Their artworks – on view in New York this summer – disorganize the ways of seeing and knowing that are the inheritance of colonial modernity

The paintings of Shahzia Sikander and Julie Mehretu are rarely spoken about in the same breath. Indeed, a cursory glance at their work seems only to confirm their differences. Most obviously, there is the disjuncture of scale: Mehretu’s paintings are massive, all-encompassing works that threaten to engulf the viewer with their sheer immensity and dizzying detail. Sikander, in marked contrast, is famously trained in the exacting art of Indo-Persian miniature painting, and her early work is, as she has put it, intensely ‘quiet [and] small’. Then there is Mehretu’s deep commitment to the language of abstraction, as opposed to Sikander’s decades-long exploration of the traditional idiom of the miniature, replete with human and nonhuman figures. Furthermore, Mehretu’s early interest in capturing ‘a spatial history of global capitalism’ could not seem further removed from Sikander’s early concerns with rupturing the gendered interior spaces of the domestic.

Yet major exhibitions of both artists in New York City this summer – a survey of Sikander’s early work, from 1987 to 2003, at the Morgan Library & Museum, and an expansive midcareer retrospective of Mehretu’s work, from 1996 to 2019, at the Whitney Museum of American Art – allow for a different apprehension of each of these remarkable artists when seen in relation to one another. Placing their work in the same frame reveals their ‘queer affinities’. I use ‘queer’ here in the sense of ‘odd’ or ‘strange’, but also to reference both non-normative gender embodiments and sexual desires that their paintings conjure forth, as well as an alternative way of seeing – a queer optic – that their work enables. This queer optic brings to the fore the intimacies of multiple times, spaces, art-historical traditions, bodies, desires and subjectivities. Situating the work of Mehretu and Sikander in relation to these different senses of queerness illuminates their affinities, both formally and conceptually.

on wasli paper, 43 x 31 cm. © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York

Sikander and Mehretu have intersecting life trajectories. Both were shaped by personal and collective histories of war, militarism and diasporic dislocation that mark their work in ways both subtle and overt. Sikander was born and raised in Lahore, before relocating to the us to attend the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 1993; Mehretu was born in Addis Ababa, before her family was forced to flee, in 1977, eventually settling in Michigan. Sikander and Mehretu were part of the same cohort of feminist artists of colour (which included Kara Walker) trained at RISD during the mid-1990s. After RISD, Sikander moved to Houston to take part in the Core Fellowship Program at the Glassell School of Art, where she worked with Rick Lowe of the community arts nonprofit Project Row Houses in the Third Ward, one of the city’s oldest Black neighbourhoods.

Mehretu made the same journey a few years later, and credits Sikander with paving the way for her. The time in Houston was formative for both artists, and they brought that spirit of collaborative engagement with them to New York City during the late 1990s, a moment when queer and feminist diasporic communities of colour were boldly laying claim to the city through their art and activism. Mehretu recalls the outward-looking, cosmopolitan internationalism of that historical moment just prior to 9/11, and her affinity with other artists who were not bound by nationalist ideologies, while Sikander remembers its ‘porosity’, a time defined by an ethos of openness and collaboration. Indeed Sikander, in the role of curator, included Mehretu’s work in a group show at Exit Art in 1999, the first time that Mehretu’s work was shown in New York City. Curiously, however, Mehretu is typically framed as a singular figure ‘almost without generational referents or peers’ (as Whitney curator Rujeko Hockley writes; the Whitney’s fine catalogue attempts a corrective by situating her within a genealogy of Black abstraction). The same is true for Sikander, which may well be due to her status as the first artist to inaugurate what is now known as the ‘contemporary neo-miniature’. What such framings of both artists elide is their deep investment from the beginning of their careers in creating and sustaining collective artistic and political communities, which included not only their ties to one another but a wide network of queer of colour, feminist and diasporic artists, scholars and activists.

