City as Studio, an exhibition currently on view at Hong Kong’s K11 Musea presents the urban landscape as a space for expression and creativity

There are many theories about what makes a city, ranging from the architectural to the psychological, from a space occupied by a collection of individuals to a collection of shared spaces, from planned development to endless sprawl. City as Studio, an exhibition currently on view at K11 Musea in Hong Kong adds to this discourse by presenting the urban landscape as a space for expression and creativity. As a space in which everyone, potentially, can leave their mark. Curated by US art dealer Jeffrey Deitch – who, through his gallery Deitch Projects and a number of related exhibitions, did more than most to make street art accepted in the museum context – and staged in the context of an urban shopping mall, the exhibition traces the development of graffiti in the US, from its origins during the 1970s through to the artform’s international spread and changing status in the present day. Presented in an exhibition space, it also allows for a deeper look at how its forms and materials both diverge from and converge with more mainstream trends in the development of contemporary art, which ultimately (as the fact of this exhibition demonstrates) absorbed it as one of its more popular (and, dare we say it, potentially democratic) modes of expression. As well as its connections with fashion, design (both clearly visible in the shops adjoining the Musea), various urban subcultures (skate-culture featuring prominently), social and political causes.

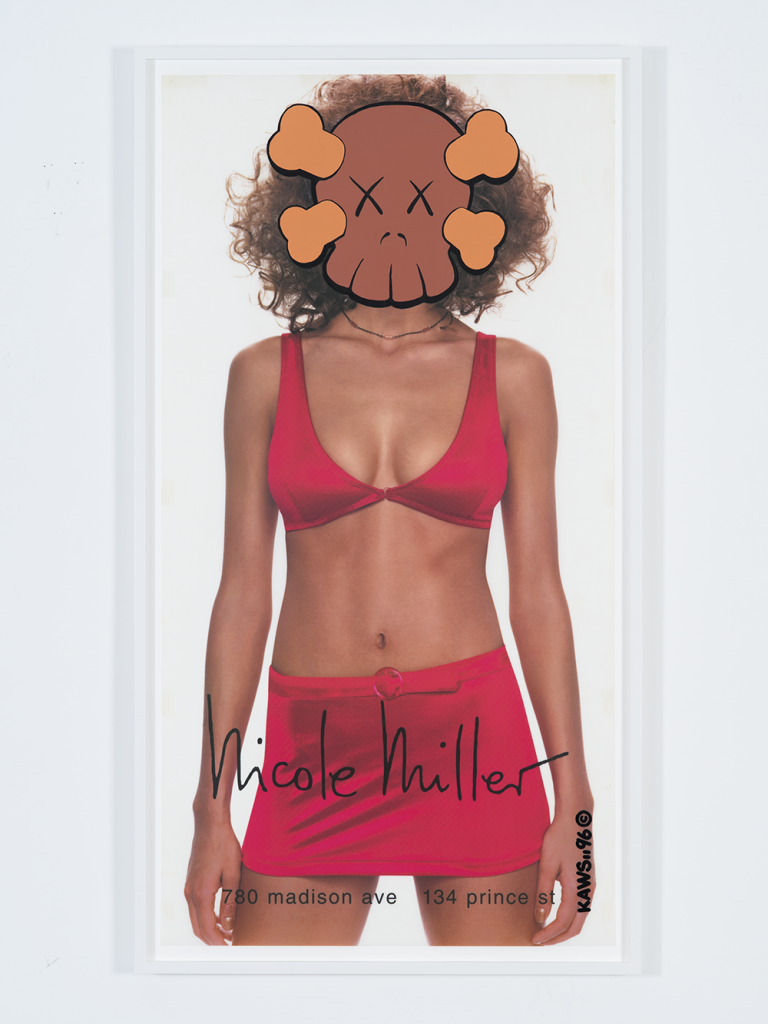

Along the way we encounter pioneering figures, such as Futura and Fab 5 Freddy, as well as some of the best-known artists of the late twentieth century, such as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose artwork continues to inspire everything from carpet design to trainers while continuing to set records at international art auctions; some of the most popular artists of our own times such as KAWS, Banksy affiliate AIKO (though the exhibition demonstrates why she doesn’t need mention of the Banksy connection to confirm her importance), and, of course, the currently ubiquitous Martin Wong. Before going all the way through to Hong Kong-based artists such as Uncle, who work in a space that negotiates Chinese characters and Western-influenced artforms. Proof, if any were needed, of how graffiti has become an international culture as much as it was once the product of the need for local expression.

