Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from Sharjah Biennial 16 to Pap Souleye Fall in New York

Sharjah Biennial 16: to carry

Various venues, 6 February–15 June

Sharjah Biennial 16, titled to carry, presents an exploration of the things that we hold – physically, emotionally and culturally – across time and space. Addressing themes of precarity, migration, inheritance and survival via the work of more that 190 artists, to carry is curated by Alia Swastika, Amal Khalaf, Megan Tamati-Quennell, Natasha Ginwala and Zeynep Öz, whose projects, at various points, converge in a single venue. Some projects will form cross-cultural connections between different voices and perspectives, while others stand alone as distinct narratives. It appears that this edition of Sharjah Biennial is as ambitious in concept as it is in physical scope: to engage in a shared journey, where multiple perspectives, histories and artistic expressions intertwine and reflect on change, resistance and the possibilities of transformation is no mean feat. One work to look out for: Luke Willis Thompson will be presenting a new film, set in 2040 and featuring Māori newscaster Oriini Kaipara, who delivers an impassioned monologue advocating for plurinationalism (a political and legal system of governance that allows for multiple nations to coexist in a single state) and the ethics of restoration. Fi Churchman

Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 8 February–1 June

How many ways can you primp, shape and restrict the normative ideal of the female body? The faceless feminine figures in the paintings of Christina Ramberg (1946–1995) pull and push against their sartorial constraints, from black-banded stockings to pointed bustiers, painted red nails and shiny corsets that suck them in at the waist. ‘Shiny, shiny, shiny boots of leather’, sang Lou Reed in ‘Venus in Furs’ in 1967. The tension between domination and submission is well-documented, amped up to absurdity in Ramberg’s playful focus on the fetishistic rituals of so-called femininity. Active as an artist throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Ramberg is often associated with the Chicago Imagists, known for their often surreal, acerbic take on pop and consumer culture. Ramberg brings an eye for precision and detail to her works, which span not just paintings but quilts, installation, sketchbooks and other ephemera (including an adapted dressing table mirror), many of which will go on show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in her largest retrospective to date. Her skill lies in her ability to pick away at the edges of female self-presentation, from bouffant hairstyles to sexualised underwear, by framing these cosmetic trappings in cropped and dismembered fragments that only serve to highlight their highly selective nature. In cutting these sartorial gestures up, she draws attention to what is hidden as much as what is revealed, and plays a game of show-and-tell that ultimately reveals the bizarre fantasy of it all. Louise Benson

Hawai‘i Triennial 2025: ALOHA NŌ

Various venues, 15 February–4 May

ALOHA NŌ, the fourth iteration of the Hawai‘i Triennial, explores the notion of ‘aloha’ – both a greeting and a philosophy of mutual regard, sovereignty and ‘truth-telling’, as theorised by the scholar-practitioner Manulani Aluli Meyer. Featuring contributions by artists and collectives exhibited across over a dozen venues on O‘ahu, Hawai‘i Island and Maui, three of Hawai‘i’s some hundred islands, the triennial considers ‘aloha’ as an ethos that could inform efforts to remediate ecological damage and inspire healing and solidarity among people. The 49 exhibitors from Hawai‘i, the Pacific and elsewhere include Honolulu-based interdisciplinary artist Nanci Amaka, whose performances often employ visual idioms of domestic labour to reflect on rituals of stewardship and care; visual artist and filmmaker Jane Jin Kaisen, whose recent work focuses on the women divers of Jeju Island, South Korea, who make their livings harvesting abalone, octopus and other delicacies from the sea; photographer Lieko Shiga, perhaps best known for her chromatically intense Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Coast) series (2008–12), which she made while working as the official photographer of the town of Kitakama, Japan; and lens-based artist Edith Amituanai, whose portraiture highlights the everyday lives of Pasifika and other diasporic subjects in New Zealand. Jenny Wu