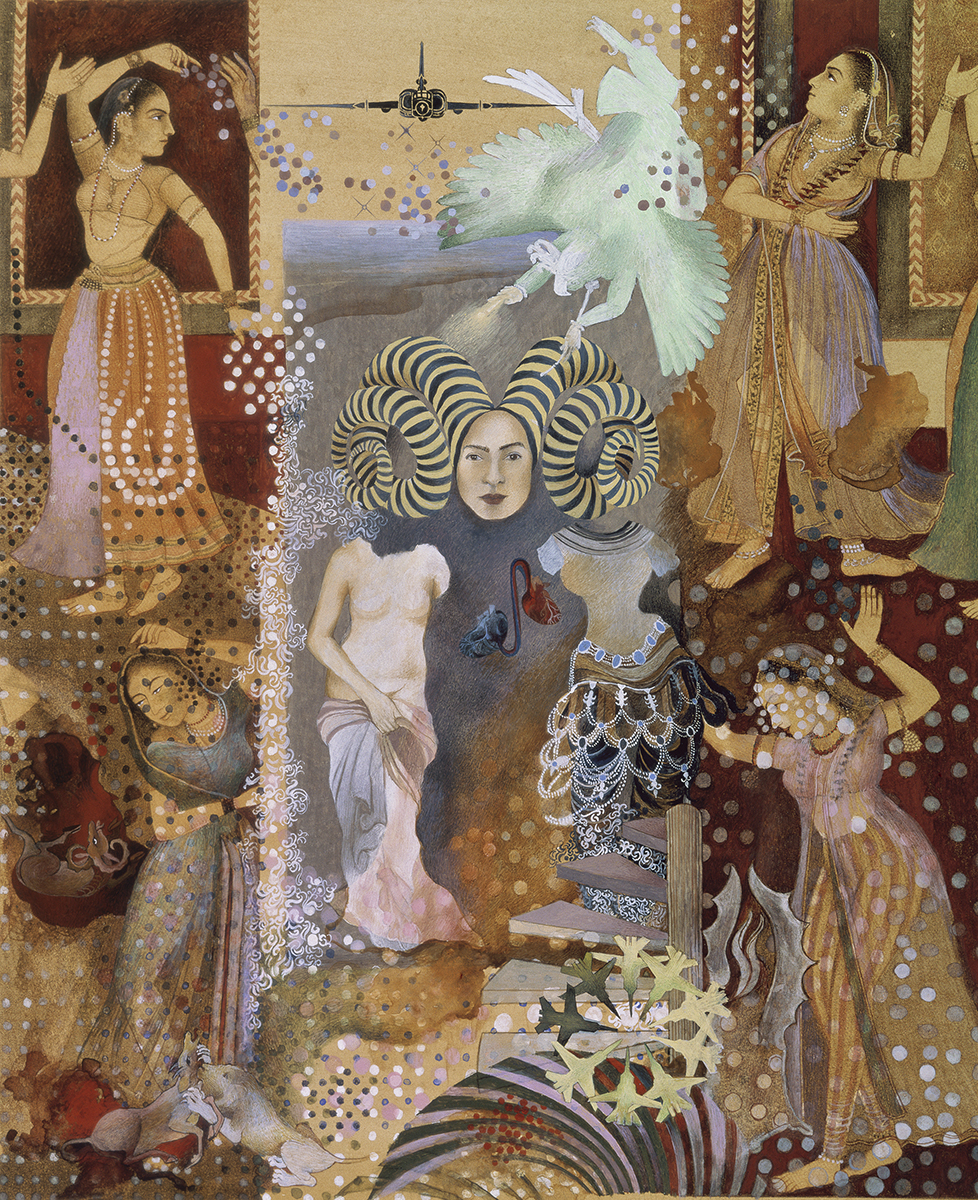

The works of both Sikander and Mehretu instantiate a queer optic, one that disorganises the ways of seeing and knowing that are the inheritance of colonial modernity. Visitors to Extraordinary Realities: Shahzia Sikander at the Morgan are greeted by an arresting bronze sculpture, Promiscuous Intimacies (2020), placed just outside the gallery entrance. This is Sikander’s most recent work, and initially appears to be an anomaly: the rest of the exhibition is tightly focused on the first 15 years of Sikander’s career, providing a closeup view of her experiments with deconstructing and radically transforming the language and generic conventions of Indo-Persian miniature painting. While her work after 2003 increasingly turns to largescale formats, mosaic and digital animation, Promiscuous Intimacies is her sole foray into sculpture. But, in fact, the sculpture outside the gallery provides an indispensable entry point into the earlier work exhibited inside the gallery. It sharpens our vision to see through an optic that brings the queerness of Sikander’s early work to the fore.

