How does the artist, representing Singapore at the 60th Venice Biennale, explore and challenge what we perceive as real and fictional?

Back in 2017, a relatively anonymous two-storey terraced house on a residential estate in Singapore constructed during the mid-1960s to house British military personnel was home to an archaic-looking museological display. It featured glass cabinets and items ‘archived’ on shelves and tables, with more than 300 objects, artefacts and photographs spanning from Singapore’s colonial past to the present day. There was no guide to the exhibition, just an 80-page dossier of seemingly randomly selected numbered reports, drawings, diagrams and photographs.

Titled The Bizarre Honour, an anagram of the name of the artist who created it, Robert Zhao Renhui, the exhibition was organised under the auspices of the semifictional institute he established in 2008. Called the Institute of Critical Zoologists, it ‘aims to develop a critical approach to the zoological gaze, or how humans view animals’, by pursuing ‘creative, interdisciplinary research that includes perspectives typically ignored by animal studies, such as aesthetics; and to advance unconventional, even radical, means of understanding human and animal relations’.

The sheets in that dossier were bunched together in paperclipped clusters, such that more-or-less-related narratives morphed into each other. One such cluster, for example, moves from indigenous felines, to domestic cats, to wild tigers, to colonial wildlife exterminations and contemporary government regulations on pet-keeping. These were numbered in such a way that implied a much vaster archive addressing such subjects as the vexed question of how many actual tigers once lived in Singapore (while colonial reports seemed to indicate the island was infested with them, natural science suggests that it couldn’t support more than one).

The dossier also included ‘A Guide to the Birds of Chinatown’, featuring an index of popular dishes made from chickens and ducks), and instructions on how to build a reservoir, accompanied by a list of ‘unnatural’ lakes in Singapore. Presented in an archival box, it was the kind of thing that looked like it had been hurriedly scraped off a librarian’s desk. What the dossier highlights, however, are themes that will be picked up in Zhao’s display, Seeing Forest, in the Singapore Pavilion at the upcoming Venice Biennale: the way that humans seek to organise and categorise and the way in which nature constantly eludes such convenient pigeonholing.

The ‘museum’ itself was part wunderkammer (as it mixed the aesthetics of science – insect traps, skeletons, taxidermy, soil samples – with fantastical news articles documenting animal attacks and trees that housed ghosts), part colonial display (in the sense that it seemed to be a haphazard index of the flora and fauna of Singapore, peppered with a number of photographs of colonial types), and part hobbyist’s treasure trove.

In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe they were a space in which the rich, the powerful, or the ennobled could set up displays of nature’s laws to be observed and its aberrations studied: a space for the display of botanical and animal accumulation (regardless of natural environment and habitat) and new species ‘invented’ by the stitching together, in a Frankensteinian manner, of multiple animal parts. And the owners of these museums-cum-freakshows combined that with works of art, mechanical ingenuity and scientific wonders in such a way that natural and human invention might be regarded as on the same level.

In addition to the above and some potted tropical plants, the exhibition included fake fragments of the Singapore Stone, a sandstone slab thought to date from sometime between the tenth and thirteenth centuries CE that once stood at the mouth of the Singapore River. Covered in untranslatable writing, the object was believed by many to be related to various local strongman legends (of the kind in which stones are thrown to prove dominance and power). It was blown up during the mid-eighteenth century by the British to widen the waterway, so as to make space for a fort and its commander’s residence.

The original site of the stone now houses Singapore’s national symbol, the Merlion, a creature that fuses the body of a fish with the head of a lion. Though it gives Singapore its name (the Malay word singa means lion), the ‘king of the beasts’ is not indigenous to Singapore.

Like the Merlion, the artistic practice of Zhao often explores a blend of fact, fiction and history that revolves around the relationship between humans and nature, as well as the toll that the progress of the former extracts from the latter, standing as a record of the ways in which nature adapts to escape the classifications and mastery of humans.

Other projects by Zhao have included video explorations of Singapore’s ‘forgotten’ rivers that have been covered over in the name of urban development, but still comprise their own ecosystems (Trying to Remember A River; 2022); The Lines We Draw (2019–21) investigates the migrant sites of birds; his artist book and the accompanying exhibition, Singapore, Very Old Tree (2015) documents the relationships, memories and stories that the nation’s citizens associated with individual (and needless to say, old) trees in an attempt to make Singapore’s moniker, ‘The Garden City’, less anonymous and more personal; New Forest, New Worlds (2022) explores the city-state’s secondary forests and the impact of deforestation.

More recent works, such as the photographic series Singapore Crocodile, 1930s (2023), examine the truth values of photography and the relationship of that to our perception of history, with reference both to colonial records, the advent of AI and, more specifically, the capture of Singapore’s last crocodile.