Shilpa Gupta

Bikaner House, Centre for Contemporary Arts, New Delhi, through 14 February

The works of Mumbai-based artist Shilpa Gupta centre around speech, as well as its limitations – be it habitual or enforced. In her For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit, first installed at the Venice Biennale in 2019, she suspended 100 microphones in the gallery room, each reverse wired to work as a speaker playing words by poets who have faced political persecution. On the floor below, sheets of paper containing the same lines have been pierced by metal spikes, reminding us that voices can permeate imposed boundaries, that the act of speaking itself can be monumental. Similarly in the series Listening Air (2019–22), on view at Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi, protest songs from different moments in history emanate from similar microphones-turned-speakers. While Untitled (Spoken Poem In A Bottle) (2021–23) displays a series of glass bottles, into which she had spoken lines of poems then sealed them in with lids, questioning whether voices can be contained or preserved – or whether they can resonate without a sound. Coinciding with India Art Fair this February, as well as another solo exhibition at Ishara Foundation in Dubai, the show will explore the limits of borders that are simultaneously rigid and porous. Yuwen Jiang

American Photography

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 7 February–9 June

In an unauthored daguerreotype, dated to between 1870–75, a man – wellingtons, weathered workjacket, a beanie darker than shadows – and a woman – eyes averted, her pinafore scraping the dry grass – stand before a small factory (Grant Wood’s American Gothic would not appear for another fifty years). Who has decided to photograph these two strangers? This is photography’s ability to be at once specific and yet remain enigmatic. Next, a 1915 candystore catalogue, for which the Schadde Brothers carefully painted delectable colour onto Gelatin silver prints; our contemporary eyes can barely discern the trick, its verisimilitude so ingrained in the visual style of modern advertising, but their deception was radical. These early works capture the existential conflict at the heart of American photography: works that speak to, about and for human life; and that can also shift bills. The Rijksmuseum will surely hope to achieve both, with this gathering of over 200 works presenting ‘the country as seen through the eyes of American photographers’, and that ‘shows how the medium has permeated every aspect of our lives: in art, news, advertising and everyday life’. You can expect to see works by the likes of Ming Smith, whose genius captured something monumental in the everyday humanism of her street and social portraiture; the experimental filmmaker Hy Hirsch’s abstract, swirling, jagged 1950s C-prints (screensavers were never the same again); Irene Poon’s dedication to capturing the Asian American community, using light and exposure as a kind of visual metaphor for emotional sensitivity; and Bryan Schutmaat’s grand 2012 portrait of Nevada’s declining industrial landscape. Alexander Leissle

Paulo Nazareth: Patuá/Patois

WIELS, Brussels, through 27 April

Back in 2011, Paulo Nazareth produced a work that established him as one of Brazil’s most important artists in a generation: for ten months, he walked from his home state of Minas Gerais through South America, Central America, Cuba and into the United States. The trip was subsequently documented by objects he picked up along the way (packaging and the like) and numerous photographic self-portraits, either with people he met or mostly in which he holds signs offering his labour for survival, or more pointed messaging (‘I am American too’, reads one scrawled on cardboard). In the intervening decades his work, veering more towards sculpture and painting, continues to dissect how innocuous objects or actions can be embedded with stories that refuse to go away: the series Egg of Columbus, 2020, for example, features dubiously branded produce from Brazilian supermarket shelves – the package illustrations racialised, the company names harking to colonial times – sealed in resin; Várzea, 2020, a series on concrete-cast footballs, each with a knife embedded point-end; the 2018 graphite and watercolour series Blacks in the Pool, showing lush but charged scenes of swimming. Each are vessels of history on their own journey through time. Oliver Basciano

Pap Souleye Fall: HIDDENINPLAINSIGHT

Stellarhighway, New York, through 15 March

Mixed-media and manga artist Pap Souleye Fall populates his assemblages and installations with an eclectic constellation of cultural signifiers including legumes, costume pearls, cowrie shells, West African amulets and references to video games and Marvel movies. In January, Fall filled a downtown Manhattan gallery with a large cardboard peanut – an agricultural export of Senegal, where he was raised – which visitors could enter like children crawling into a DIY fortress. His latest exhibition, HIDDENINPLAINSIGHT at the Brooklyn apartment gallery Stellarhighway, most prominently features a fabric installation resembling a patchwork greenscreen that covers one of the gallery’s walls. Besides being adorned with small objects and embedded with images, the screen, titled KEYEDUPKEYEDOUT (2024/25), also seems to be camouflaging a deconstructed corporeal form (perhaps a motion capture performer who’s been sucked into its surface?). On the opposite wall, a mixed-media work, similarly verdant, titled GRIGRIGREENSCREEN (2025), possesses two dewy, cartoonish ‘Kirby eyes’ and is embroidered with a trapunto-style whirlpool at its centre. In Fall’s amalgamations, which voraciously imbibe cultural symbols the way the video game character inhales other creatures (and a greenscreen devours a person dressed to match it), consumption is figured as a means of relating to – and even salvaging – the increasingly abundant artefacts of our physical and digital worlds. Jenny Wu

