Remember reading? Our editors have selected the books they’re coveting this summer. So pick one (or two; smartass), find a bench somewhere and get lost

All Fours by Miranda July

Canongate, 336pp. £20.

This isn’t anything so reductive as a midlife-crisis story, I know that, alright? But that’s the box I kept trying to stuff it into as I oohed, aahed, cackled, gasped and swooned my way through. All Fours wasn’t written for me, I know that too. I can’t believe I’ve even been allowed to read it, this bold, unfiltered story, full of observational wit, self-torture, obsession, longing, joy and… sweetness? Miranda July, in the fifty-first year of her life, is having a blockbuster summer, between the publication of this, her second novel, and the presentation of New Society, a retrospective covering three decades of the omni-artist’s performance, short film and installation works, at the Fondazione Prada in Milan. All Fours is narrated by a woman who sets out from LA on a cross-country drive, in part to refute her partner’s glib assessment that people can be divided into two categories, drivers and parkers, and that she, the narrator, who closely resembles July herself, is a parker (in it for the performance, the acclamation). She makes it as far as the next town over before, yes, parking in the forecourt of a motel, where she will hole up for the next three weeks. To say anything more would be an unwise attempt at containing the uncontainable. David Terrien

Cinema Love by Jiaming Tang

John Murray, 304pp. £16.99.

The movies playing on rotation at the Mawei City Workers’ Cinema – the venue in post-Socialist China at the heart of Jiaming Tang’s debut novel – are only wallpaper. Classic war films and supernatural cop dramas are merely the front, or facade, for a safe space where the gay clientele can cruise, or fall in love, without fear of judgement or public humiliation. ‘Within those walls exists a force that allows the hidden parts of people to be seen. Come alive,’ writes Tang. That force, however, soon comes up against formidable external ones. From the shadows of this shabby movie theatre quickly emerges a tender, compassionate story about parental expectations and Confucian values in 1980s China, and their impact on queer men, and the women who wed them: Cinema Love centres on a marriage of convenience between Old Second, a young patron, and Bao Mei, its box office ticket seller. Tang, a queer immigrant writer based in Brooklyn, follows them over several decades – shuttles us back and forth between rural China and New York’s Chinatown (which they emigrated to), between the fleeting joys of youth and the nagging regrets of old age – with the aim of chronicling the long-term fallout, for all involved, of forbidden love and sham marriages. And he succeeds, by distilling his big themes into small, crystalline moments of humour, infidelity and longing. Max Crosbie-Jones

Mina’s Matchbox by Yoko Ogawa

Harvill Secker, 288pp. £18.99.

Yoko Ogawa’s novels tend to be about memories. In The Memory Police (1994) – currently being adapted into a film by director Reed Morano and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman – memory is a site of policing and erasure. The story takes place on an island controlled by the titular institution, where the residents’ memory of objects like perfume, birds and even their own body parts would enigmatically disappear along with the items themselves. If memory is the anchor of existence, or permanence, to remember is the only way to survive. Originally published in 2006 and recently translated into English, Mina’s Matchbox’s take on memory is less politically charged, at least at first glance. For protagonist Tomoko, memories of childhood are that of a largely carefree neverland coloured by occasionally desperate escapist longing. She lives in a mansion in the countryside with her large German-Japanese family, who own a soft-drink company and have a hippo as their pet. But as we explore Tomoko’s childhood world, narrated with a certain naivety, we discover that it is no less riven by history and conflict than the present. (All of this plays out during an Olympic summer that takes place amid political violence.) It’s a timely if disconcerting reminder of all that swirls beneath seemingly placid water. Yuwen Jiang