New York

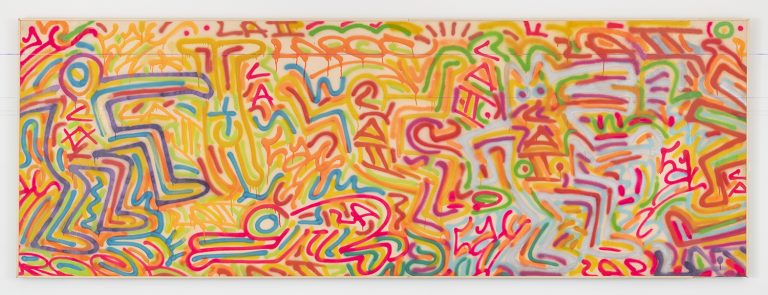

From Lee Quiñones and Rammellzee’s 1970s subway train murals to the 1980 Times Square Show that exhibited the works of new wave graffiti artists, street art in New York crawled out of its underground corners and drifted through popular culture via film and music, as the city itself went through mass gentrification. The first section in the show features the names such as FUTURA, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Lady Pink whose ubiquitous presence in contemporary visual culture testify to a continuing stardom.

4 images

Installation views, City as Studio. Courtesy K11 Musea; Jean-Michel Basquiat, Valentine, 1984. Acrylic on canvas, 183 x 142 cm. © Lisa Kato. Courtesy Paige Powell; Keith Haring / LA II, Untitled, 1983, spray paint in wood, 115 x 315 cm. Photo: Adam Reich. © LA II / Keith Haring Foundation. Courtesy K11 Collection