The sculpture depicts two figures of archetypal femininity from different art-historical traditions, sinuously intertwined: an Indian Devata figure from the eleventh century balances upon and gazes down towards the figure of a Graeco-Roman Venus modelled on Agnolo Bronzino’s painting An Allegory with Venus and Cupid (c. 1545). Their interconnected bodies and gazes evince an unmistakably desiring, sensuous, erotic relation between the two figures. Sikander thus excavates the art-historical archive and transforms it into a queer archive. This is a central motif that can be traced throughout Sikander’s oeuvre.

the artist and Sean Kelly, New York.

As is evident from the paintings in the exhibition, such as Venus’s Wonderland (1995) or Sly Offering (2001), Sikander consistently brings together seemingly disconnected historical traditions and unearths the resonances between them through queer desire and embodiment. Indeed, we can understand Sikander herself as a curator in the sense that she places these different art-historical traditions in intimate relation to make apparent the impossibility of their discreteness. Sikander’s bold yet delicate evocations of radical relationality – our irrevocably intertwined, interdependent connection to the Other across time and space – find unexpected resonance in the largescale paintings of Julie Mehretu.

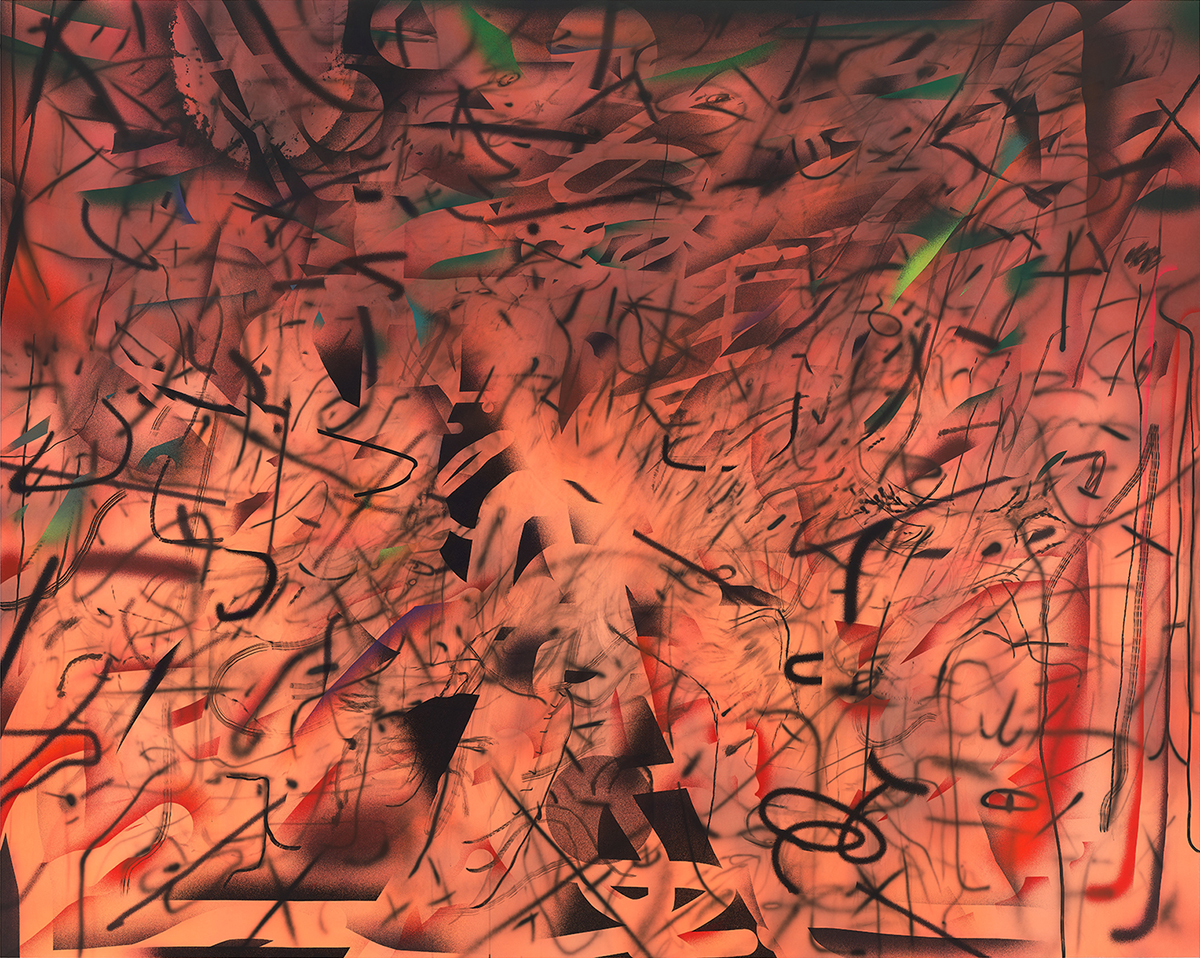

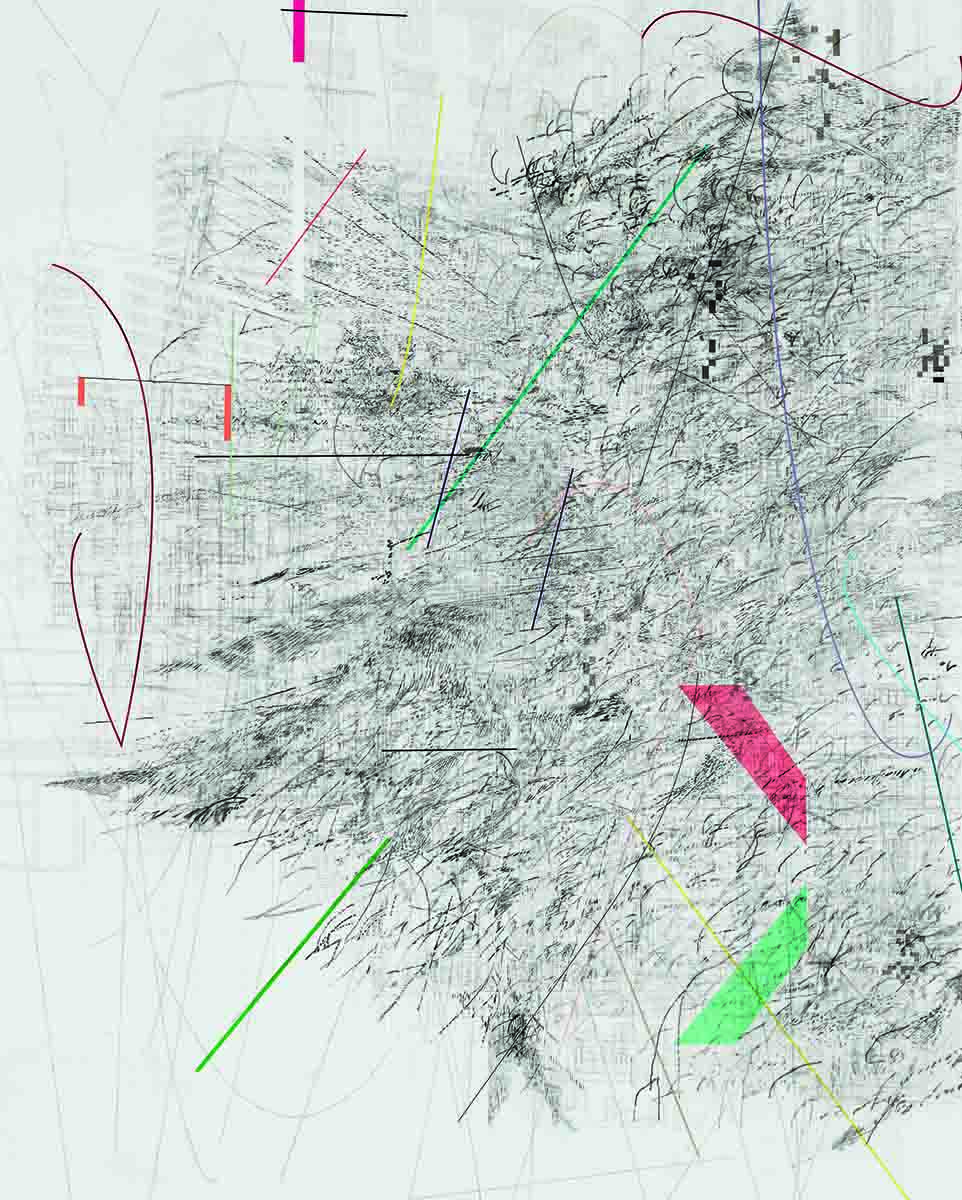

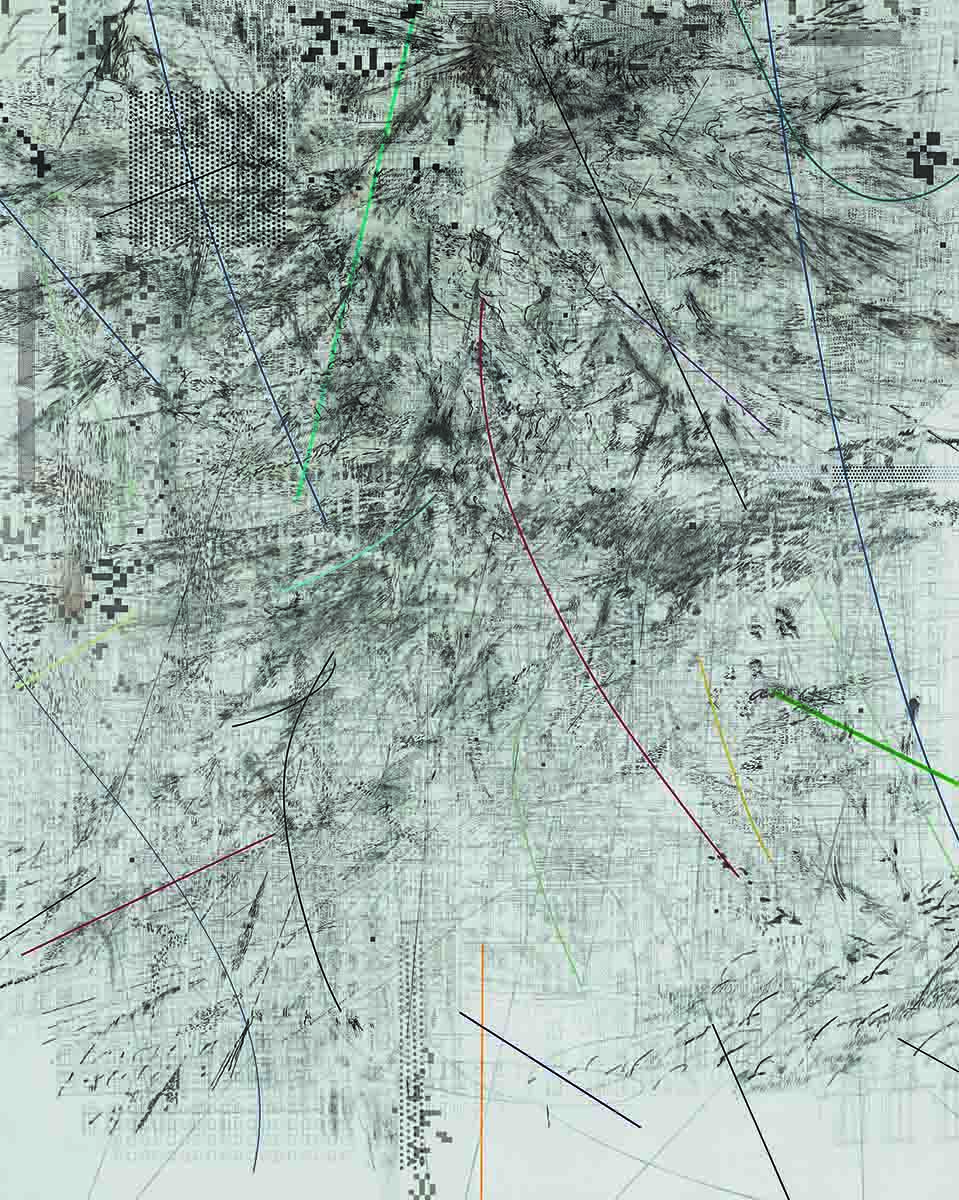

Sikander’s and Mehretu’s experiments with scale create palimpsestic landscapes that layer multiple times and spaces upon one another. Despite using very different visual vocabularies and idioms, they share a core commitment to drawing, to the black line and the gestural mark. In Sikander’s work, the mark moves seamlessly between figuration and abstraction: in her digital animation SpiNN (2003), for instance, the hair of female figures detaches from their heads, transforming