Is there a future for the contemporary art biennial? The format of the ‘large international exhibition’ – the big, globally ubiquitous curated exhibition – may be starting to show signs of fatigue. Last week Manifesta, the itinerant European biennial whose 12th edition in 2018 will be staged in Sicily’s capital city of Palermo, unveiled its ‘Palermo Atlas’ – an ‘urban study’ of the city, commissioned by the biennial from architect Rem Koolhaas’s celebrated OMA agency, as a sort of roadmap for its 2018 edition. In its press blurb, Manifesta declares that the study’s purpose is to transform ‘a nomadic art biennial into a sustainable platform for social change’, through which it ‘hopes to extend its impact beyond just engaging audiences with contemporary art… towards providing Palermo citizens with tools to imagine the future of their city.’ Implied in these aspirations is that the biennial format is currently the opposite – that the biennial is neither an agent for social change nor has it much of an impact beyond the narrow audience for contemporary art.

Perhaps Manifesta’s renewed preoccupation with its social impact and legacy, and its rationale for its ‘Palermo Atlas’, is a reaction to its increasingly troubled identity. A product of post-Cold War European optimism, Manifesta has tended to gravitate to those locations which represented the ‘front lines’ of the new Europe, although those interventions have been regularly controversial; the 2006 edition in Nicosia, on the divided island of Cyprus, was cancelled, mired in local political wrangling. The 2014 St Petersburg edition was caught up in bitter accusations of complicity with an increasingly repressive Putin administration; while last year’s edition, in the Swiss financier city of Zurich was met with a lukewarm critical response.

it points to a broader anxiety about the legitimacy of large international exhibitions – especially when these declare themselves interested in issues of social participation and political engagement

But in broader sense, it also points to a broader anxiety about the continued legitimacy of large international exhibitions – especially when such exhibitions now regularly declare themselves to be interested in issues of social participation and political engagement. This year’s edition of the quinquennial Documenta, curated by Adam Szymczyk, strained to combine the exhibition of artworks with a more involved form of art-as-activism, with its emphasis on the politics of migration, climate change and the experience of minorities. Documenta’s uncomfortable engagement with the austerity-hit capital city of Athens (for its initial instalment, before it returned to provincial Kassel) suggested a self-consciousness awareness of the limitations of the biennial format in relation to the contexts and tensions of its host city. Manifesta’s gambit is rather more explicitly constructive, proposing to overhaul the format of the biennial exhibition entirely, with an ‘interdisciplinary approach’ led by a firm of architects.

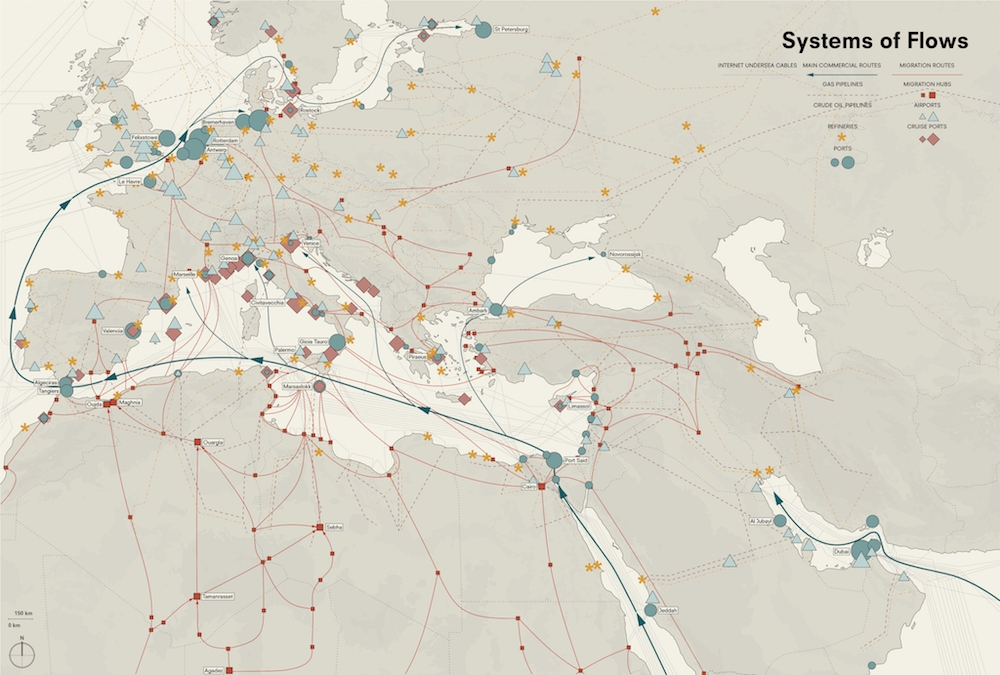

Thematically, however, Manifesta 12 is just as obsessed with the kinds of issues that exercise Documenta and the zeitgeist of crisis-fixated pessimism you find among today’s international network of itinerant curators – almost inevitably, in picking on Palermo, Manifesta wants it to be all about ‘migration and climate change’. OMA’s scary-looking flow-diagrams show the movement of people, climate and species encroaching on Europe from north Africa and the Middle East.

