Wordplay, tradition and politics swirl around a collective of performers attempting to define ‘contemporary art’ in Kyrgyzstan

Chingiz Aidarov lives at 19 Zapadnaya Street in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan. To get to the multidisciplinary artist’s home, one must pass through two gates and follow a wall that Bishkek Feminist Initiatives (its previous occupant) stencilled with antipatriarchal graphics and slogans. In a large garden to the left, pear and apricot trees grow among metal sculptures he has made that blend Western and Kyrgyz references, like the one of Futurama’s Zoidberg wearing a kalpak. The mudroom of the house doubles as a shop selling artwork by Aidarov and friends. Beyond it is a room with his paintings of quotidian and pop-cultural figures, another where he sleeps and a kitchen decorated with a single wallpaper strip of pink orchids.

Aidarov’s friends found this home for him in autumn 2022 after a stroke paralysed the right half of his body and impeded his ability to speak. Though Bishkek rents were rising sharply due to the influx of Russians skirting the war – a trend common across much of the former Soviet world – the landlady gave them a deal which ensured that, with sufficient crowdfunding, he could live there for the foreseeable future.

It was in this house that the collective Zamanbap art came into being. Owing to Aidarov’s limited mobility, some of his collaborators from Art Group 705, a ‘nomadic theatre’ founded in Bishkek in 2005, traded their modes of performing in public space for those scaled to the intimacy of the home. Zamanbap art takes cues from Jerzy Grotowski’s poor theatre and Ramis Ryskulov’s tricksterish approach to poetry and art, creating gamelike scenarios, member Marat Raiymkulov told me in January, where “you can’t draw a line between sitting, being together and making a performance”. Since its inception, Zamanbap art has grown to include Salkyn Adysheva, Aizuura Bakalova, Azat Idrisov, Emirlan Jakshybaev, Mirbek Kadraliev, Aibek Mailybashov and Malika Umarova, among others.

Zamanbap is Kyrgyz for ‘contemporary’, and the word carries multiple meanings for the collective. Given the traditional conceptions of art practice that still predominate in the country, calling itself ‘contemporary art’ is a humorous yet sobering attempt to expand the field. The choice of language also has significance in that many members are fluent in Russian and speak broken Kyrgyz. They share a desire, Umarova reflects, to “build Kyrgyz anew”. As Aidarov began speech therapy, it felt timely to speak both languages in their work, embracing the mistakes and possibilities of a hybrid tongue.

Winter Theatre (2024), so named for the season when it was shot, exemplifies the collective’s domestic antics. The video unfolds as a nine-episode comedy partly inspired by CACA (2023), a ‘social science-fiction novel’ written pseudonymously by Bishkek curator and editor Gamal Bokonbayev. CACA (an acronym for Central Asian Contemporary Art) is at once a zip through planetary systems and a dissection of trends in the regional culture, ever subject to the influence of Western art markets, foundations and other institutions. In the episode ‘Maestro’, the charismatic Raiymkulov plays a reporter covering a ‘kitchen exhibition’ where Bakalova, banana-cum-microphone in hand, is singing operatic runs. “Everything here is art,” the reporter exclaims, “and we will even witness how I become an artist.” Taking the banana from Bakalova, he remakes Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (2019) and arguably improves upon it, adding a jammy fingerprint to the tape lest his authorship be in doubt. The episode ‘Where is the Fee?’ shows a “capitalist” haranguing two drunk beggars (played by Raiymkulov, Aidarov and a mask on a broomstick, respectively) about the “need to work!” Moments later, he crouches next to them, desperate to sell his goods. “Life is like this,” he moans – or at least, life under the prevailing economic order. Anyone can be cut down to size.

