It’s perhaps fitting that figurative painting – historical bastion of the male artist – should be so confidently ransacked and remade by an artist who had to put up for so long with an artworld that kept women at the margins

There’s a small painting, the oldest one, in the opening room of this chronologically organised retrospective, that seems to anticipate something of the coldly quizzical, dreamlike register of sexual anxiety and violence found in Paula Rego’s later work; the work for which, in the last 30 years, Rego has become famous. The Interrogation (1950) would have been painted when she was fifteen, two years before she enrolled at London’s Slade School, having been sent to Britain by parents keen to get her away from the catholic conservatism and political repression of Portugal’s one-party dictatorship under António de Oliveira Salazar. In the painting, a skinny, drably clothed woman sits on a chair, head bowed and clasped in one hand, as two male figures, their heads outside of the frame, stand threateningly on either side of her, fists clenched.

The odd feature – maybe unintended by the young painter but diverting the viewer’s attention within this otherwise formulaic attempt at political realism – is the slight bulge in the crotch of the man on the right. Once seen, it’s hard to unsee, but it lets slip something about what Rego would come to be known for, years later: a sardonic, inquiring, discomfiting attention to the power of men and the rebellion of women, and of desire and violence; a political question embedded in how women might be depicted, but also – critical for any consideration of Rego’s work – how women depict themselves.

The Interrogation sits awkwardly outside and before Rego’s career as a woman painter in a world of men: marrying her tutor Victor Willing, living between Britain and Portugal, and by the beginning of the 1960s rejecting the realist mannerism of the Slade in favour of a wild, crude, Dubuffet-inspired mix of painting and collage, full of surrealistic biomorphic forms and bitter satire of the authoritarian conditions in her native Portugal. Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960) is a gathering of abject figures: some kind of white bottom on legs, puking out of a long neck, next to what looks like a pear (or vulva?) atop a hairy fruit or testicle.

It’s hard not to get the sense here that, through the 1960s, Rego is struggling to work out whether the avant-garde legacies of art brut, surrealism and expressionism could really work for her, as the styles of the prewar are tried on like costumes, while other more recent trends in the art of the time jostle for her interest. Turkish Bath (1960) incorporates bits of consumer advertising for women’s cosmetics (one fragment is apparently for some bogus ointment for breast enlargement), nodding to the advent of Pop art, along with the clean, flat colours allowed by the arrival of acrylic paint, but also groping to work out how to address the new consumer culture’s objectification of women from a woman’s perspective. By the mid-60s Rego’s canvases are full of twisted, gnarled half-figures, increasingly delineated by clear graphic lines rather than sploshed paint. These are not realistic subjects, though the way they are rendered is pulling them back to a sense of realistic forms and bodies; the most recent of these, The Firemen of Alijo (1966), is a baroque tumble of mythical figures falling out of a terracotta sky, a fusion of cartooning, fishtails, ferns and fins, bits of architecture, intestine-like trails and much else that evades description.

And then, it seems, Rego has had enough of this Pop-retrofitted surrealism. The Firemen, if we follow the biographical story, was followed by the death of her father, depression and what the artist has described as ‘general decline for years’. Jungian therapy would bring her back to folk tales and fairy stories, and a return to more traditional means of drawing and depiction.

