The latest exhibition at Hong Kong’s Para Site, Liquid Ground takes a critical look at the city’s ongoing land reclamation projects

Launched in 2018, Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam’s ‘Lantau Tomorrow Vision’ – a HK$624 billion development scheme proposed with the intention of solving Hong Kong’s housing crisis – has become a subject of much controversy. The project, which entails the construction of artificial islands near Lantau Island, aims at creating a new economic hub for the city by 2030. Critics of the scheme have highlighted the severity of the environmental damage it will cause, as well as condemning it as an example of reckless fiscal expenditure. At Para Site, however, it’s the inspiration for an exhibition (complete with a makeshift wooden structure that presumably represents the idea of an island), curated by Alvin Li and Junyuan Feng, that takes land reclamation as a point of departure to explore the aforementioned criticisms, all the while revealing various facets of the relationship between humans and nature – from reverence to ruination.

Courtesy the artists

Lantau Island inhabitants Royce Ng and Daisy Bisenieks, part of the artist-and-anthropologist duo Zheng Mahler, demonstrate the significance of local Lantau wildlife and sensory limits to the human experience with Bubalus bubalis 16 – 40,000Hz (2021). The mixed-media installation contains an intricately constructed sculpture, consisting of water rippling between two Chladni plates, serving as a visual representation of frequencies only water buffaloes (native to Lantau) can hear and that are essential for herd communication. Known as wetland landscapers or ‘terraformers’, the buffaloes were once used as agricultural labour in Lantau, later released into the wild, turning wasted farmland into a biodiverse wetland. The necessity of creating a visual rendering of a sonic capability beyond human capacity speaks to the limited scope of our anthropocentric view of the natural environment. Issues that, as the fate of Lantau is being determined, seem more pertinent than ever.

One of the most imposing installations, Lee Kai Chung’s Sea-sand Home (2021), elicits a revelatory irony. Here Lee discovers that sand for ‘Lantau Tomorrow Vision’ (and other reclamation projects in Hong Kong) is likely from Qinzhou, Guangxi, in mainland China. Further highlighting the environmental concerns of the curatorial premise, the work also prompts revelations about the larger geopolitical context. Human-size replicas of sand-mining storage towers and pipes rise above the gallery floor; at their base, an image of salt pans is projected over salt spilled out in heaps. While the title references the process of desalinating sea sand before it’s incorporated into construction materials, it also visualises the financialisation of land, at the cost of its extractionist relationship to water.

Another strong work by a newly formed collective, The Centre for Land Affairs, boldly takes on one of the most prominent developers and art patrons in the city, New World Development (NWD). A pair of pink rubber slippers lies on top of a magazine, the cover of which features The Pavilia Farm, a luxury residential venture by NWD. The slippers, among other found objects included in Installation 1: On Art and Developer Hegemony (2021), are from dispossessed villages on land that NWD was involved in purchasing. Taking an investigative approach, the collective displays NWD videos alongside government reports, town planning documents and photographs taken by drones documenting their methods of acquiring land. The wider point here concerns the use of art to legitimise commercial projects and, conversely, the extent to which art infrastructure depends on opportunities provided by these developers.

