The artist’s portraits of figures both real and imagined refuse easy assumptions around their social context

Sylvia Snowden once described the first painting she made as a ‘social statement’. She was referring to a work from 1962 that depicted washing lines hung across the porch of a dilapidated house. In 1978 the artist turned to destitution once more, with a series that was initially titled Displacement and later renamed M Street. But here she took a different approach. In that year, Snowden moved to Shaw, a historically Black neighbourhood in Washington, DC, then seriously deprived, and found herself with a new subject matter: the people who lived on her street. Prior to this relocation, figures had already become the centrepiece of her paintings, and the thick, concentrated brushmarks seen in M Street were in place. But these earlier figures were mostly fictionalised creations – not necessarily responses to specific people the artist had come across in real life. Of her neighbours in Shaw, Snowden stated in an interview last year: ‘We did not socialise. I watched them from afar. I would name [figurative paintings] after a particular person as a means of identification for a work – not as a portrait.’ The ten M Street works displayed here, which date from 1978 to 1997, might be titled after ‘Sandra’ or ‘Patricia Ann’, but such choices, then, feel arbitrary rather than essential.

Critics writing about these paintings, as well as the artist herself, have highlighted the social and economic circumstances of these men and women, who, in effect, were not much more than reference points for Snowden, so one question that prevails in this exhibition is what role, if any, this context plays when considering M Street. Two of the earliest works in the exhibition immediately reveal the artist’s expressionist tendencies – evidence of the priority given to paint itself, rather than subject (Snowden calls her style ‘structural abstract expressionism’). Paula Black (1978) and Clarene Martin (1978–82) are hung side by side, an imposing pair, each canvas spanning almost 2.5m in height. The brushstrokes are dense but still animated enough to create a circular sense of movement around the canvas. At this stage in the series, Snowden appears to be a colourist: her palette is a harmonious warm mix of pink, peach and indigo that reinforce what look like long, dark brown legs – bodies can be made out here, and they are on the move.

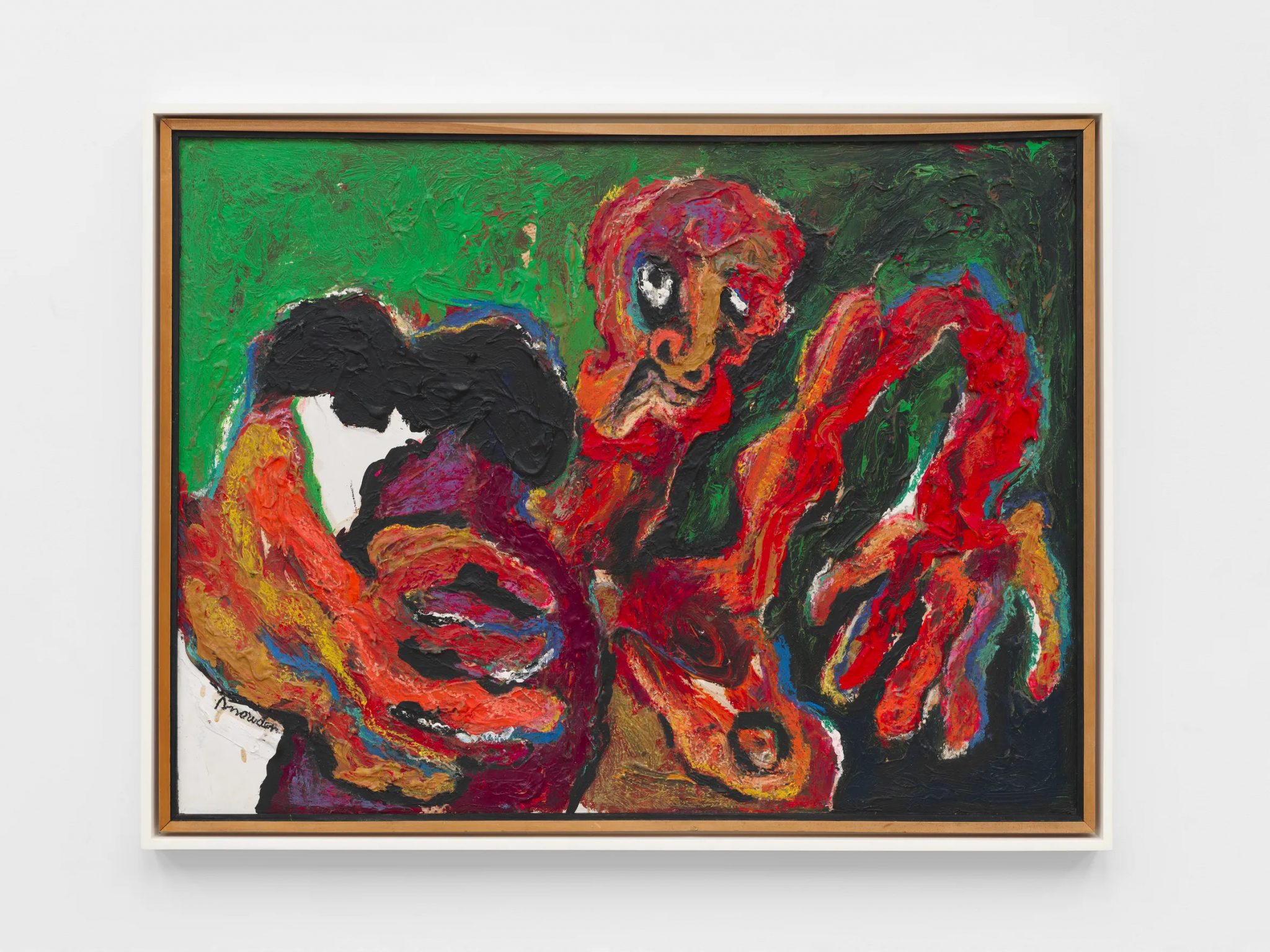

Later in the M Street works the artist becomes fixated with a lurid palette dominated by red, black, green and mustard, and the abstract forms have been replaced by a recurring figure with long, splayed-out fingers and warped limbs. In developing this fanciful archetype, Snowden establishes what feels like a single character whose arms and legs she simply rearranges. Eyes appear rudimentary (Ethel Moyd, 1984) and bodies take on static postures (Miss Leslie Mae, 1982, looks like a seahorse, with her protruding chest and curled torso). The most recent work depicts a jarringly toned giant figure placed on top of a plain white background: a faceless form with rigid oversize arms (Theresa Black, 1997). The formal components of the painting might be the focal point here, but they don’t lead to something else.

Commentary on M Street has often focused on its commemorative function: as a tribute to hardship. Given the distance established between the artist and her subjects, that seems implausible. But even if knowledge of that context is absent, Snowden’s impressions of people still fail to materialise as just that: bodies are put forward, but the feeling of a person is largely absent. The artist made a point of not showing the paintings she made to the people who informed them but recalls their jubilance when the paintings were collected from Snowden’s house, on their way to a gallery: that’s because they could see their name written on the back of the canvas. The visibility that they might have been anticipating in the painting was only really captured by its title.

Sylvia Snowden at White Cube Paris, 15 October – 16 November