Virtual art in a virtual space – is the genre finally getting real?

For this critic, one of the few unexpected pleasures of life in lockdown has been exploring art exhibitions presented through VR. As I’ve argued, the VR exhibition reminds us to celebrate the value of material artworks and the freedom to encounter them in public space, while opening us up to the reality of art venues far away. Moreover, some artists are already investigating the paradoxes and the ironies thrown up by the situation of shows that no one can visit IRL, and the character of VR technology itself: John Armleder and Rob Pruitt’s recent show for Massimo De Carlo’s VirtualSpace allowed one to walk round a synthetically created (rather than photographed and scanned) space in which their work was exhibited, while having to negotiate the potted plants that occupied some of the gallery space, and perhaps wondering why Pruitt has arranged his set of elegant salvaged chairs covered in gold tape (Chairs, all 2019) on another side of the gallery. Who needs to sit down in virtual space, after all?

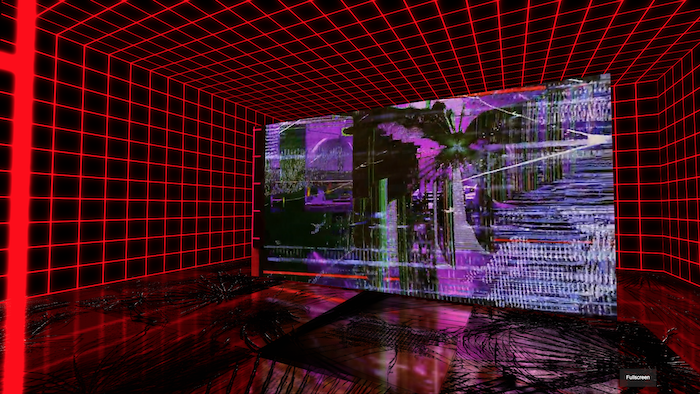

Things get more strangely complicated, though, when digital art – a strand of contemporary art with an ambiguous relationship to gallery space at the best of times – goes into a virtual space. One of the more haunting VR shows currently online is Chris Dorland’s FLR-13, on East London gallery Nicoletti Contemporary’s website. A series of interlinked CGI rooms, dark but for the glow of the red-neon wireframe grids that make up the ‘spaces’ (mapped from Nicoletti’s actual Vyner Street gallery space, according to the press notes), are host to ‘screens’ that are themselves showing what we might take as ‘videoworks’. FLR-13 refers to the 13th floor of highrises, which is often omitted as a numbered floor in some of the world’s more superstitious cultures (in which 13 is an unlucky number – other numbers for other cultures). Hidden, alternate-reality floors of buildings have a long pedigree of pop-cultural paranoia since at least The Twilight Zone episode The After Hours(1960). At Nicoletti, Dorland’s ‘video artworks’ exist in this alternate-reality space – the gallery but not the gallery, and parallel a series of other works we see were exhibited in Dorland’s accompanying real-life exhibition Active User, which opened in January and closed with the lockdown.

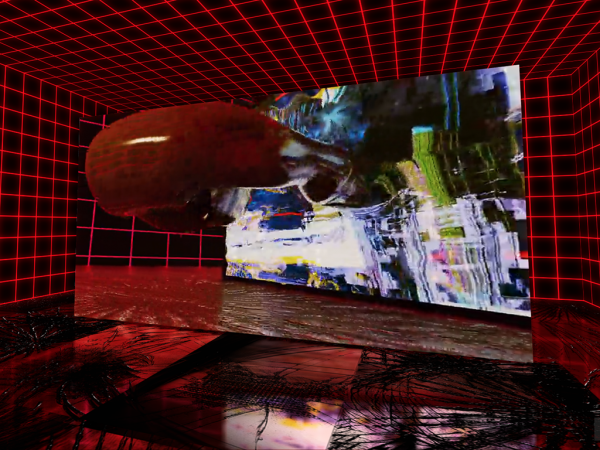

Dorland’s video sequences are shifting, flickering, stuttering collages of visual glitch – in the first space we ‘enter’ we see broken fields of algorithmic noise that then morph into more liquid, viscous forms, glistening like haemoglobin. Turning into the main space is another, bigger, room-dividing screen showing a denser and more complex sequence. Dorland adds to the disorientation by staging these sequences as if they were seen on a screen in a space identical to the one we’re in; as the point of view moves away and circles them, we see the shiny reflective floor (full of dark, glasslike fracture-lines) and the gridded walls that surround them.

If we’re in any doubt that Dorland is messing with our sense of place and corporeality, the work on the main screen pushes this question to a grotesque, absurd conclusion – as we watch the circling sequence of the screen that is the space we’re already (virtually) in, a weird amoebalike substance distends out of the screen’s ‘surface’. This liquid projects through both sides of the zero-thickness screen in the depicted space but doesn’t penetrate ‘our’ space. It is not a pleasant experience, a queasy nightmare with retro echoes of early VR-obsessed films The Matrix (1999) and Lawnmower Man (1992).

Dorland’s notes refer to the show’s inspiration in the work of novelist Philip K. Dick, and FLR-13 is something of a homage to Dick’s deeply paranoid vision of how contemporary society and technology were on course to disintegrate the fragile distinctions between subjectivity, the body and reality. Its spectacle of infinite regress isn’t just about collapsing the material and the virtual, but a more disconcerting reflection on who it is that is doing the seeing, and where we (or they) are. In Dick’s extraordinary novel A Scanner Darkly (1974), the protagonist, a druggy dropout who is also an undercover cop charged with investigating the drug trade, can monitor his housemates remotely, wears a camouflage suit that disguises his identity and eventually splits his personality into two different individuals under the influence of the drug he’s investigating. Those anxieties seem refracted in FLR-13. Shut in during the lockdown, one’s idea of real life, of a world going on ‘out there’, becomes swallowed up by the almost all-encompassing power of the screen, since experiencing it and acting in it are reduced to little more than reacting to news and social media. It’s a world Dick would have recognised. With horror.

Chris Dorland, FLR-13, Nicoletti Digital, 10 January –