Can you teach an old dog new tricks? And can cutting edge technology do the teaching? Christie’s seems to think so. Their Art + Tech Summit: Exploring Blockchain, co-organised with Vastari (a platform offering data-driven solutions for museums to promote and organise exhibitions), was representative of the old auction house’s enthusiasm for the promise of blockchain technology, which the summit’s organisers were keen to present as a potentially revolutionary solution to the global art industry’s traditional aversion to making its markets transparent, trustworthy and accountable.

So a packed audience of over 200 well-heeled gallerists, tech entrepreneurs and perhaps not a few discreet collectors faced a packed agenda of keynotes and panel discussions dealing with how blockchain technology might transform the making of artworks, how it could transform the laborious and risky business of authentication and provenance, and how cryptocurrency models might make the art market more ‘liquid’, allowing small investors to enter what has been a traditionally exclusive market.

It was a learning-curve day for many. Blockchain technology, popularised by the rise of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, is evangelised by many tech enthusiasts as the Next Big Thing for the digital economy. At its core are two basic concepts: distributed, decentralised peer-to-peer computing with no central authority; and the promise an unalterable, mutually guaranteed and transparent record of past events and transactions. For Net utopians it’s a way to free us from centralised power and authority of governments and big business. To sceptics it’s another digital fad, the next bottle of Web snake oil. What, if any, of it actually works right now is another matter.

It’s that increasing distance and anonymity which is driving the demand for new, networked forms of trust and verifiability

So Blockchain.com’s Nicolas Cary could enthuse that the blockchain had the potential to ‘give every single thing on the planet a digital identity, and then trade it’ – allowing poorer populations to access international payment systems, while store value would act as a hedge against their own more unstable and weak currencies. Others were more sanguine about the disruptive potential of blockchain computing. Anton Ruddenklau, of KPMG (the giant accountancy and management consultancy), warned during the first panel discussion that blockchain applications were barely only beginning to prove themselves, noting that most of the projects he was dealing with were in the more provable sector of logistics supply-chain systems. Ruddenklau seemed to enjoy being the party-pooper; discussing KPMG’s other line of blockchain work, with central banks, he suggested that if central bank currencies (or ‘fiat’ currencies) were developed into blockchain currencies themselves, ‘Bitcoin would be out of the picture’. Countering the likes of Ruddenklau were tech entrepreneurs like Richard Muirhead and Vanessa Grellet. For Fabric Venture’s Muirhead, the promise that networks held for collaboration between people was compelling and inevitable, though there wouldn’t be a risk-free route to this; Grellet, of ConsenSys, could see new ways of sharing data that didn’t compromise privacy and security, allowing businesses and individuals who would normally keep information from each other to benefit from selectively sharing information in mutually beneficial ways.

What became evident through the course of the day is that big corporations like KPMG, who have a lot of their reputation and business tied up with governments, centralised law-making and regulation, are the most nervous about blockchain. Lawyer Jonathan Kewley (from mega-law-firm Clifford Chance) offered a scare-list of problems – data privacy regulation is impossible if a blockchain database exists across computers in 50 different countries; cybersecurity is a myth; and for all the talk of ‘democratisation’, most cloud-computing platforms are still controlled by the giant US tech platforms like Amazon and Microsoft, regardless of whether they might run blockchain applications.

After the naysayers, Christie’s photography specialist Anne Bracegirdle made the case for the adoption of blockchain by the art market, insisting that it would simplify transactions and enhance transparency, trust and security. But Bracegirdle’s main push was for the use of blockchain for artists to monetise their work – enabling limited editions of images that might be sold and resold, with the blockchain acting as both the source of the image and its verification.

