A few pages into Lutz Bacher’s 2008 artist book, SMOKE (gets in your eyes), there’s a photocopy image of a square sheet, maybe a napkin, two columns of words handwritten on it. ‘Lute Bateau’, it reads, then ‘Klutz Backer’. The mutations continue, the artist’s unknown real name vanishing behind variations on her longstanding pseudonym. On the next page is a triplicate definition of ‘Lutz’: evidently this could mean a few things, including the pet form of Ludwig, and derive from German or French. Soon after, in a reproduced email, someone (name redacted) tries to define what is ‘Lutzian’: qualities ranging from ‘moments of particular social rupture or awkwardness’ to ‘bizarre behaviour in general, particularly around women’ to ‘moral horror’. Paging on, we find a curator writing to the artist after watching 12 hours of videotaped interviews in which Bacher asks artists, framers and gallerists to describe her: ‘…as if, after all those hours, I still believed there was such a thing as knowing you’. Many such conversations are transcribed in a 2012 book, titled (like the videowork) Do you love me?, replete with attention-derailing ums and typos: a generous self-exposure that isn’t an exposure at all, rather a cortege of chaos. Here and not here, c’est Lutz.

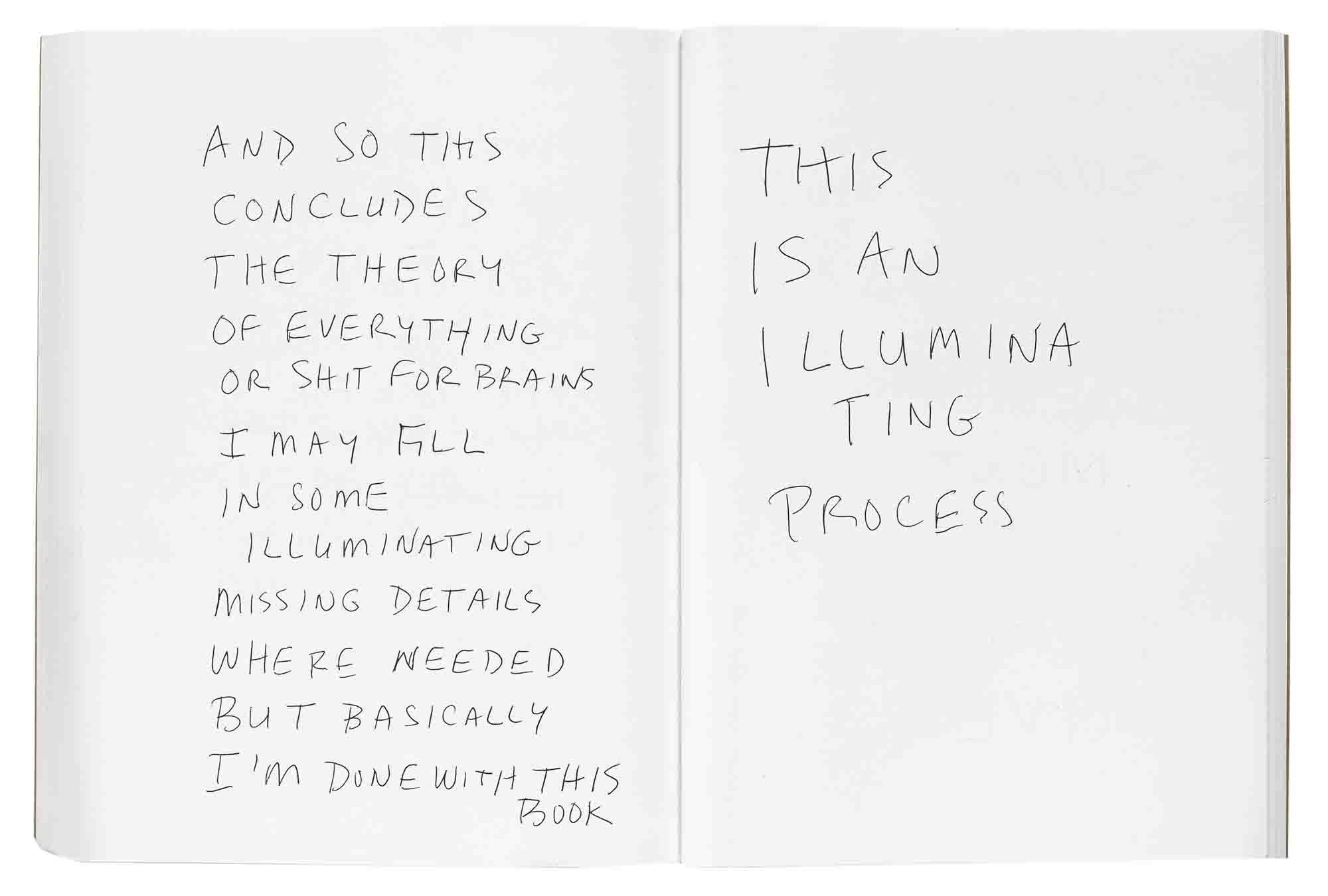

I’m looking at the handful of online photographs of her, taken at private views, where she’s always dressed in black. In some she’s covering her face, in others she doesn’t bother. I talk to one of her gallery directors about interviewing her. He says sometimes she will, sometimes she won’t. I don’t pursue it; he tells me some things – her age, a recent bereavement – that are enough, too much already. He hands me the galleys of Bacher’s next book, Shit for Brains (2015), a wayward, confessional, fearless little ‘novel’ she handwrote on A4 sheets in 2010, leaving in the crossings-out. It reads as puked up quick-from-the-heart and yet issued out of absence.

Here and not here has been Bacher’s modus operandi since the mid-1970s. Her approach has been constantly to shape-shift

Here and not here has been Bacher’s modus operandi since the mid-1970s. Her approach has been constantly to shape-shift, deny her authorial signature, disperse like smoke. Back in 1976–77 – years when her gender was unrevealed – she worked with photography both found and self-produced, artist’s books, interviews, video, performance. Her artworks already barely resembled each other. Men at War (1975) comprised cropped photographs