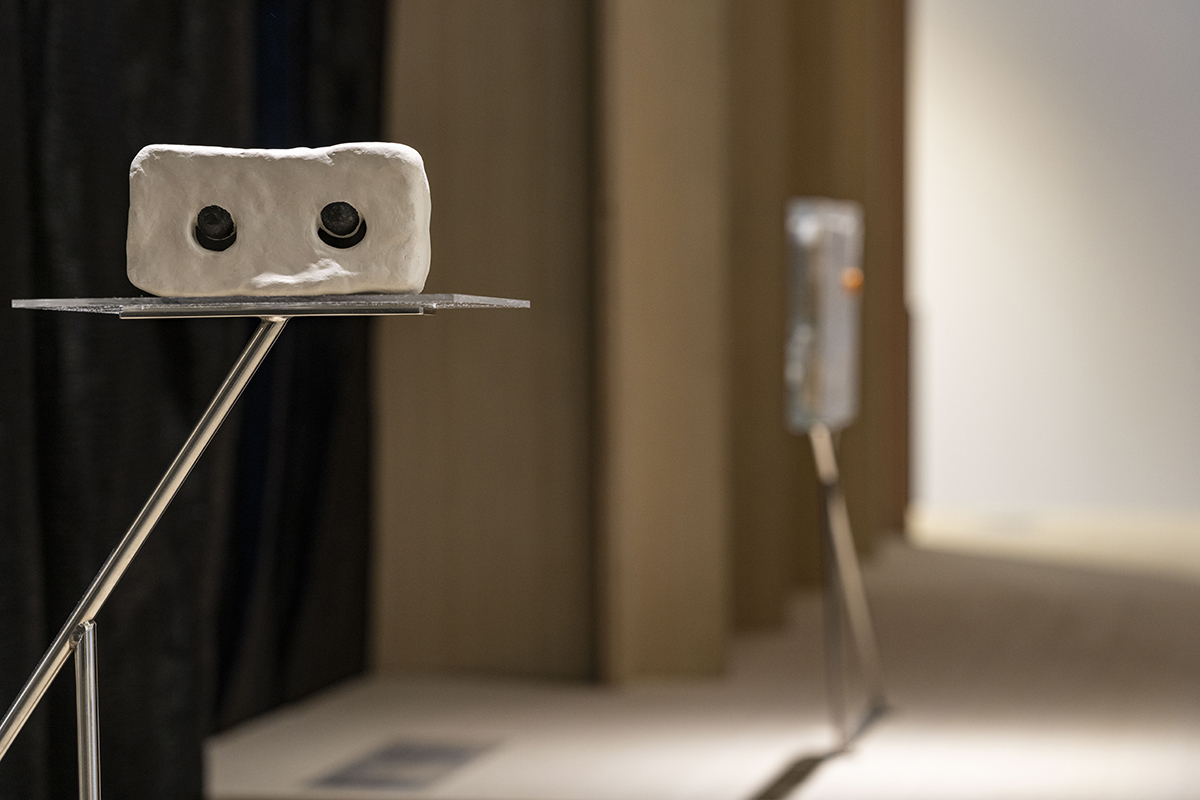

Beyond Hong Kong itself, Chinese mythology emerges as a common motif, most emphatically in work by Yi Xin Tong and a collaborative work between Future Host and Heidi Lau. Featuring sculptures (Petrified Sea: Aquatic Dragon and Rolling Eyes, both 2021) and a video (The Birth of Julung-julung: The Aquatic Dragon, 2019–20) that document Tong’s travels to the tourist-ridden Dinawan Island in Malaysia, the installation conjures the aquatic dragon Jiaolong to illustrate the artist’s own jaded frustration with Western erasure of Southeast Asia’s indigenous spiritual and ecological heritage. The small sculpture Rolling Eyes depicts eyes set in stone that appear to be rolling in an exasperated (but static) manner, echoing the artist’s own facial expressions in the video.

Heidi Lau’s Resentment Sleeve (2021) elicits a visceral reaction to the deceptive, grungy metal-chain-like appearance belying its ceramic consistency. Presented in conjunction with Future Host’s performance video Worlding Hands (2021), in which the artist choreographically reenacts a Chinese creation myth, in which a goddess made men by moulding yellow clay, Lau’s sculptures (The Fountain, 2021, in particular) visually mimic primordial ocean imagery loosely corresponding to the video. The main inspiration for the two works stems from Shanhaijing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas), a fourth-century BCE Chinese text that presents the mythological possibility of a world in which harmonious living among different species thrives. Here Shanhaijing’s creation myth is reimagined as a pathway to a truly sustainable future.

Overall, the exhibition presents thought-provoking and impactful works that grapple with complex, insightful ideas, with a compelling local (as well as a regional and global) resonance. Yet by comparison, the wooden island motif on and in which works are displayed seems a crude anchor and clumsy form of scenography. As the ‘Lantau Tomorrow Vision’ project unfolds amid unaffordable housing prices and developer monopolies that financialise land despite the effects of global warming and rising sea levels, there are lessons here to be learned.

Liquid Ground at Para Site, Hong Kong, 14 August – 14 November