Cemile Sahin: ROAD RUNNER

Esther Schipper, Berlin, 1 February–5 March

A few words: surveillance capitalism, the military industrial complex, postcolonialism. These, avid brain-people will know, are some of the defining forces of twenty-first century society – all insidious and invisible to the naked (read: ordinary) eye. Intentionally so. What if we could see it all at once, or as close to that as possible? The work of the Kurdish artist and novelist Cemile Sahin is concerned with the myriad ways in which power, technology and media interact, and the lives they (are often designed to) impact. Paired with a taste for pop colour across gallery-filling installations, panelworks and film, Sahin’s works feel for the friction everpresent in contemporary life: between violence and innocence. Sahin’s new exhibition at Esther Schipper Berlin, Road Runner, has at its centre a new film of the same title. Flanked by 16 new panelworks – each a variety of lurid inkjet print onto aluminium – and block-text running continuously around the room (a la Liam Gillick), the film combines traditional cinematic storytelling with drone footage, pastiche commercials, animation and videogame-play to tell the story of Bêrîtan, a girl struggling to free her sister from ‘digital captivity’ in an imagined future run by killer drones. It’s all dialed up, but never truly alien. Alexander Leissle

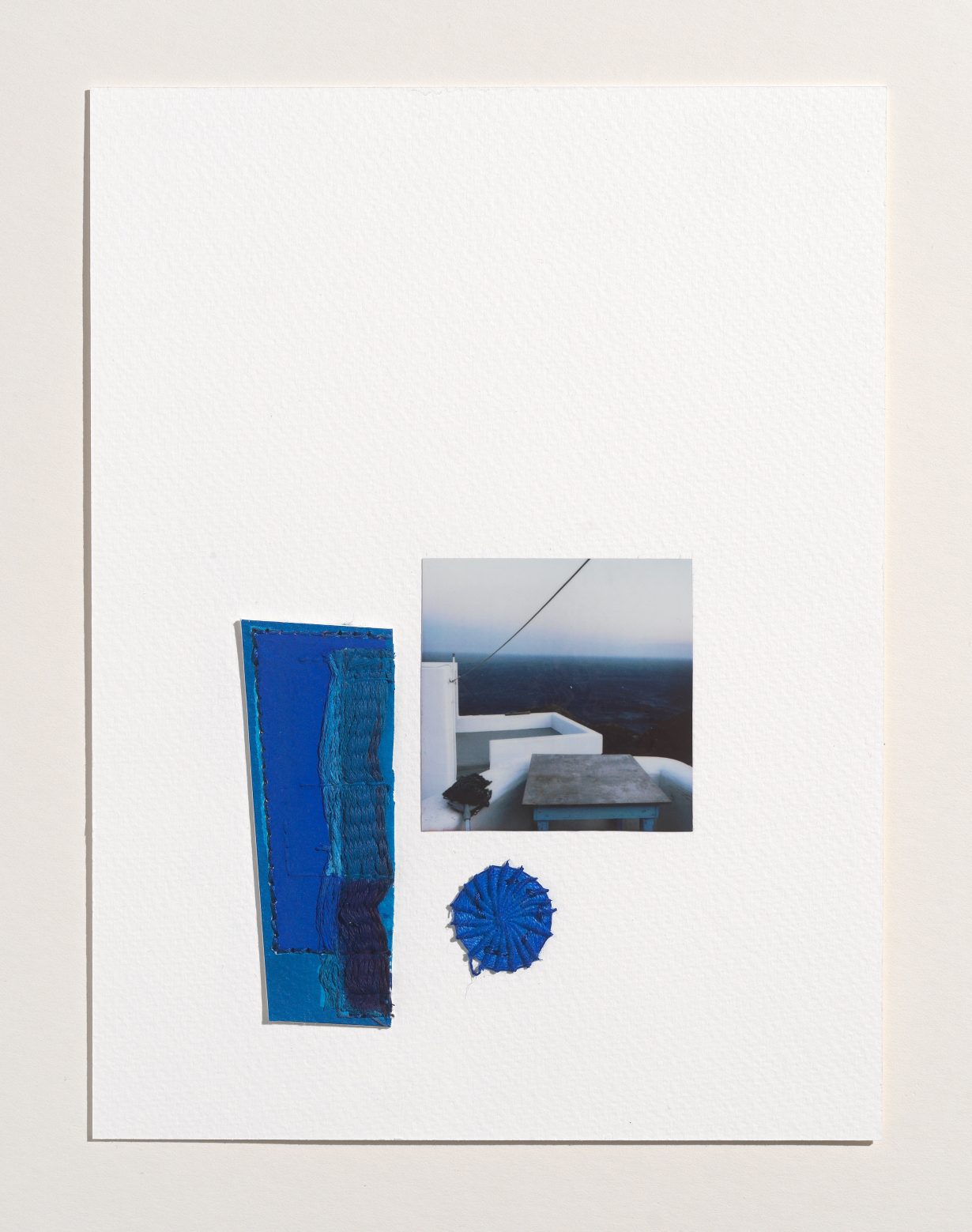

Majd Abdel Hamid: Ode to the Sea

Marfa’ Projects, Beirut, through April 2025

There is a pebble that has accompanied me through multiple homes, rooms, and what feels like multiple lives. I weighed the tiny stone in my hands after finding it in the cold depths of a rock pool on the edge of the Atlantic, saving it from the wave that would otherwise pull it right back out into the ocean. Now it travels with me. I thought of my pebble when I saw the crocheted cotton fabric, spools of string, soap and other found trinkets brought together in Ode to the Sea, Majd Abdel Hamid’s wistful, evocative show of fragments taken from the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. The artist has described the evolving body of work as a travel journal of sorts, a growing collection of otherwise fleeting objects that crossed his path and caught his eye in the Tunisian islands of Kekennah, Beirut, and