Los Angeles

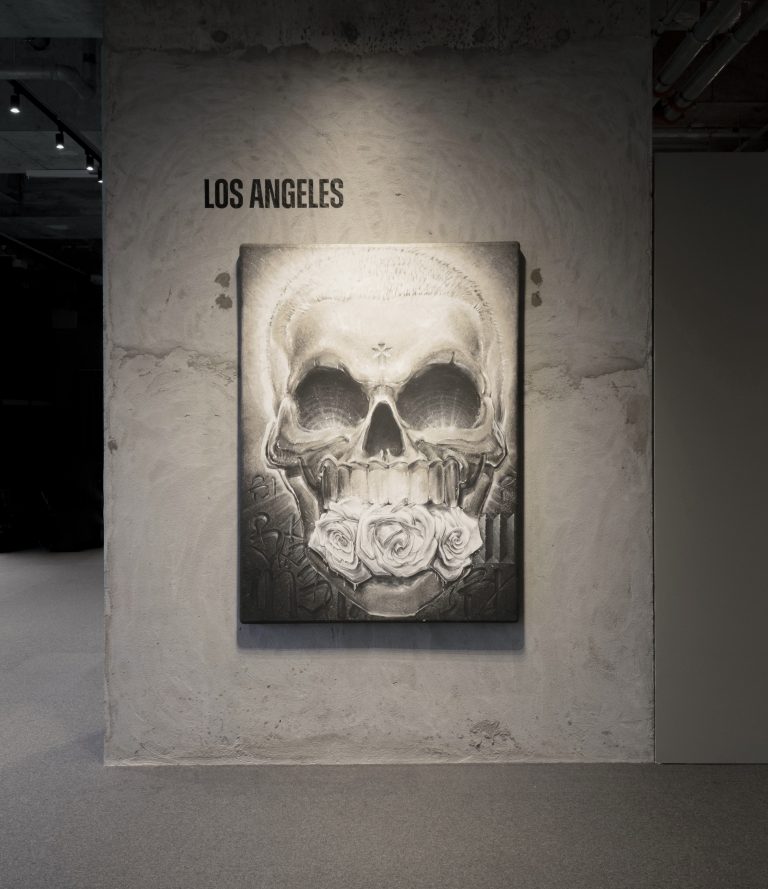

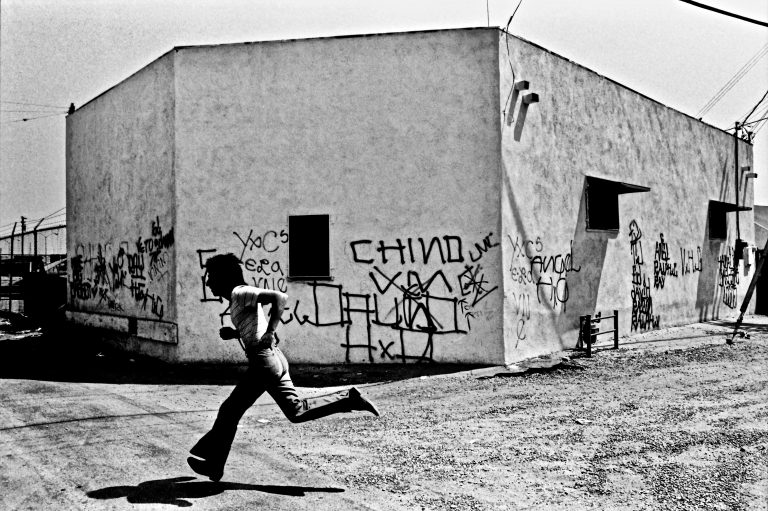

Rooted in local Cholo graffiti, a graphic style used by chicano gangs to mark their turf, artists in Los Angeles have worked with this visual form which combines gothic newspaper fonts and Mayan characters. Unlike New York Wild Style graffiti drawings that quickly gained in popularity across the US, the Cholo graffiti style was largely confined to the east LA and Venice regions. This section highlights Chaz Bojórquez, Henry Chalfant, Gusmano Cesaretti and Mister Cartoon, as well as contemporary filmmakers’ efforts to document the cholo subculture.

4 images

Installation views, City as Studio. Courtesy K11 Musea; Chaz Bojórquez, Mr. Lucky, 2019/1969. Acrylic paint, stencil with spraycan on canvas. 203 x 183 cm. Collection of Dave Tourjé. Courtesy the Artist; Gusmano Cesaretti, Chaz Running, 1973. Photo © Gusmano Cesaretti. Courtesy the artist

