New on Netflix, Naoki Urasawa’s Pluto resonates in a world at war

Ah, Mont Blanc! Ah, Atom! Ah, Epsilon! Naoki Urasawa’s graphic thriller Pluto is crowded with fondly monikered, occasionally loveable and yet elusive and inscrutable automata whose complicated interior lives make for a vital techno-political parable of robot rights and android dreams.

Originally published in Japan’s Big Comic Magazine between 2003 and 2009, and later collected into eight deluxe English volumes by Viz Media, this lauded science fiction story has now been adapted by Studio M2 into an extraordinary animated series for Netflix. If you’re familiar with Urasawa’s reputation as the comics auteur behind sprawling conspiracy fables Monster (1994–2001) and 20th Century Boys (1999–2006), or with the frequent transubstantiation of comic books into anime exports that characterises Japan’s media industry, such news shouldn’t surprise. It’s Pluto’s unique relationship with its source material, however, that transforms this adaptation into a uniquely resonant artefact, one that seems to whisper its own techno-utopian codicils about the nature of reinterpretation and the life-giving ambition of animation itself.

Inspired by Osamu Tezuka’s The Greatest Robot on Earth, a comparatively simple tale of sparring robots serialised in Shōnen magazine between 1964–65 as part of Tezuka’s genre-defining Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy)series, Pluto features the lead character from a long renowned children’s comics classic. Named Atom, after the power source that gives him life, Astro Boy burst onto the international stage in 1952, a powerful robotic boy with an atomic heart who was built as a surrogate son for the mysterious AI expert Doctor Tenma after the death of his own child Tobio. As an agent of peace, and not necessarily of freedom, Atom’s adventures would help to rehabilitate the image of nuclear power in a postwar society recovering from the fallout of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan was working to tolerate an American occupation while anticipating an oncoming nuclear turning-point in which Japanese energy markets were newly opened to foreign interests as part of President Eisenhower’s ‘Atoms For Peace’ programme. Pluto inverts this utopianism, rebuilding Astro Boy into the protagonist of a geopolitical nightmare haunted heavily by the ‘War on Terror’ that began at the turn of the millennium. It’s this painfully ambiguous lineage, with the cherubic Astro recast as a potential weapon of mass destruction, that provides the timely political grit of Urasawa’s contemporary retelling.

