Charles Ray, Art Institute of Chicago, through 4 October

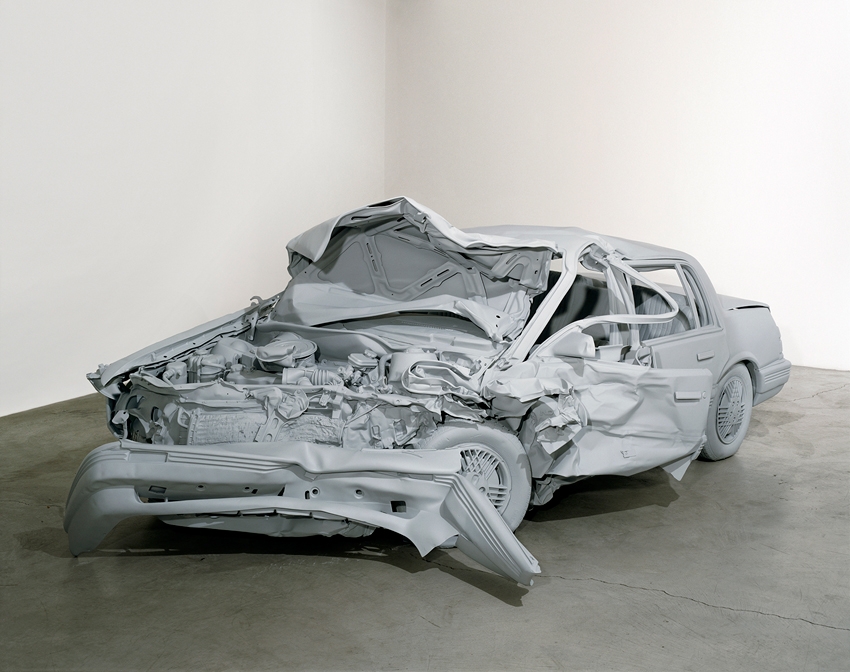

Charles Ray’s career is spangled with outré anecdotes. There’s the time the la-based Chicagoan – famed for exacting sculptural paeans to, inter alia, bodies, trees, fire engines and crashed cars – dismantled a defective tractor, had its thousands of internal and external parts hand-sculpted and cast in aluminium, fitted them together and then sealed the structure, making much of the painstaking work inaccessible (Untitled (Tractor), 2003–5). Or the time he spent a year looking for the ideal fallen tree, not knowing what he’d do with it, and made Hinoki (2007), which entailed moulds of the rotted and insect-chewed trunk, a fibreglass reconstruction and master wood carvers in Osaka. (The work, whose own future decay is a conceptual factor, has a lifetime pegged at 400 years.) Or the time he reacted with surprise to an interviewer’s noting that the eight sexually interlinked figures in Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley… (1992) all bore the artist’s own features, as if that were irrelevant. Or the fact that his artworks can frequently take a decade to produce. The results, combining strict mimesis and attentive poetics, the technically boggling and the psychologically ardent, constitute a small but near-faultless and ultrageeky corpus. Its most recent portion, 19 works dating from 1997 to 2014, graces the leading art institution of Ray’s birthplace from mid-May onwards.

Momentum 8, various venues, Moss, 13 June – 27 September

From Ray it’s a quick skip to tunnel vision, the phrase subtitling the eighth Momentum, the Nordic Biennial. Moss, the Norwegian coastal town to which, between 1913 and 1916, Edvard Munch withdrew, is, as curators Jonatan Habib Engqvist, Birta Gudjonsdottir, ArtReview contributor Stefanie Hessler and Toke Lykkeberg point out, a locale appropriate to their theme of narrowed attention in a networked world, either through disconnection from the external world via immersion in digital life, ‘a renewed interest in psychotropic substances in society at large’ or the ways in which collated user data covertly pilots our online experience. Aficionados may not be amazed to see the brightly addled visuals of Ryan Trecartin, Daniel Steegmann Mangrané and Agnieszka Kurant on display, along with works by 21 others; that shouldn’t, though, blind viewers to the savvy syncretism of the curatorial conceit.

Olaf Breuning, Metro Pictures, New York, through 1 August

If he weren’t a little outside the apparent age demographic, Olaf Breuning could conceivably fit among those numbers, given that his works have frequently dealt with characters who can’t see past their own noses. The Swiss-born New Yorker’s series of videos Home (2005–12) in some ways anticipates Trecartin’s work while being a withering critique of American mores: specifically, living life as if starring in one’s own personal movie, the world merely your changing backdrop. The simpleton main character, a gap-year global-traveller type, babbles stories about his adventures abroad and in America, or, in the second and third films, welcomes us into them. What carries over from the Home series to the new, nonfilmic works at Metro Pictures, we might expect, is the idea of a figure riding an excess of stimulus, with varying degrees of grace. Expect circular collages where ‘anonymous characters’ sit amid chocolate coins, brain models, rubber breasts and more, and mirrored sculptures onto which these frenetic images are reflected.

Paul Chan, Deste Project Space Slaughterhouse, Hydra, 15 June – 30 September

For the past six years, Dakis Joannou’s Deste Foundation has mounted an annual show by marquee names in a converted slaughterhouse on the Greek island of Hydra. This time, following turns from Matthew Barney and Elizabeth Peyton, Doug Aitken and Urs Fischer, among others, it’s Paul Chan’s opportunity to do with it as he likes. Fond of historical parallelism (and, of course, silhouetted animations), he’s a logical choice, here engaging with Plato’s provocative early dialogue Hippias Minor (or On Lying), in which Socrates argues for parity between truth-tellers and liars and says it is better to do wrong voluntarily than otherwise. Chan addresses this with three outdoor sculptures and a new translation of the text, introduced by the artist and copublished by his Badlands Unlimited imprint, in which, apparently, the emphasis will be on the issue of whether Plato wasn’t trolling so much as arguing for the act of voluntary lying that constitutes the creative act.