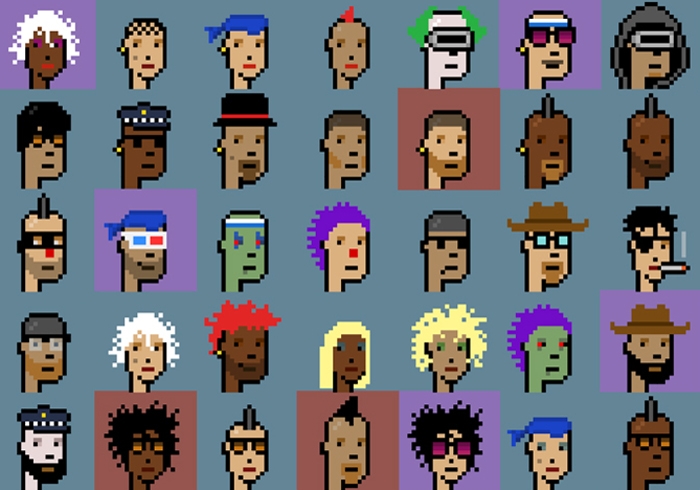

As it turned out, controlling and monetising distribution of creative assets was the main issue for the panel of artist-developers – all US based – that followed. Matt Hall’s CryptoPunks project generates and circulates 10,000 8-bit cartoon characters through the Ethereum blockchain. Yehudit Mam’s DADA.nyc sells ranges of artists’ original digital imagery, setting up a profit share where the artist also gets a cut of later resales of their editions. John Zettler’s R.A.R.E. Network does a similar job for artists’ digital images, photography and animations. What was at stake was the possibility of fusing control of production, distribution and monetisation for the ‘little guy’ artist, so that creatives might produce digital work and not get ripped off. For Mam, the goal was to bring the experience of collecting to a bigger public.

It was notable that in the discussion around producing ‘scarce’ artworks, these innovators were keen to adopt the traditional art market’s model of limited supply of objects, rather than the mass market licensing-or-subscription model for cultural works – the limited-edition Jeff Koons sculpture, not the Shrek DVD on your shelf or your Netflix subscription. That tension – between the unlimited reproducibility of digital entities and the potentially very limited nature of physical artworks ran through the rest of the day’s discussion – this was really about the art market, after all.

Because unlimited reproducibility is, it turns out, the problem for physical art objects too, though in a slightly different way to virtual digital objects. Verifying that an artwork really is what it’s supposed to be is a massive, costly headache, in a market that privileges both the exclusivity of the object and anonymity in buying it. So Nanne Dekking, onetime high-up at Sotheby’s but now running Artory, a digital registry of verified information about artworks, could point out that the biggest impediment to the secondary market was mistrust; Jess Houlgrave, of startup Codex Protocol observed that many buyers operated behind layers of intermediary and offshore entities. It wasn’t surprising that Dekking and Houlgrave shared their panel with online auctioneer Paddle 8’s Ram Nadella – web innovators have already changed the way collectors connect with galleries and artworks, making the art market more ‘virtual’ and anonymous than ever before. Gone are the days of the collector walking into a gallery to meet a dealer to look at a work. And it’s that increasing distance and anonymity in art market transactions which is driving the demand – fully evident at Exploring Blockchain – for new, networked forms of trust and verifiability.

Why are people – rich and not so rich – so keen to park their wealth in what are, essentially, unproductive assets?

But equally obvious in the push for a more trustworthy art market is the keen desire to make lots of money out of it. Inevitably, cryptocurrency approaches to financialising the art market loomed large. A final panel included representatives from Maecenas and Look Lateral, both start-ups looking to develop ‘fractional ownership’ (see Will the Blockchain make art disappear?). It’s a simple logic – rather than buying and selling big-ticket artworks for tens of millions, why not sell shares in its value to others, who then trade those fractions with each other? Big collectors get to access the ‘liquidity’ locked up in their Warhols; small investors get to play a new kind of stock market, based on the guaranteed scarcity and recognised value of significant artworks. So what if no one actually gets to see the artworks? They’re all safely locked away in swiss freeports. Win-win?

The elephant in the room, of course, was liquidity. Where is all this spare money coming from in the world economy, and why are people – rich and not so rich – so keen to park their wealth in what are, essentially, unproductive assets? (see Liquid Value) A few speakers pointed in passing to the question of ‘store of value’, but nobody wanted to spoil the party too much by asking awkward questions. This was an opportunity for tech entrepreneurs to promote their wares, after all. Not incidentally, both Maecenas and Codex Protocol are next week getting ready to test their products – Maecenas is preparing its first trial auction, of an Andy Warhol painting; Codex Protocol is making its first ‘coin offer’ – issuing its own currency through which investors can buy into a set of blockchain services like authentication and fractional investment.

As the world economy bumps along uncertainly, the art market continues to ride surprisingly high. But in a networked economy where value is increasingly virtual and artworks are traded to ‘diversify’ investments, attaching value to scarce objects – physical or digital – is an irresistible, almost magical lure. So while the sceptics may conclude that nothing about blockchain has really proved its value, it won’t stop the art market’s enthusiasts from trying. Because, if it works, there’s a lot, lot more money to be made.

Online exclusive, published on 20 July 2018