Anafi Island in Greece. Coils of thread are pressed into bars of soap or displayed alongside photographs of the water as seen from the coast. In one photo, two chairs are left empty in the foreground against the blue of the horizon behind, as if recently vacated, while others are framed through open windows and against tiled walls. Hamid is less interested in escapist fantasies of untouched nature than he is the human relationship with the water. It still feels difficult to consider an exhibition staged in Beirut (which was so recently under siege from Israeli airstrikes) by a Palestinian artist whose homeland has been decimated by 15 months of war, without that political context shaping its interpretation. The sea is a site of migration, of hope and as well as danger, and of freedom. Yet there is something radical and liberating in the immediacy of Hamid’s visual compositions of personal memory, not seen as a metaphor for something else but simply existing as they are. Louise Benson

Machine Love: Video Game, AI and Contemporary Art

Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 13 February–8 June

As Freddie Mercury once asked, ‘Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?’ Given the steady creep of artificial intelligence into our lives, where we are now is a bit of both. Or at least that’s what is proposed by the works in Mori Art Museum’s international group exhibition Machine Love: Video Game, AI and Contemporary Art. The show brings together 13 artists who make use of machine learning and generative gaming systems to create new, hybrid landscapes and identities. The videos and live-simulation installations here are part-human, part-machine collaborations, as with Anicka Yi’s algorithmic, biomorphic ‘paintings’, or Lu Yang’s videogame avatar journeying through its Buddhist afterlife. Look out for an astronaut in silver spandex stalking a barren terrain, in Beeple’s video installation Human 1 (2021) and the corporate office space in Sato Ryotaro’s video Inorganic Friends (2023), crowded with a menagerie of werewolves, wrestlers, ninjas and aliens – a kind of meeting place for all the videogame characters we sometimes inhabit. These entities are who we share this new landscape with, so here’s a chance to spend some quality time getting cozy with them. Chris Fite-Wassilak