Differentiating all of these characters are cardboard and paper masks drawn in Raiymkulov’s irreverent style and informed by Aidarov’s past ‘invasions’. (Aidarov enacted Akayev apologises to the people in 2016 at Osh Bazaar, one of the busiest markets in the country. Wearing a mask of Kyrgyzstan’s disgraced first president’s face, he begged for forgiveness from anyone who would listen.) The ease with which a mask can be raised and lowered, Raiymkulov observes, lends to “the immediacy and improvisation” of Zamanbap art’s approach. It also has a social dimension. When I visited 19 Zapadnaya Street with Raiymkulov and Umarova last May, we turned leaves into masks and posed for one of Aidarov’s many Instagram stories. Wearing masks with others can foster a sense of camaraderie and collective possibility. In fashioning a mask, one must cut (even modestly) into the fabric of reality.

Throughout Zamanbap art’s relatively short existence, Aidarov’s home has been both the site for performance and a performer unto itself, shifting between genres as readily as members of the collective. The video Albarsty Classic (2024) turns the space into a haunted house, as seen through the eyes of a nurse who lived there during Aidarov’s first months of rehabilitation. Providing the voiceover for the work, she describes how an albarsty (a mythological figure said to paralyse and even choke a sleeper) would visit the house regularly and sometimes bring its entire family along. In the collective’s dramatisation, which diverges from her account, a woman arrives at dusk to the seemingly empty house only to learn of its numerous otherworldly occupants. Some receive conventional horror-movie treatment, as when a cardboard fly attacks the woman to the sound of shrill synths, and the albarsty studies her in a POV shot. But when the family gathers to watch television, the vibe is positively banal. Even the woman looks on with a neutral expression! In our conversation, Raiymkulov suggested that the “albarsty is also a mask: we don’t know what’s behind the mask, but what’s interesting is how we interpret the mask”. A threatening force, seen through another interpretive lens, may be something we can or must learn to live with.

Uncle Fantomas (2024) marked the latest transformation of 19 Zapadnaya Street. For this live event, a collaboration with Grace Rogerson and Jasmin Schädler for theatre-club MESTO D’s site-specific festival Place–Action, Raiymkulov guided audience members through the two gates, along the wall, into the garden and finally the house – often stopping to perform chapters of Aidarov’s biography. The cutout heads propped above the second gate, for example, voiced racist statements made by Aidarov’s landlords when he lived in Moscow from 2016 to 2021 as a migrant worker. In the period between his return to Bishkek and his stroke the following year, he created paintings and drawings that satirised a certain type of hypermasculine Kyrgyz man. By way of demonstration, Jakshybaev swaggered around the garden and ‘cut’ the necks of two metal sculptures of Ridley Scott’s aliens as if they were livestock.

