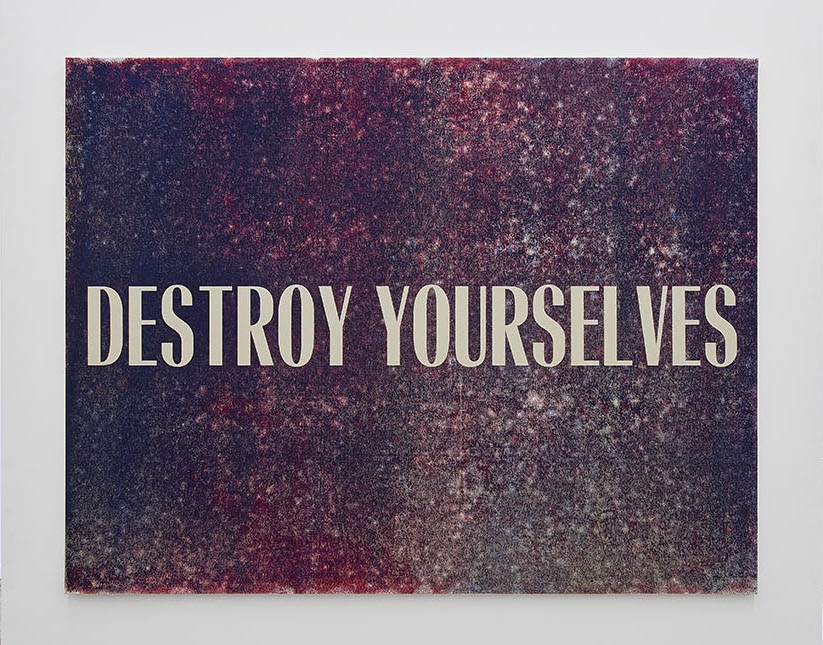

One of my oldest friends happened to be in Chicago while I was there last week for EXPO Chicago. I had figured this out while idly scrolling through Instagram stories, and so I messaged her. The following night we were eating deep-dish pizza and chicken wings together, and I even met her mom. (Thanks for that dinner, you two.) I was also lucky to see my friends Raven and Jesse, the latter of whom I once described in this magazine as possessing the ‘gravitas of a goofy rabbi’. It was the first time I had seen Jesse since my last visit to Chicago, and he quipped that I had outed him in my report from that time. “It’s 2018, Sam,” he joked. “Trump doesn’t need to know I’m a Jew.” Mike and Natalie, who run the gallery Regards, both gave me a hug when I stopped by their Chicago premises – these are two people who really take you into their arms. The gallery was showing a two-person exhibition called Violence, which featured Israel Lund and Keren Cytter. ‘Destroy yourselves’, reads a message on a largescale painting by Lund; Cytter’s film follows a young man as he, well, destroyed himself – and others along the way. Mike and Natalie took me out for frozen negronis and Amish chicken, and introduced me to another artist on their roster, Devon. He and I talked about how much we each love Milan – just completely love it. The backstory to all this is that Christine Blasey Ford was testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee about being sexually assaulted by Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. The hearing took place the same day EXPO Chicago opened, with the final vote on Kavanaugh’s potential confirmation expected to take place the next day (thankfully, it was postponed). I went looking for friends because it was hard to care about an art fair in these circumstances.

I’ve attended several editions of EXPO, and the optimism has finally worn off. Galleries from New York or Los Angeles, Oslo or Paris, once believed the fair would offer them entree to Chicago markets, or that they could use attendance as an opportunity to hand-deliver artworks to established clients. But this year’s edition lacked a great deal of galleries who participate regularly in the Friezes and Art Basels; the running up of large tabs while attending the many fairs populating the art calendar would seem to be forcing galleries to further limit their appearances, and this was in evidence in Chicago. Many young galleries who once made the trek to the Windy City in hopes of opening new frontiers had got wise to what the fair had to offer. I don’t make these observations as conjecture but from speaking with former participants, though a quick tour of the fair supports my theory of a narrowing of offerings. That said, I spent a lot of time in EXPO VIDEO, a special theatre set up near the entrance. EXPO invited Anna Gritz from the KW Institute in Berlin to select the programme, and it provided welcome criticism of art’s privileged status. Scrolling text in Tony Cokes’s video offers a literal and quite cogent critique of self-replicating pop culture: ‘You can project yourself on a blank wall just as easily as the highly constructed mirror of personalities, advertising, etc’, it instructs viewers. Kandis Williams’s two-channel video Eurydice (2018) revolves around a black performer’s beautiful rooftop dance performance. Exhausted by the end of his trip through the mythopoetic underworld (read: the audience’s gaze), the performer gets in his parked car and leaves.

