The performance artist invites her audience to objectify her body in order to make a point about the objectification of women

In her performance and video works, Thai artist Kawita Vatanajyankur has been a vacuum cleaner, a toilet brush, a flying shuttle in a weaving loom, a crop sickle and a spade. Her latest projects see her exploring the role of humans and their labour in a world that will be (if it isn’t already) dominated by AI. The Machine Ghost in the Human Shell (2024) sees the artist hooked up to electronic muscle stimulators controlled by OpenAI’s GPT-4 large language model (she’s collaborating with Pat Pataranutaporn at MIT’s Media Lab on that bit). “I really wanted to have the AI fully puppet me,” she says, the work’s title inverting that of Masamune Shirow’s popular Manga series Ghost in the Shell (1989–97), which features a robot controlled by a human intelligence. Although she qualifies that desire by adding that she “could not be electrified all the time, otherwise I would die”.

Vatanajyankur was born in Thailand but moved to Australia at the beginning of her teenage years, staying on through university. She struggled to adjust to the move at first. She couldn’t speak the language and, she says, found it difficult to shake the Thai ideal of a silent, quiet woman being a perfect woman. By the time she returned home to Thailand in 2011, after graduating from Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, she was no longer quiet and no longer performed to the same social ideals. In a sense she had gone from being an outsider abroad to being an outsider at home. “I feel like an alien in both worlds,” she confirms. And that sense of the alien, alongside the expectations of what it is to be a Thai woman, has driven much of her art, which spans performance, video and installation.