Themes of global crisis have come to dominate contemporary art culture, and the power they exert in the public imagination magnifies the sense of failure and redundancy among the layers of art-managing curators. After all, it must be hard not to feel some sort of shame and frustration at the spectacle of your large international exhibition parachuting into venues that have their own social and political problems; there’s a Marie-Antoinette-ish quality to it, however radical and engaged artists and curators try to see themselves.

But ironically, just as that sense of impotence grows, it provokes big, politically-minded shows like Manifesta to intensify their attempts to be socially engaged, to ‘make a difference’. Hence the choice of Palermo, the extraordinary, dilapidated, ancient city, a hub of Mediterranean antiquity. So according to Manifesta director Hedwig Fijen, ‘Manifesta 12 in Palermo … will be a fantastic opportunity for the city to reinvigorate its local and international identity’. Manifesta will ‘investigate how great the role of cultural intervention can be in allowing the Palermitani citizens to take back ownership of their city.’

while art’s effect as a form of socio-political intervention always seems to fall short, biennial curators redouble their efforts to make the format more pro-active

There is something condescending about this kind of rhetoric – as if the people of Palermo aren’t capable of effecting social change for themselves, or of figuring out what they want for their city by their own efforts. So while it’s perhaps too soon to judge, it’s notable that the of team of four interdisciplinary ‘creative mediators’ leading Manifesta 12 – OMA’s Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, Dutch filmmaker Bregtje van der Haak, Spanish architect Andrés Jaque and Swiss curator Mirjam Varadinis – have little to do with Sicily. Only Laparelli was born there, but he’s been with OMA in Rotterdam since 2007. Similarly, while Documenta billed itself as ‘learning from Athens’, the positions it took on a range of issues were essentially those which the curator and his associates wanted it to take. Yet while art’s effect as a form of socio-political intervention always seems to fall short, biennial curators redouble their efforts to make the format itself more pro-active, more interventionist – hence the drift towards the total management of the biennial format in Documenta and Manifesta.

There’s a paradox to the evolution of the large international exhibition – even though the format may hit moments of crisis and self-doubt, the format itself doesn’t go away. Regardless of the content, the large international exhibition format is still in demand by the cities eager to attract cultural tourism and international attention. So, on another Mediterranean island, this year’s Venice Biennale – ‘Viva, Arte Viva!’ – curated by Christine Macel, could swim in its own high-minded hyperbole about how, ‘in a world full of conflicts and shocks, art bears witness to the most precious part of what makes us human’. That may be so, but the 2017 edition is also the longest-opening of any edition of the Biennale in living memory. If the 1968 edition ran for just under four months, today’s Biennale occupies six and a half months of the tourist calendar, from mid-May to the end of November. In post-crash Europe, the value of a major cultural event continues to be irresistible to local and national politicians.

The 1968 Biennale, opening just after the student uprisings of May that year, was famously dubbed the ‘Biennale of the police’, as artists boycotted the Biennale in response to the authorities’ heavy-handed response to art students’ protests in the days leading up to the opening. In an issue of ArtReview’s predecessor Arts Review, the critic and historian J.P. Hodin fumed at all those ‘artists who cannot shed the ‘Cubist’, ‘Dadaist’ prejudice of first destroying what was there, without being able to put something in its place.’ As far as the traditionalist Hodin was concerned, protestors may have legitimate criticisms of the big show, but the show still had to go on. The option of not having something to put its place was unthinkable.

That, of course, is the dilemma for the biennial format today – that while it remains a reputation-engine for art’s economy the radical aspirations of curators push the big international exhibition to activate, facilitate and empower its host community, to be more political. But those aspirations are a delusion, since while curators can delegate their authority to various ‘creative mediators’, the large international exhibition is inevitably a top-down structure which, by definition, cannot be reformed. That’s not to say that the biennial can never be a format by which the best art from everywhere can be seen by the most people. But it does mean that what that art is, and who chooses, can’t be left to the judgement of one individual. Ironically, it was after the crisis of the 1968 biennial that the role of the ubercurator took shape. Half a century on, it’s time to rethink that structure. The show doesn’t have to go on.

Published online July 17 2017