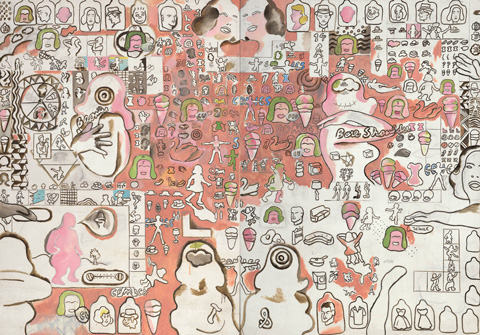

Chicago just didn’t possess the same enthusiasm I would have expected during fair time, but another critic from New York was visiting, too, and I was happy to pal around with her on our museum rounds. It took the edge off my reaction to I Was Raised on the Internet, presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art. The show merits an Urban Dictionary entry for ‘millennial’, and that’s about it, offering another survey of artists who were influenced by the Internet from an early age: a claim as general as ‘the Internet changed the world’ needs to be backed up with a point of view, not the same tired buzzwords. Honestly, though, I was more flabbergasted by Heaven and Earth: Alexander Calder and Jeff Koons, also at the MCA. It was installed in a small gallery and brings together iconic artworks from each artist in what comes across as a perverse comparison between their shared interest in childlike expression – some creepy imagination was required to bring these worlds together. Fortunately, over at the Art Institute of Chicago, the retrospective Hairy Who? 1966–1969 looked at the pivotal Chicago-based group with a novel approach. The museum has recreated several pivotal exhibitions from the eponymous collective’s shortlived existence. More exhibitions should attempt to structure themselves this way; knowing how these works were originally presented better emphasises Hairy Who’s rebellious spirit. Their collective, DIY way of working, and their eclectic and perverse sense of humour really come across here. These artists would eventually be termed The Imagists, and appreciated as local dogma. But their legacy lives on in every artist-run gallery with a kooky name such as Soccer Club Club, Prairie and all the others Chicago has become known for.

My fellow New Yorker and I also visited 360 Chicago, an observation deck at the top of the John Hancock Building. We watched the sun set over the western neighbourhoods and counted the number of swimming pools we could see on the top of apartment buildings. Cars crawled along the shore of Lake Michigan to the Northern Suburbs. The region looks entirely flat from 300 metres up, but unlike a popular stereotype applied to cities in the nation’s middle, it’s also possible to see the dozens of airplanes buzzing around Chicago’s airspace, awaiting their landing slots at one of its international airports. Indeed, there’s good reason that pioneering filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek’s films came to land here, too. His POEMFIELD no. 7 (1967–68) plays on an endless loop at DOCUMENT, a gallery whose astute programme is often greater than the sum of its parts. Shown in the original 16mm, the film flickers through VanDerBeek’s early experiments in digital animation. The actual poem that emerges is a lot about peace; only a few minutes long, it’s easy to enjoy the film several times while lounging in one of the beanbag chairs the gallery has supplied. I was somewhat distressed to learn that DOCUMENT’s install did not follow VanDerBeek’s frequent intention to screen the film with others from the POEMFIELD series, as part of an immersive cinematic environment. But my feelings quickly subsided, the advantages of a one-on-one experience having been made clear to me throughout the weekend. Rather than worry about what ought to be, I focused on the poem’s last three frames instead. They read ‘No’, ‘More’ and ‘War’, respectively. In Chicago, that’s how I found peace.

Published online 3 October 2018