There are, her performances suggest, a dozen ways of saying something – and a logic that exists beyond straightforward linguistic meaning

In 2012, during that year’s Glasgow International, I watched Sue Tompkins give a spoken-word performance at an offsite event in a pub. I don’t recall what she said – though in another recital from the same year that’s preserved online, she talks about broken noses, novels, ears bursting, settling differences via telephone, throbbing, wanting to run out – but I do remember the tumbling way she said it. I remember Tompkins repeated and glitched words and phrases, trying them on for size and mingling them with nonsense sounds, making language at once pliant and incantatory. I remember her casually tossing the sheets of paper she was sort-of reading from onto the floor as she went, also bouncing on her heels and pacing back and forth and up and down in confined space. As if her speech were a discomfiting current flowing through her, making her move hither and yon.

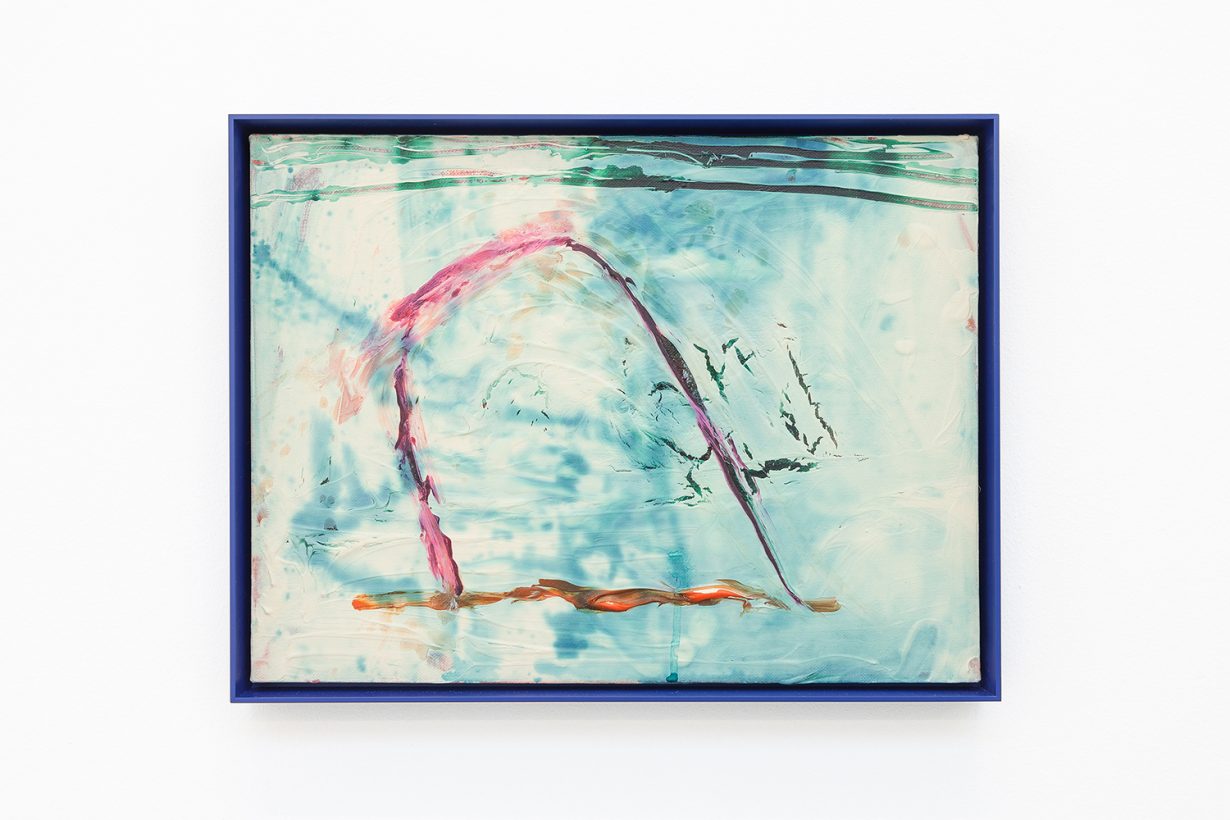

Mores, 2018, acrylic on canvas, aluminium frame, 42 × 32 × 4 cm (framed).

Courtesy the artist and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow

Most of all, Tompkins, smiley and sometimes just nodding her head as if counting beats until the next breathy outburst, materialised a contagious excitement, a kind of exultancy, at the endless affective possibilities of verbalisation. There are, her performances suggest, a dozen ways of saying something, anything, and a logic that exists beyond straightforward linguistic meaning. Her throat-clearing and rhythmic repetition of phonemes have a rightness and timing despite not signifying, like the verbal version of a jazz musician’s extended technique on their instrument. It’s poetry of a sort, Tompkins’s spoken-word, and partly indebted to the repetitions in some modernist forms (eg Gertrude Stein), but it is also transient sculpture, words hovering in the air like physical things, then swept aside. As the Glasgow performance ended, I wanted to congratulate her, but too much chatting and inhaling of secondhand smoke in recent days had incapacitated me. I scrawled ‘I’ve lost my voice’ on one palm and ‘You were great!’ on the other, crossed the small room and showed her my hands; in any case, the evening didn’t need any more talking.

