THE 1970s: _____ at Argos Centre for Audiovisual Arts, Brussels captures a world both embracing and resisting technological advancement

Featuring 30-plus artists and artist groups, THE 1970s:_____ aims to chronologise and draw attention to the scope of film and video art that emerged in several Belgian cities (including Aalst, Antwerp, Brussels, Liège, Namur and Knokke) during a particularly frenetic decade, setting down an as-yet-unwritten history in consultation with the artists and filmmakers involved. A recurring leitmotif in the show is how cultural production in the early part of the decade was dramatically transformed by the arrival of new recording devices, particularly video cameras. There is, accordingly, an archaeological quality distinguishing the exhibition: moving-image material originally produced on formats that were at serious risk of deterioration and decay has been tracked down, digitised and resuscitated.

Two widely available video-recording devices developed by Sony, the reel-to-reel Portapak (1967) and the cassette-based U-matic (1971), proved particularly important in this era and were used in many of the works included here. But this decade also saw more traditional film technologies (such as the Super-8 camera) being used in experimental ways. Bernard Queeckers’s Hexagon 2 (1976) consists of a Super-8 camera suspended on cables inside a geometric structure made from mirrors partially visible to the viewer; the camera spins at speed, filming its own blurred reflection. Rudimentary in concept and realisation, this work typifies the type of ‘structural’ work that emerged in Belgium during this ‘laboratory phase’, when it was sufficient merely to explore the technical capabilities of these machines, and, by extension, the impact of this technology on human perception.

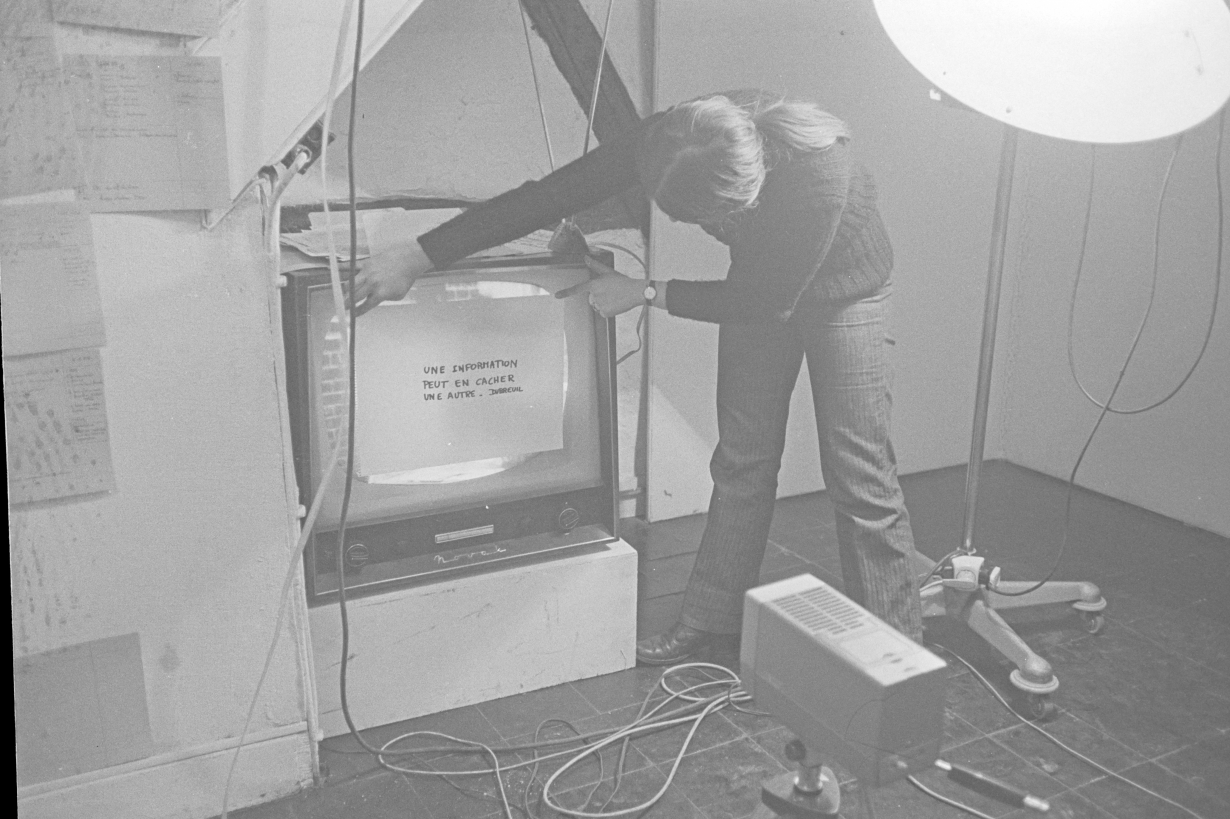

Elsewhere, in the upstairs gallery, a reconstruction of Jacques Lizène’s 1971 installation Sculpture Interne sprawls across the floor. A camcorder and spotlight point to the rear of a vintage cube-shaped monitor, the back casing removed to reveal its innards, which are then shown in real time on the monitor’s screen via a live closed-circuit feedback loop. Sculpture Interne naturally evokes Nam June Paik’s mid-1960s work, and the influence of the Korean artist – who was exhibiting widely in Europe in these years – is tangible throughout this show, both literally and more generally in terms of a subversive approach to hijacking technology. While recording devices were still novel at this time, TV was firmly established, and artists such as Lizène sought to liberate it from its use as an apparatus of ideological control and cultural hegemony.

That TV could be a two-way mode of communication was central, too, to a four-day-long 1971 project initiated by Guy Jungblut and others at the Yellow Now gallery in Liège. Artists’ Proposals for a Closed-Circuit Television invited a constellation of artists to suggest ways of activating such a setup in the gallery. The contributions from European and American artists – Dan Graham, Christian Boltanski and Gina Pane among them – underscore the international reach of this project; that this venture took place in a regional, postindustrial city in Wallonia is notable, too, given the region’s less prominent cultural and economic position compared to its wealthier Flemish counterpart, in what is a linguistically and (more recently) politically bifurcated nation.

The revolutionary implications of audiovisual technology interested many artists at this time, particularly those of a Marxist or Situationist bent. Such ideological aspirations unified a swathe of artists working with audiovisual media and independent filmmakers opposed to mainstream culture. Entities such as the Montfaucon Research Center, a collective active in Brussels from the late 1960s to the early 70s, used film with the aim of fomenting change and altering sociopolitical mores. The centre was cofounded by Michel Bonnemaison and Joëlle de la Casinière, the latter notably prolific after the centre disbanded. De la Casinière is represented here by Telecolor Inflammable (1977), a mantric, psychedelic, loosely narrated film that harnesses the trance-inducing powers of the flickering screen.

There is a tension within much of the work here between a desire to embrace technology while also resisting its perniciously homogenising and standardising influences. If this decade-specific compendium shows us anything, it is how, in a relatively short period, technology once viewed as imbued with utopian potential can be assimilated and institutionalised, its insurgent and disruptive capacities entirely neutered. Inevitably, then, THE 1970s:_____ feels elegiac and nostalgic, casting electronic light on one of the last gasps of a culture shaped by the social and ideological shifts of the previous decade: a scene built on self-organisation, informal underground networks and a shared belief in the potential of collaboration.

THE 1970s:_____ at Argos Centre for Audiovisual Arts, Brussels, through 18 December