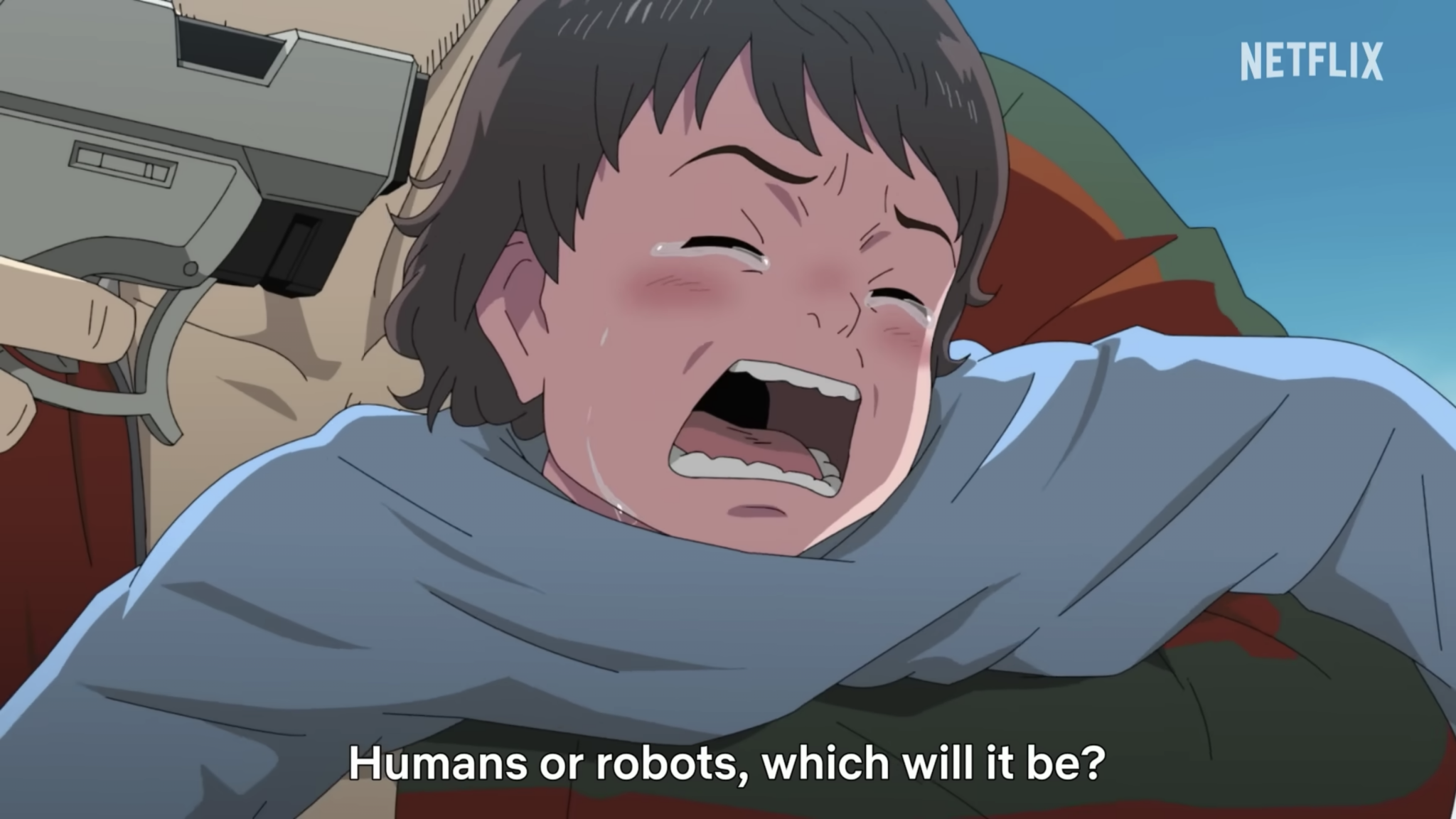

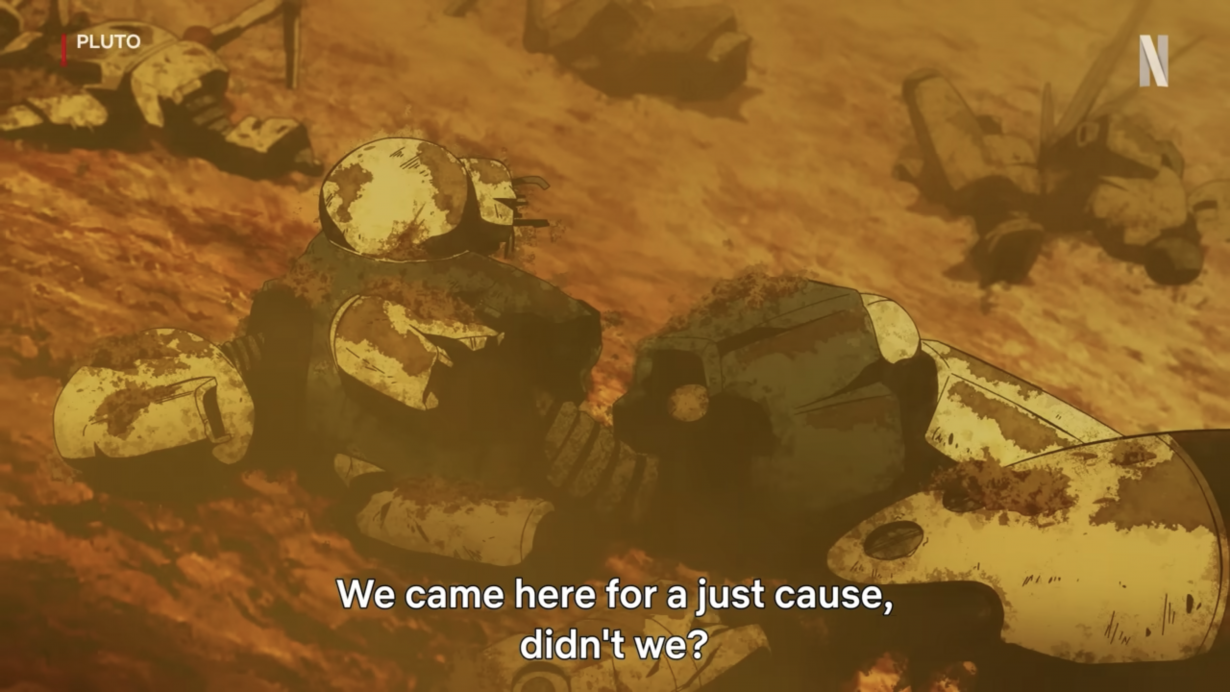

A near-future noir, Pluto recounts an investigation into the mysterious murders of the world’s most powerful robots and the (human) rights activists who helped ensure their liberty. Staged in a world still reeling from the 39th Central Persian War, a conflict initiated by the false accusation of a ‘stockpiling of robots of mass destruction’, the story imagines tensions between The United States of Thracia, Persia and the European Union. A robotic Europol agent works to uncover a vast anti-robot conspiracy while contending with the potential manipulation of his own memory, and the discovery that ‘hate’ has been introduced into artificial intelligences as a technique of individuation. Not only shadowed by the illegal wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Urasawa’s work also channels the deadening bureaucracy and political scapegoating of the scientific surveys that greased the tank tracks of Middle Eastern invasion: Pluto’s besieged scientists are caught in the grip of an opaque imperialism ghoulishly reminiscent of the circumstances that led to the 2003 suicide of the British weapons expert Dr. David Kelly, the government scientist who was part of the team writing the report on weapons of mass destruction used by the Blair government to justify the war with Iraq. Encountering the story in 2023, it’s chilling to realise that any intimation of ‘wiped memories’ and ‘erased hard discs’ might find uneasy biological analogues in an almost amnesiac normalisation of European and American interventionism.

Studio M2’s animated adaptation thus becomes an opportunity for recognising influence, innovation and the charge of allegorical horror across multiple tiers and temporalities of reinterpretation. It becomes a timely parable of intolerance and the impasses of hate handed down from Tezuka, through Urasawa, to the team of contemporary animators breathing new life into the story.

Despite Astro Boy’s adolescent audience, destruction and dismemberment weren’t unfamiliar motifs for Tezuka: MW (1976–78) was a libidinal tale of chemical warfare, while Dororo (1967–68) concerned a disembodied ronin searching for his missing limbs, both of which would find dark echoes in Urasawa’s reimagining, and further sensory impact in Pluto’s cartoon form. Tezuka was a lifelong ‘bug fanatic’ who notoriously infused his works with invertebrate metaphors, but The Greatest Robot’s androids don’t bear any of these arthropod influences. And yet Urasawa endows the robots of Pluto with clearly insectoid poise, the story’s namesake sporting an obsidian carapace reminiscent of an osamushi, Tezuka’s favourite beetle. There are also anticipations of our own viral robot megastars here: Boston Dynamics’ ‘Spot’ and Honda’s tragic ‘Asimo’ could have stepped, albeit unsteadily, from Urasawa’s world, robot celebrities that carry their own cautionary charge as much-mocked envoys from a world still hostile to the non-human.

