As I write this, British voters are getting ready to elect a new government (election day is 8 June). The election was called in April, on short notice, after incumbent prime minister Theresa May claimed she needed a new mandate in order to govern with strength and authority. And with the snap election, another, slightly less important appointment also had to be made in a bit of hurry. Starting with the 2001 election, the UK parliament has commissioned an ‘official election artist’ to cover each general election campaign and make a work in response to it. On 1 May, sculptor Cornelia Parker was appointed to this unusual position; Parker, if you’ve been following her on Instagram lately, has been travelling the country, attending various election events (the leaders’ TV debates, manifesto launches and suchlike) and snapping bits of newsprint and online media, alongside moments of everyday life, in order, presumably, to tap into the mood of the country.

artists in the UK seem too often to opt for the political platitudes of a particular cultural and social outlook

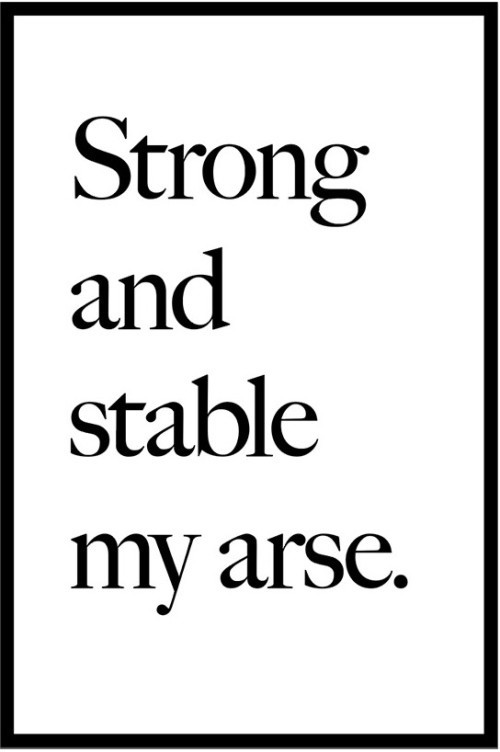

Contemporary artists in Britain like to get involved in domestic elections. During the 2015 election, artist Bob and Roberta Smith ran against Michael Gove, the Conservative education minister at that time, to protest the Tory-Liberal coalition’s sidelining of the arts in education; last year, in the EU referendum campaign, Wolfgang Tillmans led the most visible artworld opposition to Brexit, issuing pro-Europe posters that gained widespread media attention while spawning a whole culture of anti-Brexit poster memes. And in the current election campaign, Jeremy Deller has confirmed that he’s the author of a campaign of street posters with the snappy slogan ‘Strong and stable my arse’ – satirising May’s questionable ‘strong and stable’ campaign theme. By contrast Grayson Perry, an artist never shy of the public eye, has more recently taken to mocking an artworld synonymous with the much-maligned ‘metropolitan elite’. Discussing Brexit in a Guardian interview, Perry declared, ‘As an artist I find it exciting. No doubt it will be a disaster, but also any chance to stick it to my fellow Islington liberals is great.’

Perry’s mockery of the liberal elite is ironic, since he himself has become part of the ‘official’ scenery of contemporary art in the UK – from giving the BBC’s prestigious Reith Lectures to presenting a string of TV programmes. Perry’s comments, of course, go ahead of his solo show at London’s Serpentine Gallery, titled knowingly (at a moment when the shadow of ‘populism’ hangs over the confused state of democratic politics) The Most Popular Art Exhibition Ever!, and set to open on election day.

But both Perry’s cheerful anti-elitist posing and Parker’s more stuffy and solemn engagement as the ‘official’ artist of the election beg a more basic question: why should we be looking to artists to offer a ‘special’ take on a country’s political life at all?

Grayson Perry, ‘Red Carpet’, tapestry, 2017. Image: courtesy the artist, Paragon | Contemporary Editions Ltd and Victoria Miro, London (photograph Stephen White)

Grayson Perry, ‘Red Carpet’, tapestry, 2017. Image: courtesy the artist, Paragon | Contemporary Editions Ltd and Victoria Miro, London (photograph Stephen White)

Maybe it’s a measure of how much contemporary art has come to be seen as part of ‘official’ culture in Britain that one artist who cross-dresses and another known for blowing up sheds should find themselves in such demand. But Britain’s political establishment has a long history of absorbing artists into its discreet system of patronage, from handing out ‘honours’ for services rendered to appointing ‘official artists’. And this cosiness is often cultivated by artists who desire public recognition and are keen to enter the intricate but opaque influence networks of government, funding bodies and the media.

Perry’s mockery of the liberal elite is ironic, since he himself has become part of the ‘official’ scenery of contemporary art in the UK

While artists relish the attention, it’s the political establishment’s love affair with contemporary art that produces such odd gigs as the ‘official election artist’: it’s no surprise that the commission was dreamed up in 2001, the first election after the rise to power of Tony Blair’s New Labour, with its neophile obsession with contemporary culture and the creative industries. The 2001 election artist was the society portrait painter Jonathan Yeo (son of former Conservative cabinet minister Tim Yeo). Yeo produced three terrible portraits of the main political leaders, with an equally dreadful conceptual twist: the three canvases were sized according to the three main parties’ share of the vote. The were titled, in an act of entirely toothless criticism, Proportional Representation – echoing the recurring gripe of British electoral politics that the composition of parliament doesn’t reflect the proportion of votes cast for smaller parties.

Yeo’s idea now has a sort of crazy prophetic irony – after decades of squabbling over proportional representation, the British political class is reeling from the shock of a straightforward, majoritarian democratic decision, with huge political consequences. Contemporary artists in the UK have, by and large, tended towards the pro-Remain position of the political establishment; those few like Perry, who like to bait their ‘fellow Islington liberals’ in favour of Brexit, do so because they sense that there’s a problem with being too close to the ‘official’ position, too remote from public opinion.

It’s hard to see how appointing an artist to ‘represent’ an election can produce anything but nonpartisan platitudes. At the same time, artists in the UK seem too often to opt for the political platitudes of a particular cultural and social outlook – the ‘metropolitan liberal elite’. So while it would be regressive to argue that art and artists shouldn’t comment on what’s going on in society, it would be good to argue for more discord, more contradiction and division of opinion – more creativity. Perhaps the ‘official election artist’ will surprise everyone, and truly ‘represent’ the diversity of the will of the people, not just the partial opinions of artists…

From the Summer 2017 issue of ArtReview