Tompkins, who was born in Leighton Buzzard, England, but has lived in Glasgow ever since attending the city’s School of Art during the early-to-mid 1990s, is – or comes across as – a naturally magnetic performer, but her story both as an artist and as a musician is an utterly unlikely one. In the late 90s, while launching her art career after studying painting, she was the frontwoman for Life Without Buildings, a beloved and actually really good art-school band who released one great album, Any Other City (2001), of math rock-inflected, jangling and jangled post-punk topped with Tompkins’s ebulliently wired, speak-singing phrasemaking before splitting up. (Just to underscore this, most art-school bands are terrible, and there are vanishingly few examples of good ones whose members transition to successful visual-arts careers. Elizabeth Price, once of shambling indie band Talulah Gosh, is another rare exception.)

Tompkins didn’t want to be in the music world and hasn’t been back, aside from demonstrating how musical someone can be without music. Life Without Buildings’s live album, Live at the Annandale Hotel, recorded in Sydney, came out to fans’ near-disbelief in 2007, and that was pretty much that, or almost – aside from an unlikely recent twist recounted later in this text. It speaks to the band members’ apparently shared serenity with LWB being a thing of the past that I taught, for several years, alongside the band’s former bassist, the artist Chris Evans, and beyond mentioning that he played bass he never talked about music or mentioned their name. (The guitarist, Robert Dallas Gray – aka Robert Johnston – is a graphic designer and extant musician; the drummer, Will Bradley, a well-regarded writer and curator. “We did everything we set out to do,” he clarified to The Guardian earlier this year.) On the posthumous record, as the band expertly navigates all manner of twists and turns and lopsided time signatures, Tompkins is a palimpsest: she sounds at once giggly and nervy and self-assured and incredibly present and alive, as if the words were tumbling out of her unbidden in a half-directed flow; but if you compare the live and recorded versions, they’re extremely similar, a brilliant simulation of in-the-moment improv.

Tompkins understands that words have a situational gravity, and you see that in her paintings too. (Another very small category: the successful painter who’s also a performer, or vice versa.) Take, for example, All the Time (2018): that phrase, its letters daubed in a modulating range of colours from acidic lime through kid-friendly cerulean blue and shit-brown on a bile-coloured ground in a perky green frame, the ‘All’ doubly underlined. The non-language constituents, colour and gesture, serve as silent analogues for phrasing, such that the painting is at once sighing and determined. Here and elsewhere, Tompkins seems to pluck a phrase from the babble of the everyday and invest it with existential contours that belie the outward casualness of her facture. Sometimes this coming-into-focus, or giving weight to words, happens with delayed effect; the multi-panel Skype Wont Do (2013) has found its moment in the last year or so. Mores (2018), in which a letter hovering indecisively between a lower-case ‘i’ and a ‘j’ floats in an expanse of turbid orange before a mass of tangled blue brushwork that could be a forest, turns abstraction into charged personal drama with the addition of a single letter; at the same time, it’s kind of goofy.

Other works involve no language at all; some years back she was fond of pinning scraps of coloured chiffon, accoutred with variously opened and closed zips that Tompkins says relate to the process of making a decision, to the wall in a way that seems at once casual and just-so (albeit accompanying them with typed text pieces, such as Odyssey Pink, 2011). Some of her works present as sheer abstraction. Always, though, there’s a sense of Tompkins’s relationship to how language can work: the seemingly small utterance that, correctly handled, assumes scale. The apparently weightless thing that, it turns out, has heft. Appearing both casual and profound requires work, needless to say. It’s quite possible that Tompkins is a covert grafter, but you’d have to step past her work’s deceptively wrought strategies to see it.

At the end of last year, another piece of Tompkins’s past assumed – like the Skype painting – new significance. At the same time as a generation of British bands – among them Dry Cleaning, Squid, Black Country, New Road – have adopted the sprechgesang (speak-singing) that Tompkins so winningly aerated two decades ago (and, to be fair, that Mark E. Smith was no slouch at two decades before that), Life Without Buildings went viral on TikTok. Pushed along by a share from 90s-music- worshipping musician Beabadoobee, (mostly) young women started using 15 seconds of Life Without Building’s signature song The Leanover in their videos, miming to Tompkins’s tricksy, thoughts- being-born repetitions – “If I lose you, if I lose you, if I lose you / in the huh, the huh, the huh, mmm / If I, if I, if I, if I / B-b-b-baby”, etc – while showing off their heels, or applying makeup, or sitting in the back of a car, or cavorting with their girlfriends.

Tompkins, for her part, professed herself very happy with this youth-friendly development – which also, incidentally, hugely boosted the band’s Spotify streams, such that they’ll probably make at least £11.43 out of it – for what she saw as the sense of freedom the girls were feeling. ‘Everything is open and somehow seems incredibly sensitive and sincere and transparent at the same time,’ she told the music website Paste. Additionally, in a way it’s perfect that a band, and an artist, who’ve hymned the flux of meaning – how contextual it can be, how to redirect it – should be rediscovered in this way. And in a medium that requires work. You watch these kids and think that to get to that point, to master the singer’s own effusive spring rhythms, must have required a deceptive amount of practice. Tompkins understands the theatrical and emotional value of hiding the effort, that it’s more impressive to see the apparently throwaway become something in real time than it is to encounter self- serious, capital-A art and find it not having much to say. Yet the main thing I remember from that aforementioned Glasgow performance, honestly, is being in the presence of someone extremely alive, or who at least knew how to give that impression. This is, I suspect, part of what the TikTokers are feeling, partaking of, while they borrow Tompkins’s speech rhythms, and what they might take with them. A line from The Leanover that the kids don’t mime, but might internalise: “You can be me, swim”.