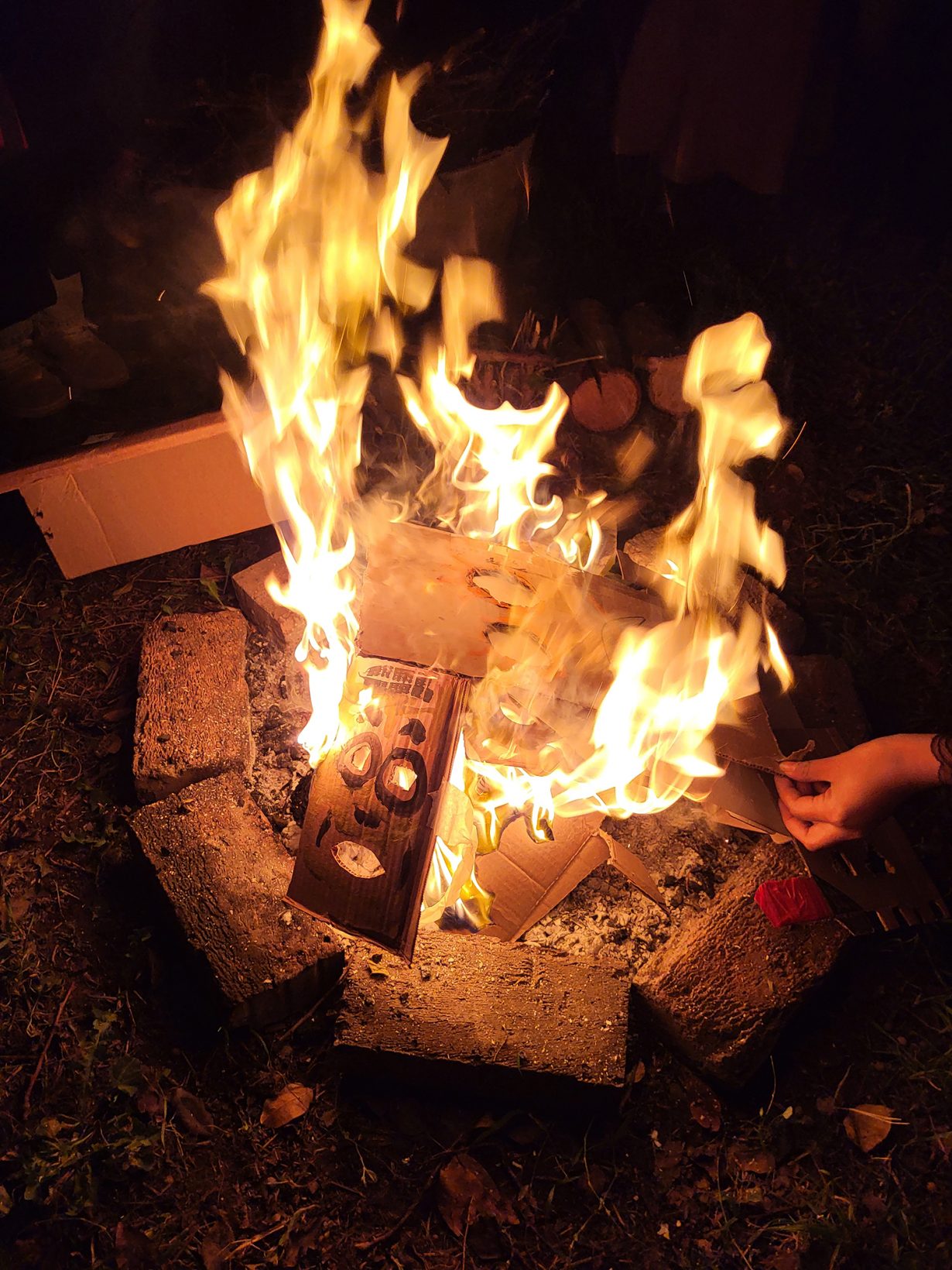

Upon entering the house, Raiymkulov displayed a number of Aidarov’s paintings and shared excerpts from his diaries, which were dramatised outside the windows by masked figures and cardboard speech bubbles. One scene made reference to a period in 2011 when Aidarov awaited deportation from Moscow. (En route to Marina Abramović’s The Artist is Present at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, he was arrested by police, as his documents had expired.) Instead of Abramović, Aidarov met several fellow deportees, including one who was given vague assurances by jail administration that working as a food server would allow him to remain in Russia. A later scene, based on Aidarov’s storyboard for an unrealised animated film, showed his exchange with a man in Bishkek (both played by cardboard kalpak-wearing Zoidbergs). The man asked for money, but Aidarov had none to give, so he imagined setting fire to the Bishkek White House – just as people did in the 2010 revolution to force the resignation of corrupt president Kurmanbek Bakiyev. Extending the ‘kitchen exhibition’ of Winter Theatre, Uncle Fantomas made the entirety of 19 Zapadnaya Street a living archive and museum, where Aidarov’s finished and unmade works, as well as his written anecdotes and ruminations, could take a turn on Zamanbap art’s capacious stage. His life and practice were the atmosphere of the event, and the artist himself – still in the midst of rehabilitation – was also very much present. Aidarov, pumping a fist to Raiymkulov’s rap. Aidarov, sharing knowing looks with his old friend. Aidarov, opening the second gate to confront the spectres of landlords past and welcome us into his home.

Tyler Coburn is an artist, writer and teacher based in New York.

Interpretation from Kyrgyz and Russian was provided by Malika Umarova.

From the March 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.