What’s next for the contemporary art biennial, now that the era of neoliberal globalisation that shaped it starts to unravel?

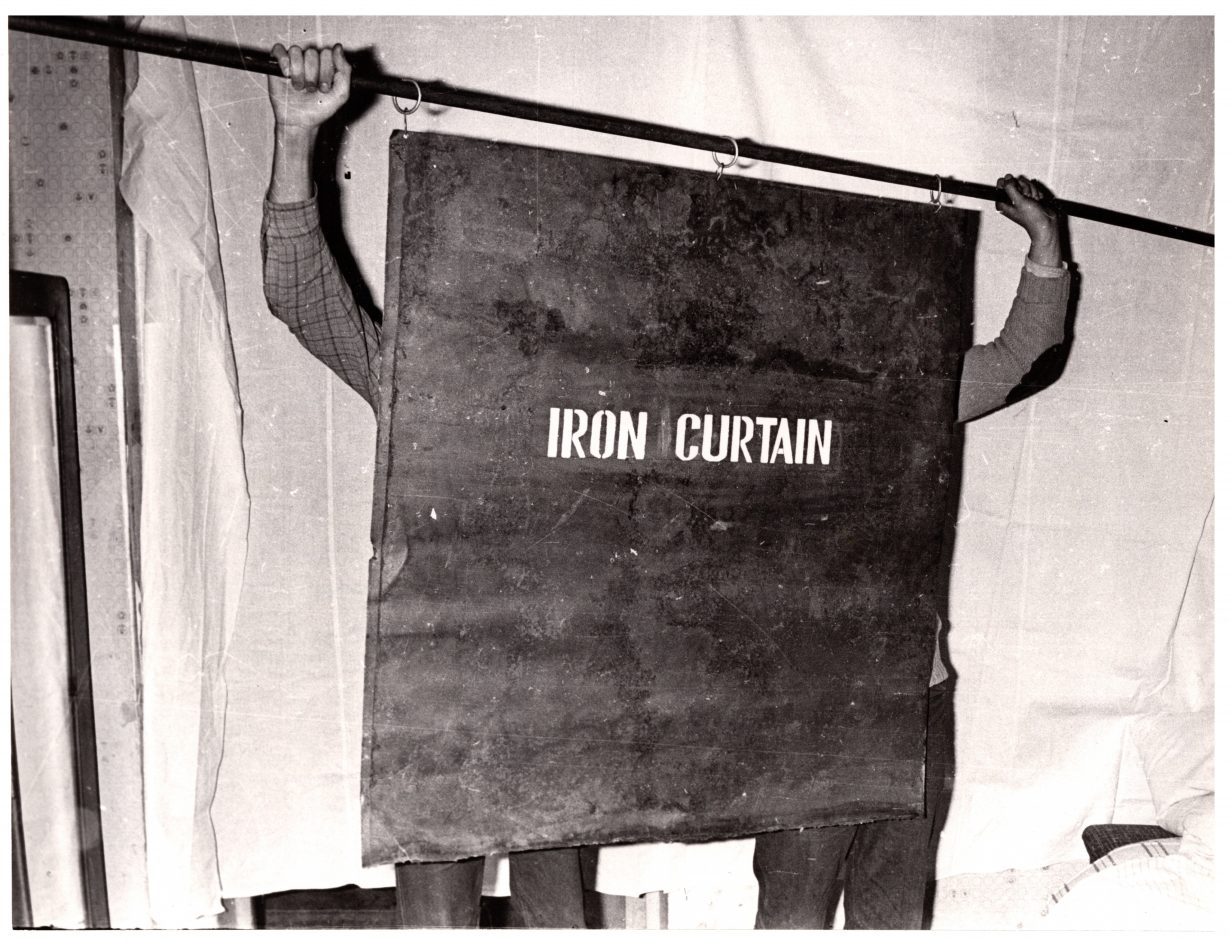

This year marks the 60th edition of the Venice Biennale. Less noticed is the fact that it’s also the 50th anniversary of the edition that, in one sense, didn’t happen. After the edition of 1968, which featured art-student protests and riot police, and following several years of controversy over how the Biennale should be run, the new president, the socialist Carlo Ripa di Meana, recast the mission of the organisation, taking it, for the next three years, in an explicitly political direction. This was not business as usual: the national pavilions were shuttered, the previous model of historical surveys was abandoned and the summer schedule shifted to October. The 1974 edition became ‘The Biennale for a democratic and anti-fascist culture’, committed to staging art, theatre and cinema that protested against the Chilean dictatorship that had overthrown the leftwing government of Salvador Allende the year before. Then, in 1976, though the exhibitions of the national pavilions returned, Ripa di Meana framed the main exhibition and the edition’s theme as a ‘Homage to Democratic Spain’, at a moment when Spain had endured four decades of the right-wing regime of General Franco. And by 1977 the maverick president was planning the ‘Biennale of Dissent’, a showcase of unofficial Soviet art, theatre and film by artists either still in the USSR, or Russian dissidents living abroad. The edition, which finally opened on 15 November 1977, was loudly decried by the Russian government, and put into question the loyalties of the Italian Communist Party, while bringing Ripa di Meana’s new approach under intense domestic political scrutiny. By 1978, Ripa di Meana had resigned, and the Biennale was reestablished in the form that has endured since – independent presentations in the national pavilions and a common largescale exhibition, put together by the Biennale itself.

Nevertheless, the events of that decade are a reminder that while the Venice Biennale – oldest of all the biennials – tends to appear to be a permanent and immovable presence in the global art system, it has never been immune to pressures for change or contemporary politics, or, at its most radical, to the possibility of disappearing altogether. And yet the history of the politically engaged Biennales that Ripa di Meana instigated, for a brief moment, was quickly forgotten.

During the four decades that followed, the Biennale morphed progressively into an event that both reflected and drove the artworld into the age of globalisation, which accelerated, following the end of the Cold War, from the 1990s onwards. As Carlos Basualdo noted in his 2006 essay ‘The Unstable Institution’, after the Biennale’s founding in 1895 it would take ‘five more decades and two world wars to found the São Paulo Bienal (1951)’. Yet ‘in the brief interlude of fifteen years, from 1984 (the year of the first Havana Bienal), to the [end of the twentieth century], more than fifteen international biennials have been established’. Basualdo argues that the biennial form is the cultural expression of globalisation, a phenomenon ‘reflected precisely in the growing proliferation of this unstable institution of the largescale international exhibition’.

