhibition in a British public space, he is there again.

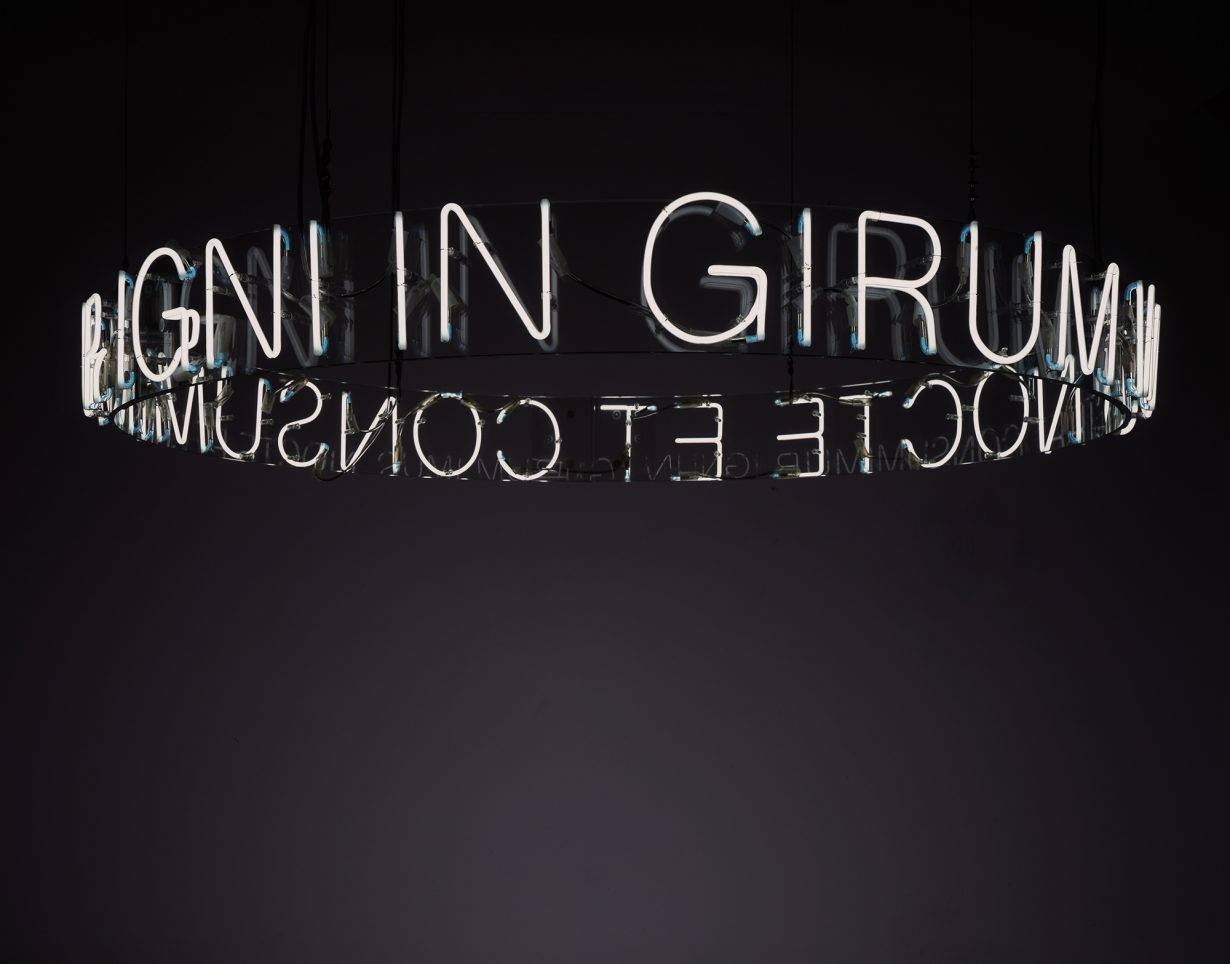

In the quarter-century between his two exhibitions at the storied venue, Wyn Evans has gone from being an experimental filmmaker to a respected visual artist, if not exactly ever a known quantity. His artworks problematise the flow of meaning from maker to audience: they are not only fairly open-ended but also variously employ restriction, encryption and obstruction. They have often involved language. A phrase by one of Wyn Evans’s personal pantheon of artists, writers and cineastes (among them Kenneth Anger, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Raymond Williams, and the eighteenth century Welsh cleric Ellis Wynne) may be spelt out fleetingly in fireworks, or beamed into the sky in Morse code by a Second World War searchlight. Or, as in one work using the poetry of William Blake, projected onto a spinning glitter-ball that bounces it back onto the gallery walls in splintered and unreadable fragments. Sometimes a multiplicity of texts will be combined, creating an open-ended polyphony allowing for collisions of meaning. At other times Wyn Evans privileges the viewer’s subjectivity by resurrecting visionary portals such as Brion Gysin’s hallucination-inducing ‘Dreamachines’.