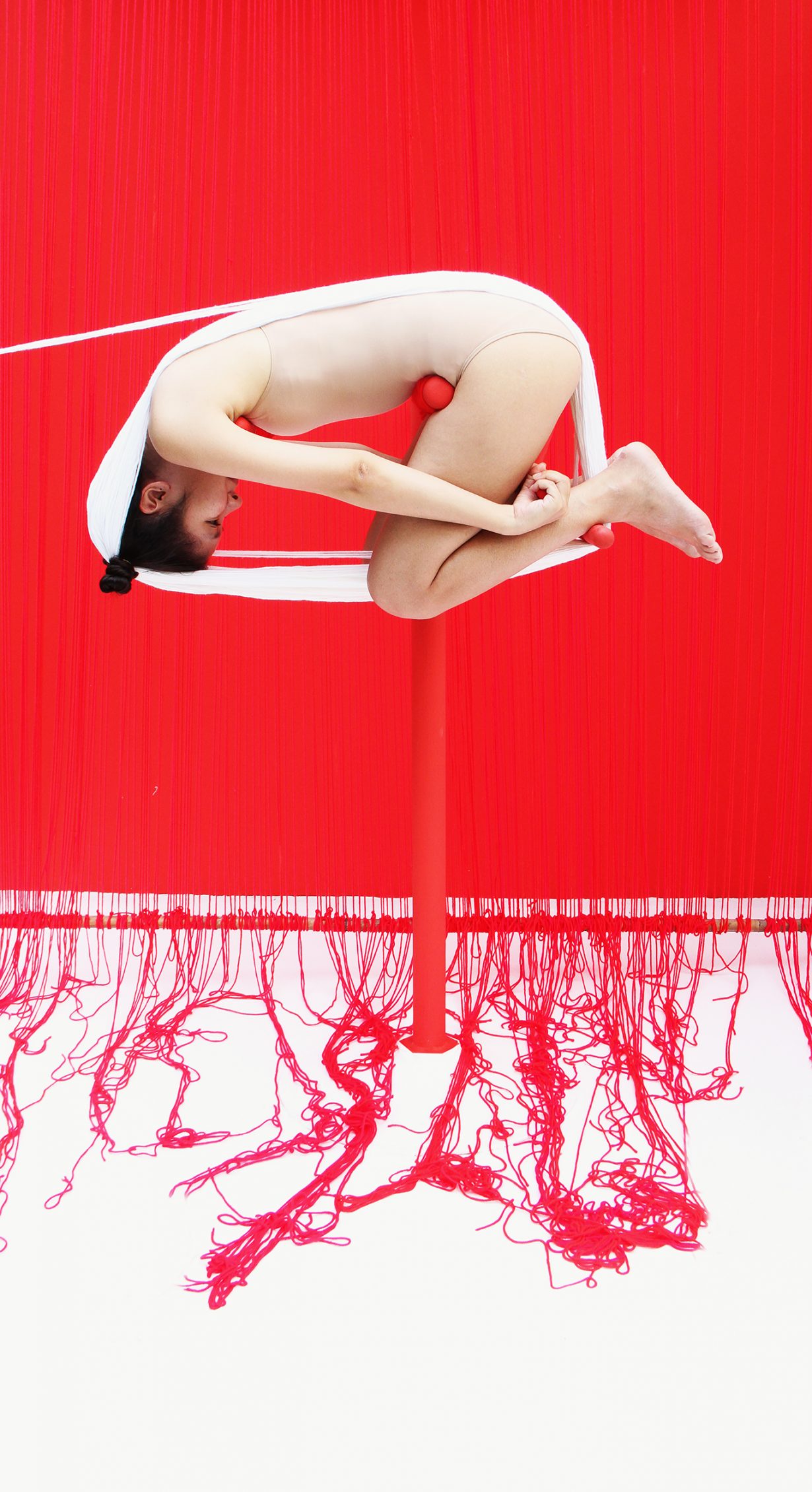

In Shuttle (2018, part of a series called Performing Textiles, 2018–19), both a performance and a videowork, the artist takes the role of a shuttle in a loom, passing through looped yarn on a loom. (In Spinning Wheel, 2018, she features as the mechanism of the title, her body curled up around and melding with the wheel’s large needles, spinning round and round to create the yarn.) In Shuttle, the yarn and its manipulation become her purpose or function, and a bondagelike entrapment, as she fights her way through, turning her own body into a cog in a machine. As in many of her works, she’s performing precisely that which she critiques, just as she invites her audience to objectify her body in order to make a point about the objectification of women. Women make up nearly 60 percent of workers in the garment industry globally and up to 85 percent of the labour force in Southeast Asia and India. In Shuttle the background is bright yellow, the loom itself is painted baby blue, the yarn looped onto it is bright purple and that which the artist is weaving through it (wrapped around her body) is bright red: bright Day-Glo colours that represent a cliché of Barbieland doll’s house femininity and projected happiness, and are typical of the artificial colour palette that is a feature of the artist’s work. Researching the series, Vatanajyankur visited factories in both territories, interviewing both owners and labourers, and witnessing a protest against labour conditions in Bangalore – conditions that have worsened with the advent of fast fashion, and which we, the consumers of it all, are confronted with as we consume her art. As much as it’s about ideals of colourful beauty on the surface, it’s about danger too: the risk of getting trapped in Shuttle, the risk of slippage and the needles in Spinning Wheel, and the total physical exhaustion too. “Embracing horror is part of life,” the artist says, before adding, “it’s the art of life. It’s something that if we grow through it, grow from it, grow out of it, we look back and we think that was beautiful.” Her point perhaps is that we, the audience for her work, as well as the ostensible performer and the actual workers her performance is based on, need to grow beyond our culture of exploitation. Although in her verbal articulation of the beauty of that pain it’s as if, again, she’s performing what she critiques.

In a way, it’s the artist’s deployment of idealised colours of beauty that magnifies the horror in her work. At first glance you would think it couldn’t possibly be about anything dark or unpleasant. But just as the garment labourers are conditioned to accept the dark reality of their jobs, we’re conditioned by advertising and merchandising (and to some degree by the history of art) to accept the message that life is good when we see bright colours. “The funny thing about every time I think of developing the work or think about the visual language of the work, I would think of something that people would think is commercially pretty, actually,” she explains. “I would think of the colours, compositions, all those theories that would probably make some people mistake it for a commercial image, for example. A candy-coated trick for people to be attracted to the work, and then, after a minute of watching the film, see the horror or the message,” she says, chuckling.

Sometimes, however, and despite the cheery colours, the horror is more obvious. In the two-channel videowork Plough (Plaw) (2020) the artist is both a tool and its operator. In one channel she’s kneeling, bent over, head immersed in a trail of topsoil. In the other she’s facing the other way, appearing to stretch and strain as she pulls (by a pink rope) her crooked double through the earth. On the one hand it’s a picture of the exploiter and the exploited. On the other it’s difficult to work out who’s working harder. Which leaves you wondering who they are working for. And whether or not there’s a message here about a tendency towards self-harm. In My Mother and I (Vacuum III) (2021) the artist’s mother, reading a newspaper, distractedly pushes Vatanajyankur’s stretched and stiffened body, her feet acting like a grip, her head on the floor and her mouth attached to a tube immersed deep into what looks like a cloud of dust, disturbed as her head sweeps the floor, as if she were a human vacuum cleaner. Your initial reaction is to fear for the artist’s health and safety; then you might think that this image simply reflects the air that we generally breathe in a world that we’ve so successfully toxified; then that this is an image about what we define as women’s work: the perfect housewife. Or how toxic it can be to be conditioned to aspire to such ideals.

“I think there’s something magical about the visual language,” the artist explains. “It’s something that’s very universal. When you see it at first, you might not think about the message yet, but it sort of sticks in your mind. You keep analysing what you saw. I think that’s what’s powerful about art. It doesn’t have to have a direct message, but it does. It’s the conversation between that art and your experience and your memory. Then I think through that process, something is changing within you. You’re thinking, you’re like really deep-thinking about it. Then you realise, ‘Oh yes, actually, this could mean that’. I think this is a very slow process of the mind, but through individual change, even a little bit, I think it matters. I think that’s what art is to me.”

Though her relatively short career to date, Vatanajyankur’s work has tackled the agricultural, fishing, textile and domestic-labour industries, all with a focused critique of their mechanisation and industrialisation, and how that has obscured the bodies of the (mostly) women who perform the work within them. Now it has turned towards AI and the ways in which its advent, and related technologies, might complete the job of corporeal obliteration: bodies ground down and disappeared by corporate, industrial or social machines. Currently she’s working on the development of a voice for the AI controlling her body, so that might go further to erase her personhood, replacing memory as well as intention, for a performance of The Machine Ghost in the Human Shell set to premiere at the upcoming Asia Pacific Triennial in Queensland. The AI will control movement in both her arms via electrodes, which sneak peeks on Instagram suggest is currently a little jerky. Nevertheless, the finished work will be a step into the future and a return to one of the countries she might call home – however disturbing she may have made the idea of homes appear.

Vatanajyankur’s work is included in The Spirits of Maritime Crossing at Palazzo Smith Mangilli Valmarana, a collateral event of the 60th Venice Biennale, through 24 November. The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial, organised by the Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, opens on 30 November