The original Pluto manga undoubtedly handles some key plot points more effectively than its Netflix anime offspring. Our initial encounter with Brau 1589, the first robot ever to have disobeyed his protocols and murdered a human being, takes place in the dimly lit basement of a correctional facility, the terminal stillness of which is uniquely enhanced by the artist’s deftly technical and disquietingly noiseless monochromatic panels, offering a graven enclave for our ghastly comprehension that the still-sentient remnants of this broken machine might’ve experienced something akin to pleasure in its actions. Other sequences, however, truly dazzle in animated form. In the comic book, the holographic invocation of a crime scene in a police VR lab lurches with procedural dullness; in M2’s adaptation, the scene is neon-rendered into an exquisite visualisation of advanced investigative infrastructure, the fractured beams of a ryokan and the curiously discarded remnants of a tea ceremony materialising as incandescent evidence upon a laboratory floor.

‘What starts as imitation soon becomes real’, muses Doctor Tenma in Urasawa’s Pluto, observing the uncanny learning capacities of artificial intelligences. It’s a mantra that carries a disquieting resonance while watching Netflix’s adaptation:fundamentally, Pluto aims to be a morally instructive work about human agency and the longing to construct a more peaceful and equitable world. It’s without doubt a continuation, albeit secularly rephrased, of a Buddhist-inflected concern of Tezuka’s own life-long project to understand the human desire to seed new life into the world while simultaneously devaluing life through acts of intolerance and warfare. For the science fiction writer Ada Palmer, such acts of philosophically motivated animation were ultimately redemptive for Tezuka, ‘part of the creative instinct which was the only thing that made our warlike race forgivable’.

But what use is a parable we don’t learn from? With artillery smoke blossoming from Gaza and Odesa, and the not-so-veiled pronouncements of nuclear antagonism chilling the mediasphere, it’s difficult to square Urasawa’s reinterpretation of Astro Boy with anything akin to redemption while Tenma’s notion of imitation becomes all the more pressing, agonising, hopeless. Perhaps this is where we find Pluto’s timeless provocation. Do we simply replicate the language of hatred like pre-programmed automata, or work to disentangle our chaotic circuitries of cultural, technological and industrial inheritance in the hope that we might find new ways of being together?

Jamie Sutcliffe is a writer, curator and codirector of Strange Attractor Press.