of groups of men ‘whose central figure wears both a US Navy cap & a swastika painted on his chest’; in The Milk Video (1976), ‘a man had a dream where I was drinking a glass of milk’. Standard Stoppage (1976) offers blurry photographs of a tree; in Documents of Rape (1977), snapshots and diagrams anatomise a possible sexual assault. Several things are going on in this nexus of proposals. A pluralistic approach (au courant during the 1970s but peculiarly fitting and instrumentalised in Bacher’s case); a nod to Marcel Duchamp’s chance-driven work 3 Standard Stoppages (1913–14) that might also salute Duchamp’s own gender fluidity (as Rrose Selavy) and postmedium elusiveness; a complex of thoughts around masculinity and male power, from soldiers to dreamt-of ‘milk’-drinking to rape. In the midst of this, there’s an artist who, her wilful aesthetic already signals, will not be possessed or processed. After this sequence of works is reproduced in Bacher’s chronological 2013 catalogue, SNOW, she melts away for five years, appearing to produce nothing at all. Whatever the actual reason, such structural absences scan as congruent with her practice; the ‘work’ itself as composed partly of art objects, partly of an enigmatic performative aspect; and all of this, in turn, a meditation on the self. ‘A biography is considered complete if it merely accounts for six or seven selves, whereas a person may well have as many thousand,’ writes Virginia Woolf in Orlando (1928). Bacher’s biography, if she plays this game to the hilt, may never be considered complete. This, after all, is the artist who, in 2008, made Bingo (Or the Year I Was Born), a bingo sign with numbers programmed to light up in random sequences). Even if you didn’t care when Bacher was born, or what her real name is, she continues to point to the fact that she’s not telling.

If you want to be systemic about the artworks she has made, though, they’ll permit that to an extent. They often vouchsafe an aesthetics of betweenness, conscious undecidedness: consistencies arise only to implode later; where variation seems to rule, links will eventually appear. Consider James Dean (1986), two crossfading slide images of the fabled actor. In one he’s looking right; in the other, left. No one view is more definitive, plus the image itself is destabilised: it stands for more than a pair of publicity shots, opening onto some uncharted, ambiguously metaphoric realm. Preexisting images, Bacher has repeatedly averred, are not fixed. People aren’t either.