But if the ‘largescale international exhibition’ of contemporary art is a relatively recent phenomenon, closely tied to the realities of globalisation, it might be that the period that drove its expansion is coming, if not to an end, then to some kind of juncture. The politics in which largescale exhibitions of the Western artworld operate is changing fast. As the Biennale’s 2024 edition gets ready to open, it already finds itself faced with the conflicting aspects of the shifting culture of globalisation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, that conflict lies in the reemerging tensions between nationalist and internationalist agendas. In this, the Venice Biennale’s peculiar hybrid identity, as at once a showcase for the reality and the idea of the nation-state, and also a platform for a different supranationalism, has come to the fore. That hybrid identity, meanwhile, pulls into focus the particular character of largescale exhibitions: that of the global curator.

Foreigners Everywhere is the title of the international art exhibition element of the Biennale, curated by Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa. It’s the slogan for a critique of the politics of national identity, of borders, of state-hood and statelessness, that, according to Pedrosa’s curatorial statement, will privilege those seen historically as political, social and cultural ‘strangers’; ‘the queer artist, who has moved within different sexualities and genders, often being persecuted or outlawed; the outsider artist, who is located at the margins of the art world, much like the self-taught artist, the folk artist and the artista popular; the indigenous artist, frequently treated as a foreigner in his or her own land.’

It can, of course, also be read as a rebuke to the political context of contemporary Italy, and contemporary Europe more broadly. This edition of the Biennale is the first to open under the populist right-wing government of Giorgia Meloni, which came to power in October 2022, on a ticket of cultural traditionalism and curbing immigration, this last also a reflection of the fact that immigration and the control of borders is becoming a major electoral issue across Europe. With the Meloni government’s appointment of rightwing journalist and commentator Pietrangelo Buttafuoco as the Biennale’s new president, some observers worry what this might mean for the Biennale’s artistic independence and culture of internationalism. Tensions over the politics of internationalism, the nation-state and the Biennale’s independence have also surfaced in controversy over Israel’s participation, in the wake of the latest developments in the Israel–Gaza conflict. An open letter signed by over 22,000 calling for the Biennale to exclude Israel prompted Italy’s minister of culture to intervene directly, with a statement excoriating those who ‘think they can threaten the freedom of thought and of creative expression in a democratic, free nation like Italy’. Meanwhile, the campaign group Art Not Genocide Alliance (ANGA) denounces what it sees as the double standards of a biennial that supported Ukraine following Russia’s invasion in 2022. Now ANGA is demanding the ostracisation of Israel’s representation by participants, press and visitors. And yet autocratic countries like Saudi Arabia and China are present at the Biennale to little criticism, suggesting that both the needs of European diplomacy and the priorities of protesters continuously shift and change.