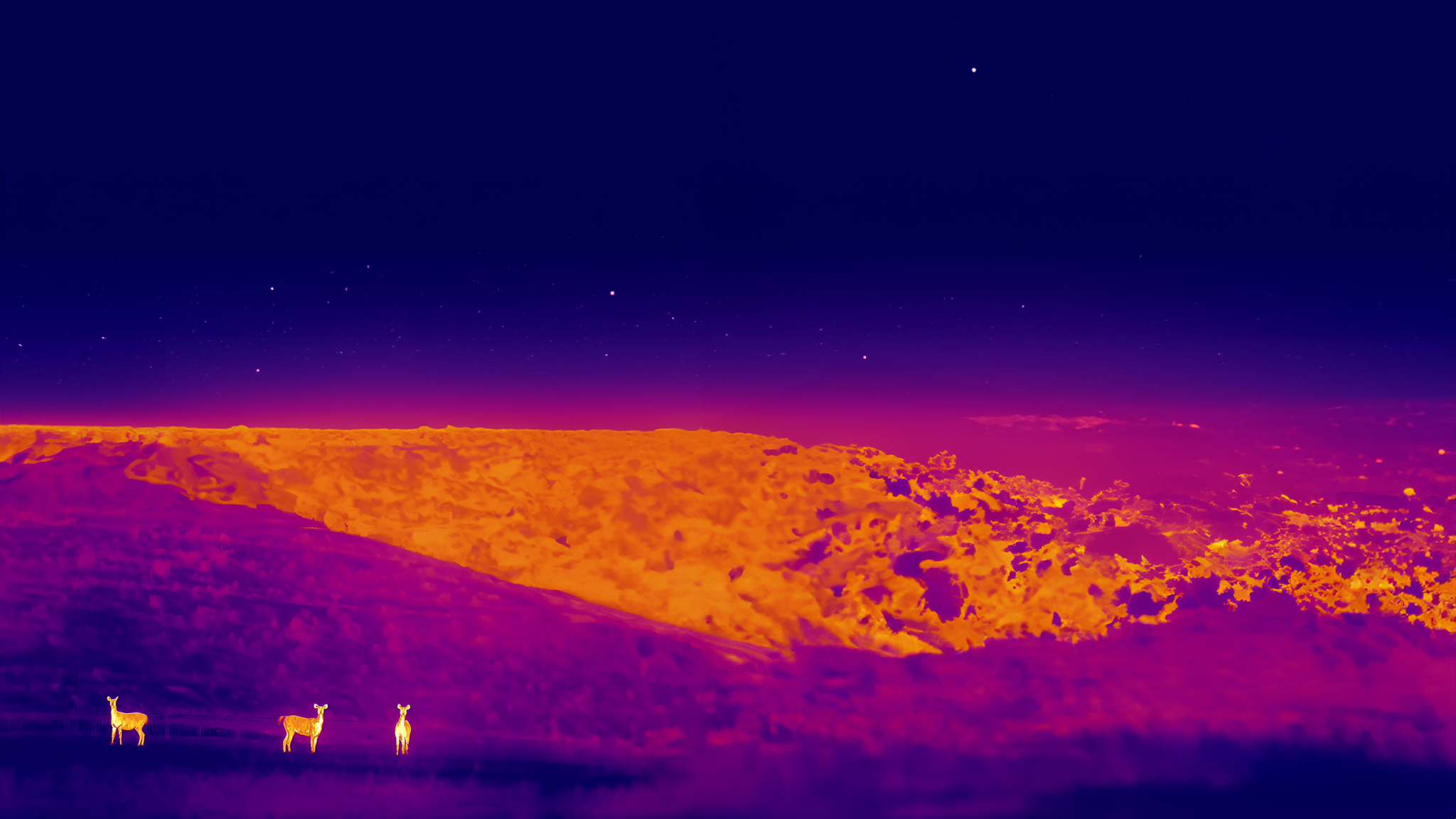

At the upcoming 60th Venice Biennale, Zhao will extend some of his earlier themes; the exhibition will feature three key works inspired by the secondary forests that have grown naturally over land previously subject to human activity.

One work in particular offers an ongoing dialogue with his preoccupation with contested histories – both scientific and historical – via a sculptural video installation, a sort of dismantled wunderkammer constructed from a wood species native to the region. Showcasing screens featuring films of various creatures that have adapted to this transitory space between urban development and ‘virgin jungle’, it alludes to colonial systems of classification while destabilising control over natural-history narratives – an imaginative cabinet of curiosities that draws out relationships and networks that explore the limits of human agency, the tensions between control and a lack of it.

Perhaps a focus on these themes is to be expected given that Zhao was born and is based in a country that (more than most) was half discovered, half invented, both by colonial powers and the postcolonial city-state. In the time between gaining independence in 1965 and 2015, Singapore increased its landmass through artificial reclamation from the sea by 22 percent, with a further 8 percent projected by 2030. Its population has also almost tripled during that period, from two million to almost six million in 2023.

As Zhao puts it, ‘the relationship between animals and humans has reached an appalling state’, where animals are visually exploited in zoos and museums, or exploited and sold as commodities for use in traditional medicines, among other things, including the marketing of idealised nature or the eradication of species we consider unimportant.

Yet, in Singapore, jungle fowl still roam the grass around social housing blocks, otters populate (or infest, depending on your point of view) the rivers and the streets. Life there is a constant negotiation. As is history: always contingent, always a negotiation between the contexts and imperatives of both the past and the present.

What Zhao’s work demonstrates is that we need to keep our eyes open, our minds questioning, and that within all this there is still some room for hope.

Commissioned by National Arts Council, Singapore, and organised by Singapore Art Museum, Seeing Forest will be presented at the Singapore Pavilion on the second floor of the Arsenale’s Sale d’Armi building from 20 April to 24 November 2024.