But the ICA exhibition will probably feature none of this. In keeping with his tendency to mutate his art’s appearance every few years so as to avoid overfamiliarity, categorisation and consumption, Wyn Evans’s proposed work is denuded of both language and objects. And, indeed, pretty much everything else. “The plan is essentially – and I know it sounds terrible – to subvert by taking things out,” he says. “I’d like to take out a wall, the one in the downstairs gallery that is onto the Mall, and which has been there for about 70 years.” The galleries themselves, he anticipates, will be entirely empty. “It’s about doing less than as little as possible, which is quite hard to do. There’s quite a lot of work to do in terms of doing something that is really reductive in that kind of way.”

Although there are no direct quotations in this work, given the projected notion of the evacuated institution and the yawning hole in its frontage, names from the first and second waves of Conceptualism come to mind: Michael Asher and Gordon Matta-Clark, for instance. One thinks of Broodthaers again, of his film interjecting the local into his ICA show. But to place something fully in a historical continuum is a way of mummifying it, reducing it to commentary and to language. This is antithetical to Wyn Evans’s conception of art’s role, which is closer to that of a weapon. “I really want to hurt people by making this show,” he says. “I want to contaminate. I don’t want it to be generous at all. I really want it to kill people.” Wyn Evans, who describes himself as “fucking furious” about the trivialisation of the conversation around culture and its potential, tells me he has been reading Roland Barthes’s The Neutral (2005), in which the French writer, lecturing in 1978, near the end of his life, theorises the eponymous category as “everything that baffles the paradigm”. It is a sound prismatic through which to view the Welshman’s oppositional practice, of which Wyn Evans feels the best thing that has ever been written is a line by the art historian Mark Cousins, which described his experiencing his art as akin to being a deaf man staring at a radio.

By contrast, the worst thing you could do with one of Wyn Evans’s artworks is to ask what it means. Such would be to destroy the space of opportunity, the occasion for a slippage of meanings that it creates. The flipside of this is that, since there is no ‘solution’, his art regularly retains a vital strength through remaining a problem, a cyanide-tipped thorn. “My old friend Leigh Bowery would ask: ‘Where is the poison?’ And that’s a question I keep asking myself,” says Wyn Evans. “The poison, that is, as a way of somehow questioning democracy… and how it counteracts our processes of being in the world.” So there should be a hole in the Mall this autumn, and beyond it an empty gallery. (Although perhaps not; when I ask ICA curator Jens Hoffmann about it, he says there will be “other things”.) Something is opened up; simultaneously, something is closed down. Audiences are freed from the pressure of decoding artworks but left to fathom the import of an architectural negation.

Here is a straw to grasp, then, although Wyn Evans says it is not at the heart of the work. It has long been noted that there is an erotic dimension to his art: a subtext of deviance, if you like, inhabits his encrypted works in particular. “I’m increasingly interested,” he says, “in some kind of notion of pornography and exposure. I’ve become horny in old age, that’s for sure.” Here, in removing part of its outer layer, he would seem to be eroticising the building itself. One can map a certain subversive logic onto this. Ask Wyn Evans if he considers the replaced wall – “which is going to cost the ICA a lot of money” – to be his work as well, and he readily agrees.

On the one hand, it surely tickles him that the Mall, that corridor of royal power, is going to be partly stripped and exposed by a gay Welshman, and that something of that action will always be on show. (“It’ll change the way people appreciate the space at the ICA,” he says, “because they’ll know what it used to look like, and now it looks a little bit different.”) But on the other, that new brickwork will be a permanent monument to an impulse – a neutral impulse, one might call it – that can never quite be explained or contained; a permanent, prodding, glitch in the matrix. It is a cruel gesture; it is an utterly hopeful one. “I really, really believe in art. I really believe in its potential to change people’s lives,” says Cerith Wyn Evans. He is deadly serious, and the listener must pause and ask why, in 2006, those words sound so strange.

From the September 2006 issue of ArtReview – explore the archive.