Terrapolis, Neon, Athens (at the French School), through 26 July

A short distance away in Athens, the nonprofit Neon Foundation of another big Greek businessman collector, Dimitri Daskalopoulos, is holding its second collaboration with London’s Whitechapel Gallery, Terrapolis. More outdoor sculptures are on view (as if Athens didn’t already have plenty of those); here, under the curatorial auspices of Iwona Blazwick, artists including Allora & Calzadilla, Huma Bhabha, Enrico David, Sarah Lucas, Richard Long and Yayoi Kusama, and five Greek artists making new commissions, are apparently looking at ways to reconnect the human to the animal under the sign of ‘bioethics’. The image we’ve seen is of one of Kusama’s giant pumpkins (or bobbed Kusama hairstyles), which, in this context, tilt genetically modified as well as psychedelic.

Max Mara Art Prize for Women: Corin Sworn, Whitechapel Gallery, London, through 19 July

Meanwhile the Whitechapel itself, seemingly unable to resist collaborating with institutions in sunny Southern Europe, is, as is its two-yearly wont, hosting a show by the winner of the latest Max Mara Art Prize for Women, Corin Sworn. The prize is based on proposals for work that the artist would make on residency in Italy. In the London-born, Glasgow-based artist’s case, the props, lighting and costumes in her installation hew to her longstanding interest in the construction of narrative out of fragments but are also apparently inspired by the sixteenth-century theatre troupes of the commedia dell’arte: expect thematics of deception and mistaken identity – reflecting the style’s influence on Shakespeare, a tidy English link – and, of course, masks.

Alex Israel, Almine Rech, Paris, 13 June – 25 July

Alex Israel is a thoroughly modern cultural producer. His work, often revolving around artworks – particularly pastel panel paintings – that suggest props and backdrops, is closely tied to his experience of Los Angeles and the star-making machinery of Hollywood in particular. Seductively glossy and easy on the eye, it might seem analytical, acquiescent, or to situate acquiescence as a conscious position. Israel has referenced the doyenne of Angeleno disaffection, Joan Didion (As It Lays, 2012, a collection of deadpan, borderline-banal interviews with SoCal glitterati, echoes her novel Play It as It Lays, 1970); he also has an eyewear line. At Almine Rech, amid conscious trackbacks to his last show at the gallery, one of Israel’s Backdrop Paintings, effectively 2D props made by Hollywood artisans, meets another prop of sorts: a sculpture of a Chevy Corvette by a cactus tree. ‘Alex Israel would probably not be displeased to be considered as a sort of cool Michael Asher, totally adjusted to the reality of an artistic field violently reconfigured by the Internet and its acceptance of the rules of the Spectacular Society,’ curator Eric Troncy writes in the press release. Nicely phrased.

Will Benedict, Bortolami, New York, 12 June – 1 August

Israel’s fellow Angeleno Will Benedict takes a more explicitly aggressive, or even defeatist, attitude towards banality: his 2008 Post Card series of paintings, for instance, found him inserting small, semiabstract canvases into sheets of mottled foamcore, as if the painting were a stamp, enabling circulation; he’s since embedded other images in the same surface, and likes to photograph collectors and artists in front of these signature-style works, the ‘painting’ thereby receding into the realms of production and reproduction, and finally behind a pane of glass. Here, more foamcore panel paintings – featuring charcoal drawings of a gorilla and bedrooms – are accompanied by a music video Benedict made using Detroit band Stare Case’s queasy song Bed That Eats, based on the 1977 B-movie horror Death Bed: The Bed That Eats, which Benedict’s gallerist informs us is ‘a major cultural touchstone’ for him.

Carlos Bevilacqua, Galeria Fortes Vilaça, São Paulo, through 20 June

And that’s quite enough West Coast and visually appealing exposure of the structures that underpin cultural production. Let’s move on to, well, literally exposed structures, namely those of Carlos Bevilacqua’s sculptures, precise and delicate assemblies of lead weights, wood and strings predicated on showing their workings: how they’re held in tension and balance, how they might move. The Brazilian artist’s physics-laden, elegantly machined, lyrical work can resemble an orrery, a mobile, a children’s toy. Here, he presents three new sculptures that promise a philosophic aspect as well as, or instead of, a science demonstration: The Inexorable Path of Knowledge (all works 2015), a trio of vehicular designs appearing as if postcollision, a clocklike wall piece, Mute Geometry, and Isolation Bridge, a stile-like sculpture that connects, complexly, only to itself.

Mona Hatoum, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 24 June – 28 September

Maker of famously ferocious sculptures and installations reflective of instability and violence – whether in war zones or in domestic spaces – Mona Hatoum is also, when you dig into her oeuvre, adept at more delicate proposals that nevertheless reflect the exigencies of exile. These are related themes for the Lebanese-born Palestinian artist, who emerged from performative body art and from being stranded in London during the mid-1970s when the Lebanese war broke out, but whose works at once enfold and exceed such biographical specifics. The Pompidou’s lavish retrospective is set to do precisely such digging, revealing, via approximately 100 works from the 1970s to the present, that Hatoum’s 40-year career has accumulated any number of kinaesthetic highlights: the glowing heating elements, like lethal metal prison bars, of Light at the End (1989), the disorienting roomful of empty wire lockers creating seasick shadows thanks to a motional lightbulb in Light Sentence (1992), the giant kitchen graters resembling tortuous room dividers in Paravent (2008). The present writer may remember her as the testiest interviewee he’s ever encountered. Her best work, though, is for the ages.

This article was first published in the Summer 2015 issue.