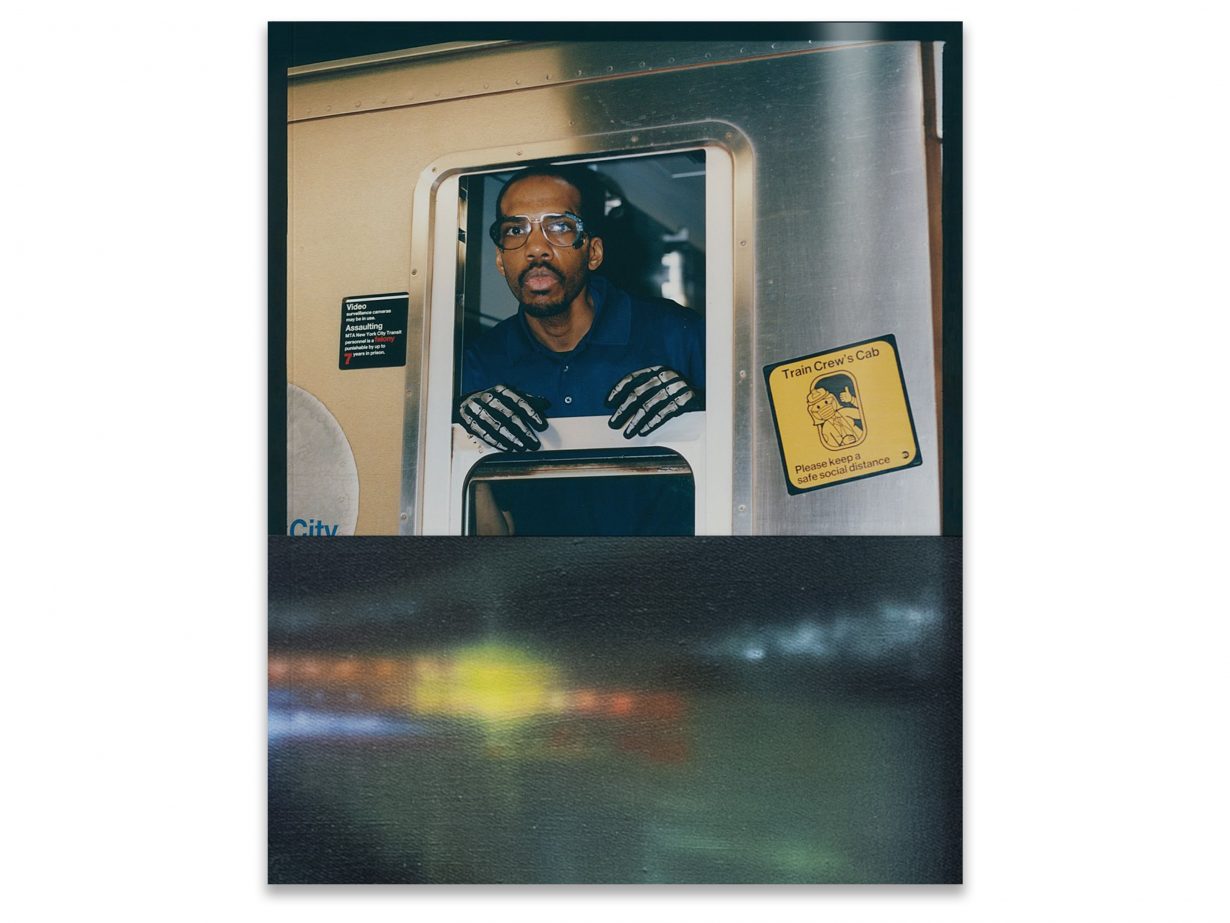

Subway Portraits by Sirui Ma

die Keure, 208pp.

The New York City subway is typically a place where staring is gauche and image capture of any kind is annoying. One may recall Chantal Akerman’s three-minute static shot inside the 1 train in News from Home (1977) and how the passengers in the frame begrudge and try to ignore the camera. In the UK-based photographer Sirui Ma’s new book, however, the subjects – MTA conductors – are shown looking, and at times even smiling, at the camera. Following Ma’s solo exhibition Little Things Mean a Lot at Hackney Gallery in London, which celebrated local Asian diaspora women, Subway Portraits focuses on the unsung workers who make the NYC subway system run. Featuring 60 portraits alongside contact sheets, an interview with a conductor, a text by Hua Hsu and additional artwork by Leon Xu, Subway Portraits places Ma among the likes of Walker Evans, Alen MacWeeney, Bruce Davidson and countless others who’ve commemorated this symbol of the city in photographs. Ma documents a range of characters who share an occupation but whose individual personalities shine through in the details: one driver wears black gloves with skeleton hands printed on them, another rocks fuchsia lipstick. Instead of wistful missed connections, Subway Portraits emphasises moments of recognition and acknowledgment amid the hustle and bustle. Jenny Wu

Moderate to Poor, Occasionally Good by Eley Williams

Fourth Estate, 208pp. £16.99

A ‘mountweazel’ is a decoy word, invented and deliberately inserted into a dictionary or encyclopaedia as a sneaky means of asserting copyright. Named after a fictitious personage included in the 1975 New Columbia Encyclopedia, there’s usually only one hidden in a given publication, as evidence if someone else copies all your hard work. Eley Williams’s previous book, The Liars Dictionary (2019) – her first novel – presented a young publishing intern struggling to both articulate her feelings (how do you describe the indescribable?) and to weed out a remarkable number of mountweazels secreted in a dictionary by a colleague 100 years earlier. Moderate to Poor, Occasionally Good is a welcome return for Williams, running again through the playground, as she is wont to do, of lexicographical loops and syntactical swings and roundabouts. This a collection of short stories, and Williams is a master of the form. (Her 2017 collection, Attrib., is a stone-cold classic. Go. Read.) With its promise of, among other characters, a wayward shipping-forecast announcer, a distracted courtroom sketch artist, and a distraught canned-laughter editor, I’m looking forward to losing myself in Williams’s labyrinthine and puckish love of language. Chris Fite-Wassilak

Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel by Yoko Tawada

Translated from German by Susan Bernofsky

New Directions, 144pp. USD$14.95

In 1993 the Berlin-based writer Yoko Tawada won the Akutagawa Prize for The Bridegroom Was a Dog, a novella about a quirky woman who runs a tutoring centre called the Kitamura school. There, strange things happen that make Miss Kitamura the subject of neighbourhood gossip – she is visited, for instance, by a suitor who appears to be a dog in a man’s body. Much has changed since Tawada wrote about this teacher, who seemed to have a stable job with no oversight despite ever-present rumours. Tawada depicts another kind of life of the mind in Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel, her 11th book to be translated into English. In this delirious novel, Patrik, or ‘the patient’, as he calls himself, is an ill and floundering early-career German literature scholar with a part-time position at a ‘stingy institution’ in Berlin. He is due to give a talk on the poetry collection Threadsuns (1968) by Paul Celan – his intellectual obsession, with whom he desperately over-identifies – at an academic conference in Paris. He just can’t seem to get there. In lieu of a canine lover, our contemporary hero communes with an ‘angel’ in a café (who may well be a figment of Celanian wordplay), driven to the edge by precarity and postpandemic anxiety. In comparison, the Kitamura school seems quaint. Jenny Wu