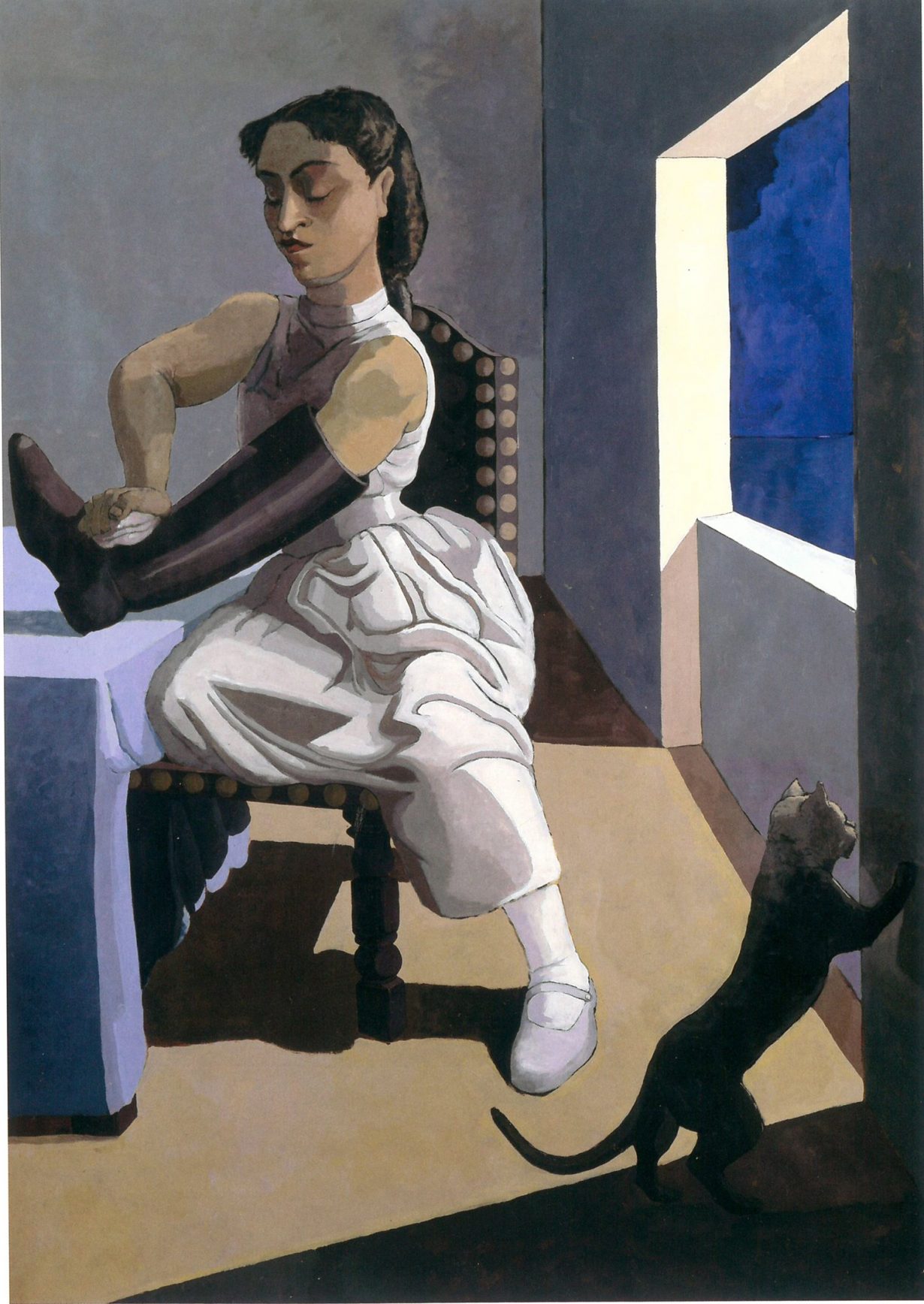

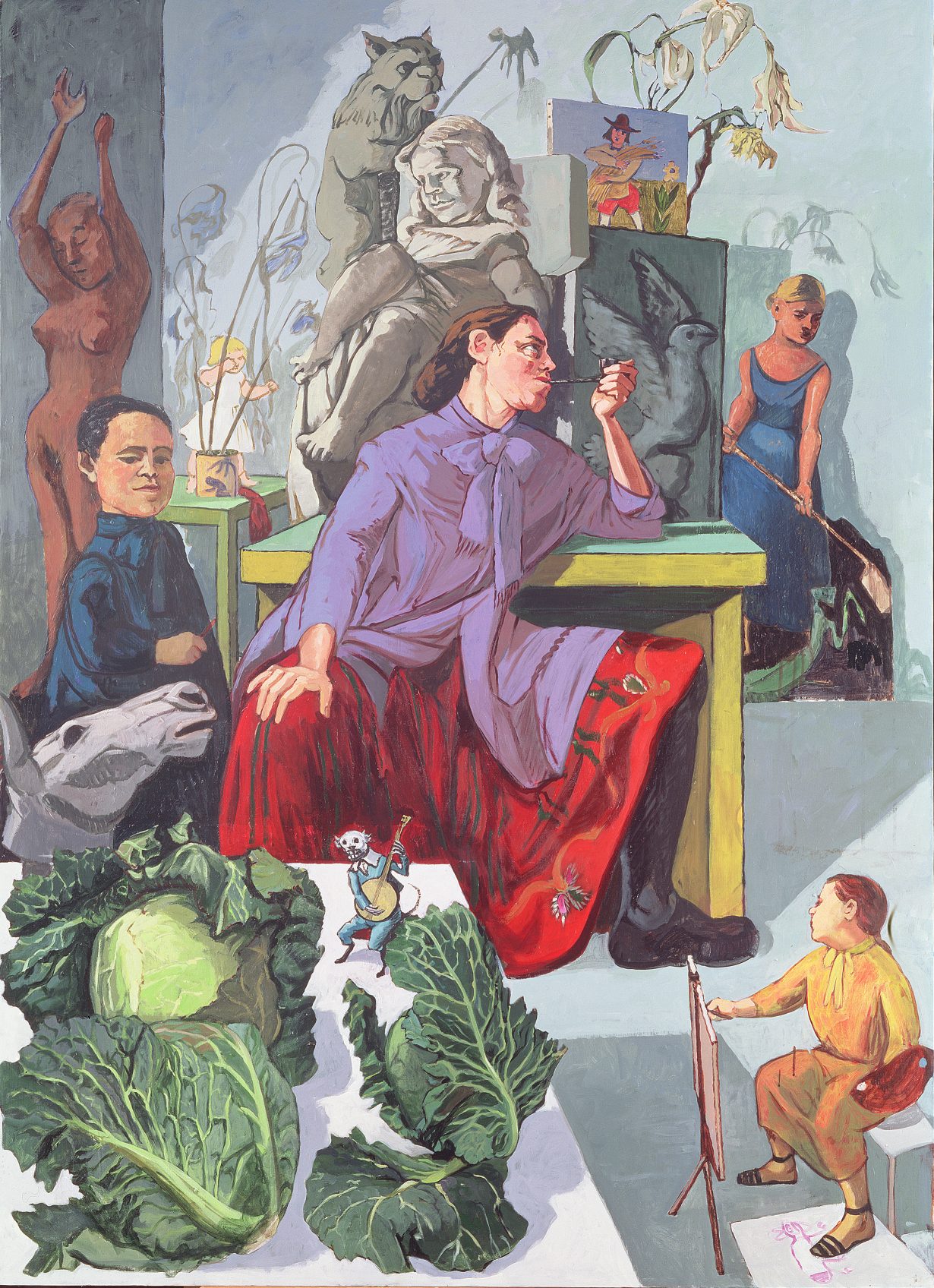

Rego’s way through to her knowing, claustrophobic world – of determined young women and childlike adults in De Chirico-esque interiors, where intimacy is forever troubled by sadism and obsession – was through the return to figuration that more broadly marked the end of the 70s and early 80s. Paintings like the creepy The Little Murderess, tiptoeing to strangle her victim, or The Policeman’s Daughter (both 1987), her arm dutifully thrust into a riding boot as she polishes it by moonlight, opened this otherwise rather blokeish reaction to the possibilities of psychosexual mischief and a female view of gendered power and codependency, just as the artworld was trying to work out the contradictions of the ‘revival of painting’, while also trying to make sense of feminist theory. By the 1990s Rego is in full stride. Dog Woman (1994) is still ugly and impressive, her baying, cornered model devoid of dignity, left with only a savage will to survive and stand her ground. A more subdued brutality suffuses the series of large Untitled pastels Rego made in response to the failed referendum on legalising abortion in Portugal in 1998. Rego’s weary, impassive women lie and kneel alongside plastic buckets and squat on bedpans that, it’s implied, are the miserable accessories of criminalised abortion.

By the 2000s Rego’s scope combines sexual politics, patriarchy and the spectres of fascism and Portugal’s own history of colonialism in ever more ambitious allegorical scenes in which her female subjects appear alongside nightmarishly outsize puppetlike characters, such as in the triptych The Pillowman (2004), with its oppressively flaccid, bulbous-headed figure, always asleep while women look after him, with glances that blend anxiety and disdain. Hints of a broader violence and repression – Christian crucifixes, the peculiarly tropical coastal background of the middle painting (and Pillowman’s own racially caricatured head) – turn the psychopolitical tensions of race, sex and class into a sinister, overlit burlesque.

It’s maybe fitting that figurative painting – historical bastion of the male artist and (in today’s language) the ‘male gaze’ – should be so confidently ransacked and remade by an artist who had to put up for so long with an artworld that kept women at the margins. But Rego’s skill at materialising her subtle, self-conscious view of empathy, desire and the powerful forces that corrupt the lives of women and men, invents a world that, while acknowledging this everyday damage, does so knowing it can be overcome.

Paula Rego, Tate Britain, London, 7 July – 24 October