So the media image becomes the readymade, which comes to lose its initial semiotic sense; which blows it open; which makes it, in turn, analogical. Specifically, this process engages gender concerns, then capsules them within the problem of typologies and their relation to power. In the series Jokes (1985–8), unconnected obscene captions are applied to media images. (Jane Fonda is seen to say, at a press conference, ‘I’m really weird. I’m really all fucked up.’) In Sex with Strangers (1986), blown-up black-and-white porn images pair with captions from ‘a sexually explicit paperback written in the mode of a sociological study’. In a 1992 article for Artforum, Liz Kotz writes that the captions, ‘in their lurid accounts of female nymphomania and wayward hitchhikers, veer between voyeurism, parody, and the fauxscientific tone that lends vintage porn its campy tenor’; they fail to anchor the images, Kotz continues, sending them spinning out of control. Bacher’s occupation of images by men, for women, meanwhile, creates a space of productive ambivalence – it suggests that the fixity of gender roles is the problem, and the best thing to do, via a rewiring of the gaze, is to explode it.

She would continue, for a while, to regularly inhabit roles typically assigned to men, and to work with masculinity, domination, selfdefence. See Playboys (1991–3), paintings and drawings based on illustrations from the men’s magazines; numerous works around the same time connected to rape and child abuse, like male adult anatomical dolls; Shooter (1993), a video of Bacher firing handguns. In fuguelike fashion, though, maleness is deemphasised – it will flare up again, at later points – and replaced by other stresses. Child abuse segues into childhood (which had briefly reared its head in Mechanical Reproduction, 1983, a progressive enlargement of a photograph of a baby) and the psychology of the parent–child relationship, in disturbing ways. (Talk to Me, 1994, is a pink sack ‘that contains a foetus’.) Then this, in turn, recedes – for several years, Bacher appears focused on observational and documentary video that either makes her an invisible flaneur or deflects attention from her – but in 2005 she cycles back, making works featuring trolls and boys in pilot uniforms and incubators and pregnant mannequins. Even change, she suggests, can be reversed upon lest it be recognised as an aesthetic of change.

Yet for all the interpretative potential that might be suggested by the patterning above, one could track through Bacher’s oeuvre and find different, equally uneasy, indefinite, though insistently personal repeated foci. Her relationship to other artists, say. Beginning again with Standard Stoppages and Bacher’s gender-fucking, we can glimpse an ongoing conversation with other, mostly male artists, not dissimilar to (though less extreme and ventriloquised than) that performed by Sturtevant: Duchamp regularly, from the use of readymades to the broken mirror, The Big Glass (2008) to the giantchessboard- and-sculpture work Chess (2012), with its bicycle wheel, to the rubber Toilet (2013); Dan Flavin and Jasper Johns in the pink fluorescent light Pink Out of a Corner (To Jasper Johns) 1963 (1991); and Warhol repeatedly – from the a, A Novel-like recordings and transcripts of Do you love me?, to works relating to Jackie Kennedy, to Sleep (1996), a real-time performance and CCTV video of Bacher sleeping in the Gramercy Park Hotel, to her 2015 multichannel video of the Empire State Building, numerous others in between. There are references, in Bacher’s titles, to Jorge Luis Borges, David Foster Wallace, Blinky Palermo, Jackson Pollock, Spies Like Us, Van Gogh, The Beatles, Dr Seuss, Jimi Hendrix, The Way We Were, J.G. Ballard, Camper van Beethoven, George R.R. Martin…

One might read such work, coming after four decades of artworks that point, however obliquely, to the depredations of life on earth, as a dream of escape

‘Constellation’, though an increasingly overworked term in art discourse, might be a catchall to employ here, and Bacher, appropriately, has worked with constellations themselves. In 2011 she produced The Celestial Handbook, 85 framed pages of found imagery of the heavens – spiral galaxies, Alpha Centauri, nebulae, comets, star clusters – from amateur astronomer Robert Burnham, Jr’s 1966 book of the same title. One might read such work, coming after four decades of artworks that point, however obliquely, to the depredations of life on earth, as a dream of escape. But the heavenly photographs – imperfect transmissions, while fitting into Bacher’s tendency towards glitch-laden, raw photography and film and object-making – also convey themselves within another, open-ended, stream of her work that deals with the literally unearthly.