Whichever side one takes, or whether one takes sides at all, it’s evident that the tensions emerging in world politics are starting to fracture the benign, if vacuous, internationalism that has underwritten not only the Venice Biennale but the wider model of the biennial during the era of globalisation. Arguably, that model was always only really credible when ‘globalisation’ meant the kind of world order governed by an unchallenged West, dominated by a hegemonic US. But that unipolar world order is now a more fractious and unstable multipolar world. And one of the cultural aspects of that unravelling is the growing challenge of the Global South to Western-centric perspectives in the biennials organised outside the West, but also the arrival of those perspectives within the global biennials of the West.

The incorporation of overlooked and ignored voices of the Global South was the rationale for the engagement of Indonesian collective ruangrupa as artistic director of Documenta 15. It also frames the appointment of Pedrosa, the first South American curator of the Biennale. Both of these appointments allow these very Western, very European institutions to signal their commitment to current postcolonial curatorial agendas. As Basualdo perceptively noted in ‘The Unstable Institution’, while museums ‘are, first and foremost, Western institutions… the global expansion of large-scale exhibitions performs an insistent de-centering of both the canon and artistic modernity’. What he saw as a novel development during the 2000s (particularly with Okwui Enwezor’s groundbreaking Documenta 11 in 2002) has now become a frequent rationale in largescale exhibitions: from Documenta to Venice; from the Bienal de São Paulo to the Biennale Jogja. Common to many of these curatorial projects is the emphasis on international and transnational solidarities over national ones.

This points to a development that is too little examined in the evolution of the biennial or largescale exhibition, perhaps because its development is assumed as a given; the role and status of the curator. There were not always curators of contemporary art at the Biennale; until the 1970s, the large group exhibitions staged alongside the national pavilions tended to be art-historical surveys, intended to reconnect an international public with the art of the earlier twentieth-century, a history that had been obscured and suppressed by the rise of fascism in Europe and the disruptions of war.

But by the late 1960s, critics agreed that this art-historical function had largely been achieved. So in 1968, the British critic Lawrence Alloway could observe the shortcomings of the Venice Biennale, concluding that, ‘at present, the Biennale is formed as always, by the participating countries’ send-ins, over which Venice has no say, and by random conglomerations on the labyrinthine walls of the Central Pavilion.’ ‘What is necessary now’, Alloway wrote, ‘is to discover a means to confer order on the thick samples of present activity.’

What Alloway was looking for – though the figure had not been named yet – was the curator of contemporary art; the individual who, even in 2006, Basualdo could call ‘a relatively unfamiliar figure’, now needed to ‘negotiate the distance between the value system [of] the critic and art historian, and… the ideological pressures and practices corresponding to the institutional setting in which such events emerge’. Six years after Alloway’s comments, the Venice Biennale was rebooted by a radical director who turned the antique institution into a platform for political art, engaging with geopolitical issues well beyond the bounds of Venice or Europe. Ripa di Meana’s experiment eventually hit the hard limits of national politics and Cold War diplomacy. What emerged out of it was a Biennale that retained the old form of the national presentations, but which would host increasingly influential curated exhibitions of contemporary, rather than historical art; exhibitions whose curators, in the decades that followed, became more representative of the global artworld, and whose exhibitions, like the many other largescale exhibitions that would soon appear, became the ‘means to confer order on the thick samples of present activity’.

In a letter to the New York Review in September 1977, ahead of the ‘Biennale of Dissent’, Ripa di Meana argued that ‘Art inevitably creates a tension between itself and society, its conventions, accepted ideas, established ideologies, prejudices, and conventional morality. How a society absorbs these tensions, how it deals with the defiance posed both by art and ideas – these are questions that have been of concern to the Venice Biennale.’ That concern, however, was that of a curator siding with a more activist agenda for art, and willing to mobilise an entire organisation to political intervention, destablising, in the process, the unspoken compromise between politics and art on which the biennial model is founded. Today, largescale exhibitions are again becoming sites of political contestation and conflict, shaped by the ending of the era of neoliberal globalisation once led by the West. But as the controversies over Documenta highlighted, these conflicts are arising because while curatorial agendas have globalised and internationalised, at the level of national politics electorates are turning away from the globalist perspective, as evidenced by the rise of populist political movements and governments in Europe and the US. As contemporary curators advocate, through biennials, for a postnational view of the future, they are starting to encounter the turn away from the globalist view taking place across the West. The biennial of contemporary art, born of neoliberal globalisation, may not survive that contradiction. The only question is – what comes next?