into flocks of angry birds and into an indistinguishable, obscuring black mass. In Mehretu’s paintings, ‘the entirety of her formal language has been constructed with the black mark… the ever-present, anchoring black line’, which in later work is ‘transformed into the void of the black blur’, writes Adrienne Edwards, also in the Whitney volume. Mehretu has commented to me that she puts the language of abstraction “into a very big global perspective”, which leads to “a very different conversation”, given that, in the artworld, abstraction has been primarily associated with white male artists.

This is particularly apparent in her monumental architectural meditations on state power, such as Cairo (2013). These paintings allude to the residue of colonial techniques of ordering and surveilling space that mark postcolonial sites. In her astounding four-panel series Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts) (2012), for instance, a delicate filigree of architectural drawings of cityscapes that evoke various spaces of revolution and counterrevolution (from Cairo’s Tahrir Square to Mexico City’s Zócalo to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square and beyond) is overlaid with a dizzying array of cross-cutting lines, marks, shapes, gestures, shadows and smudges. To experience these paintings as a viewer is to be overcome with the impossibility of taking it all in. Their epic scale and the impression they give of ferocious movement and velocity are radically disorienting. They stop you in your tracks and demand that you pay close attention to their details, layers and fragments in order to attempt to apprehend their totality. As Mehretu’s response to the Arab Spring uprisings, the Mogamma series speaks to both the promises and failures of revolutionary visions of transformation. They suggest that the space of chaos, destruction and disorder may also hold lines of flight, potential and possibility.