In 1996, Bacher filmed Blue Moon through the window of her house in Berkeley, California (she’s more recently moved to New York): a work that ‘ironically literalizes’, as Caomhín Mac Giolla Léith has written recently, ‘the precise meaning of a phrase most often deployed metaphorically – a second full moon appearing in the same calendar month – in that the refraction of the moon’s image through the window pane and/or camera lens produced a second moon, which was smaller but clearer, on account of the optics involved’. In her 2013 exhibition at Portikus, Frankfurt, Bacher embedded video monitors showing this work in a lunar desert of black coal slag. By the time it travelled to the ICA in London, the black desert, Black Beauty (2012), supported Ash Tray (2013), a plangent and vaguely humanistic metallic object, like a handmade rover (albeit one containing an ashtray), while around the space drifted an audiowork, Puck (2012), of a man with Down’s syndrome repeatedly essaying lines from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1596): “If we shadows have offended / think but this, and all is mended.” At the ICA, soundtracking the aforementioned Chess – which includes a cutout of Elvis Presley of the sort one might find in an old-fashioned movie theatre – Bacher set up a loop of Presley, Elvis (2009), singing the wordless falsetto outro of Blue Moon (1956). Here he’s a man who sounds like a woman; his voice merges with echoes of Duchamp. Everything melts, alloys.

Undergirding all the different trajectories and star maps of Bacher’s work, and working in tandem with its prolixity, is one broad stylistic approach: lowgrade, secondhand transmissions, second-and third-generation reproductions that accrete glitches, mixing signal and noise. The noise speaks as well as the signal – ‘one big ruin’, as Bacher describes her work in one interview – and slows the viewer as, say, listening to an old, hissy bootleg does. You strain to hear what’s there, and the listening is active: you might, indeed, be ‘hearing things’ that say as much about you as they do about the artist, just as the questions Bacher’s interviewers put to her in Do you love me? are inadvertent confessionals. The noise conveys in another way too. It says Bacher is an artist who simultaneously needs to speak and not speak – needs to do so through others, to smokescreen what she says. Hobbled communication is still communication. It’s the largest double, or binary, in a configuration of doubles that ranges from reapplied media images to double moons to black deserts and white ones, and collapses presence and absence into each other.

Bacher’s art is given life by her life’s unpredictability

This arrangement must also be reactive, lest it calcify. Bacher’s art is given life by her life’s unpredictability – eg, Huge Uterus (1989), a video recording her operation for fibroid tumours – and appears, at the time of writing, to have responded to her ascendant profile in the artworld by tossing out bedlam by the handful; the very procedure of making – overproducing – now becomes important. By the end of SNOW, Bacher seems to be making work constantly, without interrelation. The works are dated by day. On 23 March 2013 alone she makes Ft. Lauderdale, ‘a diving board-like structure out of aquamarine plastic panels’, The Thinker, a Rodinesque ‘sitting female mannequin’ and Cannibal Love Song, a red circle of folded and unfolded vinyl. As the outpouring continues through sculpture, performance, photography, video, it feels like one holistic, gnarly thing. Her sprawling website, lutzbacher.com, meanwhile, is as immersive as any actual net artist’s: not surprising for a figure who effectively predicts our collective disappearance behind avatars.

These recent pursuits, though consistently raw and anxious, admittedly don’t necessarily always contain Bacher’s semi-signature technical degradations. Rather, they allow flooding itself to become distortion. They still point, though, to messy signalling, and how that messiness can be – to echo a title she uses regularly – a ‘gift’. Objects and images, when roughed up, get enlarged, made galactic; they gain something by becoming, in music’s parlance, ‘lossy’. An artist’s public image is like that too. Subtracting information, Bacher has enlarged herself, pragmatically. Recognising the cult of personality that clings to artists, she’s made herself a personality in absentia, . la Warhol and Duchamp, a personality not reified but accepting that people are larger than any image put on them. There is a philosophy, too, of reception at work here. Recognising upfront that viewers never get a full picture, always inject their biases into whatever they see, Bacher doesn’t even try to present one; she offers something explicitly speckled with holes and gaps to occupy. In all of this, she creates something that allows for public fascination – call it mystique – that serves as a shield, that telescopes her most overt concerns. There is violence everywhere, her work implies as it brutalises images and objects and reveals brutality’s operations in the world, and it is a small violation within the larger ones, a disarming, to become the object of knowledge. So do I love her? I don’t even know her. But yes, I do.

This article originally appeared in the summer 2015 issue of ArtReview