San Francisco

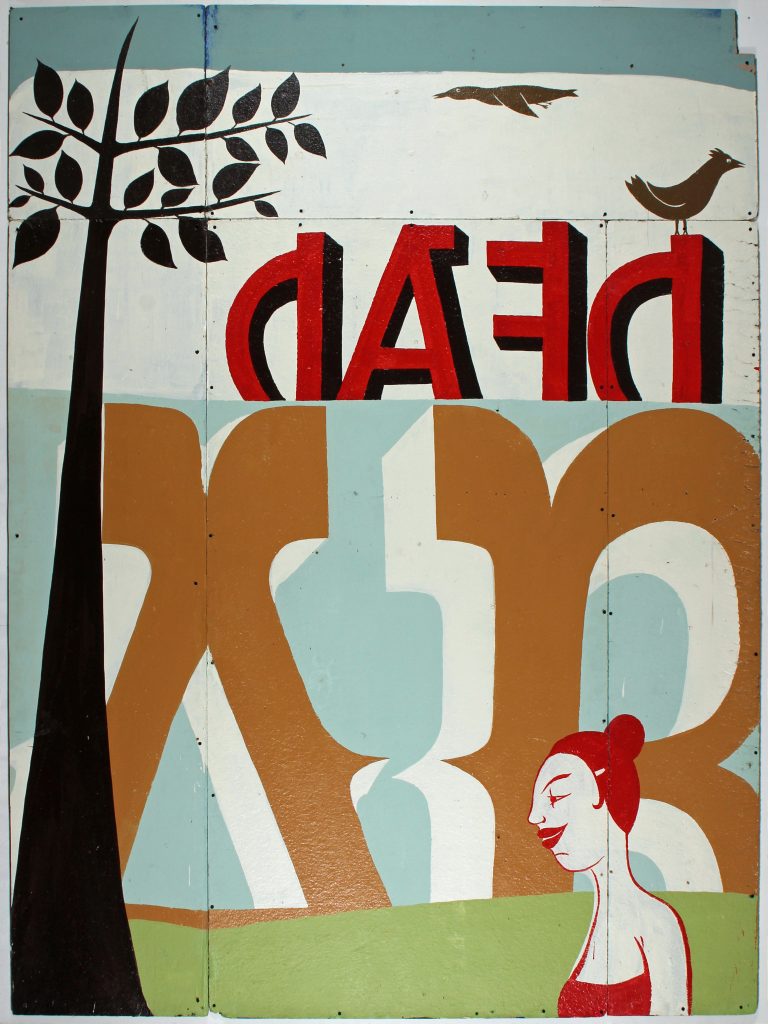

Street art in San Francisco underwent significant creative and stylistic development from the 1990s onwards, a transformation that saw graffiti, which was previously limited to tagging, used as a medium for larger pictorially-inspired paintings and murals on street walls. This was largely spearheaded by the counterculture and subculture that emerged from the Mission District, including the art school student-led movement The Mission School. The School, which was aligned with the Los Angeles-founded lowbrow art movement, spanned areas including underground comics and cartoons, DIY visual arts, sign painting and skateboard culture. Presented here are works by artists including Barry McGee, Margaret Kilgallen, Ruby Neri and Craig Costello.

4 images

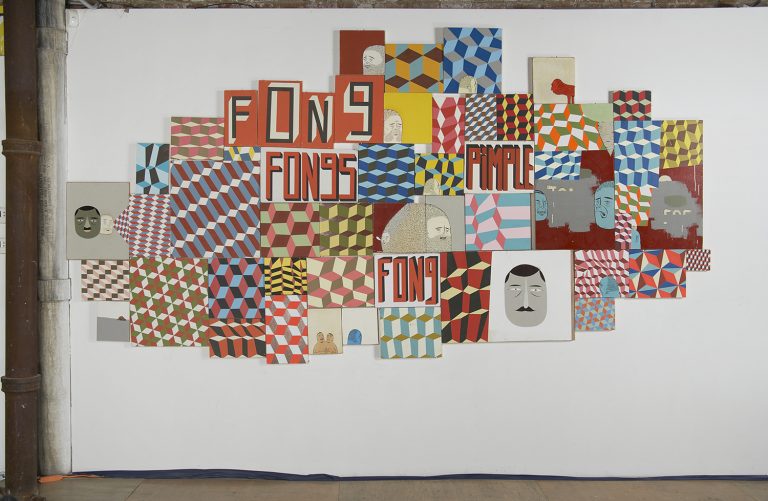

Installation view, City as Studio. Courtesy K11 Musea; Craig Costello, Untitled, 2011, latex enamel and Krink on steel mailbox, 139.7 x 73.7 x 73.7 cm / Untitled, 2011, latex enamel and Krink on steel mailbox, 127 x 63.5 x 63.5 cm. Courtesy the Artist; Margaret Kilgallen, Untitled, 1999, latex on panel, 315 x 236 cm. Collection of Michael and Teresa Fazio. Photo © Tiana Fazio. Courtesy Mike Fazio; Barry McGee: One More Thing, installation view at Deitch Projects, New York, 2005. Courtesy the artist and Jeffrey Deitch

New Generation Artists

From the mid-1980s to the 1990s in New York, innovation in graffiti was born out of necessity following a period of stagnation caused by government restrictions imposed on public platforms (campaigns included the Clean Train Movement, which saw graffiti scrubbed from subway cars and the introduction of graffiti-repellent coating on new trains) and increased rent that caused the closure of galleries. Artists turned their attention towards creative street interventions, sculpture, and political and community work. Appealing to mass audiences allowed street art to gain a foothold in the fashion world and product design, which saw artists collaborating with brands to bring graffiti to a wider market. While street art was undergoing a mainstream renaissance in the US, graffiti was also being cultivated as a distinct artform across the rest of the globe. Included here are works by KAWS, Swoon, Shepard Fairey, AIKO, André Saraiva, Todd James, Stephen Powers, OSGEMEOS, and Haroshi.

5 images

Installation view, City as Studio. Courtesy K11 Musea; AIKO, Kiss, 2017. 117 x 86 cm, mixed media on canvas. Courtesy the artist; André Saraiva, Mailbox, 2019, approx. 48 x 25 x 55 cm, enamel on metal. Courtesy the artist; Haroshi, Mosh Pit, 2019, skateboard decks, 500 x 500 x 2 cm. Photo © Genevieve Hanson. Courtesy the artist, Jeffrey Deitch, and NANZUKA; KAWS, Untitled (Nicole Miller), 1996, acrylic on existing advertising poster, 128 x 66 inches. Courtesy the artist

City as Studio at K11 Musea, Hong Kong, through 14 May