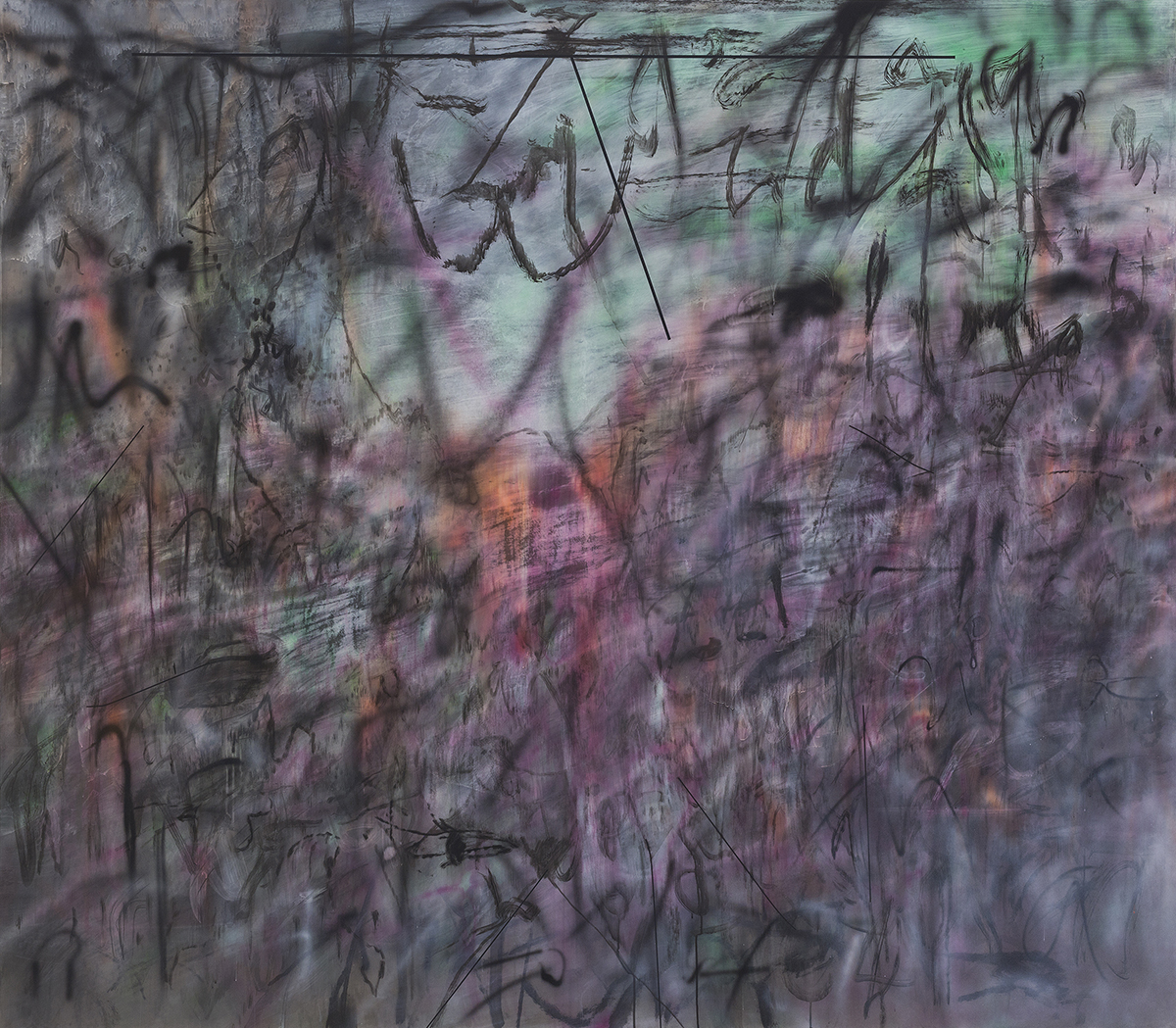

This sense of potentiality is evident in Mehretu’s subsequent work as well. In Conjured Parts (eye), Ferguson (2016), for instance, Mehretu leaves behind architectural drawing and instead utilises a mass-media image of riot police and protesters in Ferguson, Missouri, in the aftermath of the fatal shooting of Michael Brown. The photograph is blurred, distorted and abstracted to such an extent that it exists solely as an intimation, a ghostly presence that haunts the almost dreamy (or nightmarish) canvas: a hazy, disquieting mix of spraypainted blues, greens, purples and pinks with shocks of orange, overlaid with graffitilike black markings that coalesce into suggestions of body parts.

That Mehretu utterly obscures the source image speaks to her consistent commitment to what Édouard Glissant terms ‘the right to opacity’: the right of diasporic subjects – both Black and queer – to refuse transparency and legibility when structures of power demand their utter knowability as the precondition of regulation, domination and control. The enduring appeal of the language of abstraction for Mehretu is precisely this refusal of intelligibility; this is at the heart of her practice, and can be seen as her repudiation of the disciplinary impulse to classification, transparency and knowability that is the legacy of colonial modernity. The queerness of both Sikander’s and Mehretu’s work, then, resides not only in the ways in which it allows us to become attuned to the intimacies of apparently discrete times and spaces. Its queerness also resides in its refusal to be known and to instead allow us to glimpse, from within the indeterminate space of the palimpsest, blur, absence, ruin and erasure, the possibility of an elsewhere and a something else.

Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, through 26 September

Julie Mehretu is at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through 8 August

From the Summer 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia