As the year comes to a close, ArtReview’s editors look back on shows that they enjoyed this year, didn’t have a chance to review, and which may, for one reason or another, have escaped your attention…

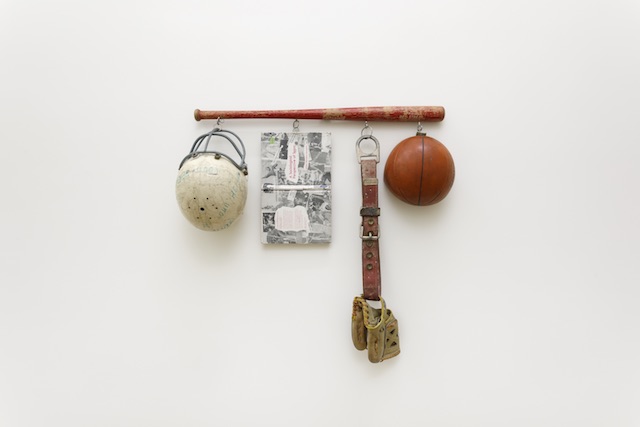

Cady Noland at MMK, Frankfurt, 27 October – 31 March 2019

If an artist refuses all exhibitions for nearly two decades, and they’re one of your favourite artists, and suddenly – out of the blue – they mount a retrospective in the country where you live, there’s a strong chance that said show will be your exhibition of the year. So it was with the Cady Noland survey at MMK Frankfurt, whose 80-odd works overflowed with the American artist’s signature x-raying of the violence beneath the skin of American culture: ominous, chrome-heavy assemblages of weaponry, gossip magazines and cameras, fearful aluminium stockades, sardonic silvery silkscreens of Patty Hearst, Lee Harvey Oswald et al. One of the artworld’s great principled recluses – no interviews, no photos – Noland appeared, with this show, to be back. True to form, though, there are no plans for it to tour.

Martin Herbert

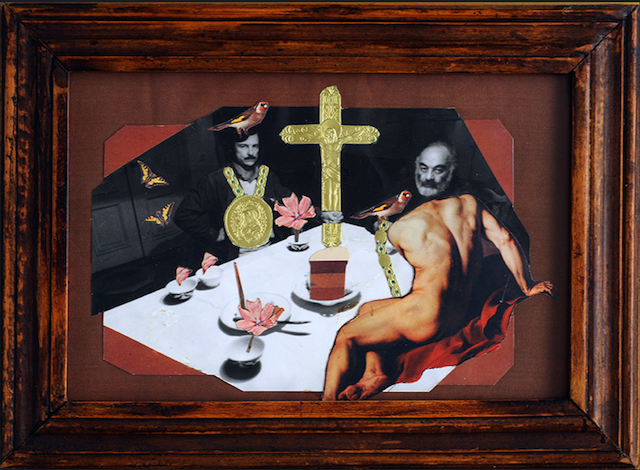

Parajanov, with Sarkis at Pera Museum, Istanbul, 13 December 2018 – 17 March 2019

The Soviet-era filmmaker Sergei Parajanov is remembered for a series of visionary films, most famously The Color of Pomegranates (1969) and its dreamlike celebration of Armenian folklore, interrupted by his conviction on politically motivated charges of homosexuality in 1974. Yet by showcasing collages, drawings, assemblages, mosaics, ceramics and textiles alongside snippets from his films and a moving homage by Sarkis, Istanbul’s Pera Museum showed how persecution, imprisonment and forced labour failed to thwart a compulsion to shape the world into meaningful forms. A childhood suitcase is reimagined as a leathery elephant head; shattered lightbulbs read like allegories in ad-hoc assemblages; tin bottle-tops scavenged in prison are embossed by hand into medallions with figures in relief. For all that it rewards political interpretation, this art is dissident not because it promotes a coherent political programme but because it resists any aesthetic (most obviously, but not exclusively, socialist realism) dictated by an ideological position which constrains the artist’s own identity, desires and cultural heritage. As such the show inspires, looking back on this year and forward to the next, a defiant hope.

Ben Eastham

Yun Hyong-keun at MMCA, Seoul, 4 August – 6 February 2019

I’m standing and staring, and staring and passing by paintings of pillars, of burned tree trunks, of gateways into a void, into a nothingness. I stop in front of Yun Hyong-keun’s Umber Blue (1977), and find I’m looking for something. But it is evasive, hovering at the periphery of what I can see, blurred, unfocused, like the thick black lines painted either side of the raw linen canvas where the edges bleed toward the middle, from ink to oil to cloth. Of the many works included in Yun’s retrospective at MMCA, Seoul, ranging from his early works in which the pigments of umber and blue can be distinguished from one another before he began to combine the two into a near black for his mid- and later works, this is the one that gets to me: to turn on the spot is to see this painting in the context of its familiars – together they form a forest, lit through with late-autumn sunlight – but staying still means to choose a gateway, a path, a direction. In a diary entry dated 1979, Yun wrote, ‘I feel that my life is like waiting for something. Waiting and waiting and waiting, but nothing ever comes.’

Fi Churchman

David Claerbout at Les Abattoirs, Toulouse, 21 September – 10 February 2019

‘Slowness’ seems to be a remedy word these days, a cure for our frantically paced capitalist and digital age. Few artists slow down time as effectively as Claerbout and his contemplative moving-image tableaux, hovering as they do between stillness and motion, flatness and depth, the real and the fabricated. Installed in the lofty nave of Toulouse’s slaughterhouse-turned-contemporary-museum, ten of works from the past decade attest to Claerbout’s technical mastery, combining analogue and digital photography together with 3D technology to bring the space and temporality of a photograph to life (you could almost feel the skin of bare-chested Elvis in his rendering of the famous 1956 portrait by Alfred Wertheimer). Elsewhere, a remake of Disney’s 1967 The Jungle Book (so well-executed it’s confusing) rescripts a jungle in which animals don’t speak, dance or raise children; instead, they behave like their own kind, hunting, sleeping, drinking from the river. Deceleration, Claerbout seems to suggest, requires a shift of perspective; one that requires us to tune back in to the rhythms of nature.

Louise Darblay

One Monument Later at National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest, 26 April – 20 September

The editor says I’m not allowed to nominate the Strava fitness app calamity as my favourite artistic moment of 2018: in January secret military bases were revealed after Strava published geotagged maps of popular running routes, which unfortunately for the US military included paths run by troops around the perimeter fences of various military installations, including camps in the Yemeni desert. The results, available to view via company’s website, were strangely moving. Featuring tight digitally rendered circles overlaid on otherwise empty terrain, the images proved an unintentional homage to mundanity, boredom and the circularity of conflict. So instead, I’ll give a shout out to the restaging, by the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest, of the three-dimensional photographic mock-ups, by Dan Er. Grigorescu, of Constantin Brâncuși’s monumental outdoor work Târgu Jiu, originally exhibited at the 1982 Venice Biennale. The deceptively simple project proved kaleidoscopic in ambition, posing questions of re-enactment, representation and the processing and reprocessing of history.

Oliver Basciano

Ellsworth Kelly: Austin at Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, permanent collection

With the year almost over, a damning question loomed over my 2018 best-of’s: who in their right mind would want to be considered the best out of a year that was just the worst? Though I struggled to reconcile art with news of yet another catastrophe, Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin, which was unveiled in February on the University of Texas, Austin campus, occasioned a moment of peace. Outside, the building resembles a stumpy Romanesque cathedral, Kelly having opted for special grey marble to project an outward serenity. Inside, however, three sets of stained glass windows, which Kelly patterned after colour spectrums, produce a stunning light show. Twelve black and white paintings (evoking the stations of the cross) also share the room, and, replacing the altar is a graceful, freestanding wooden totem. Who knew Texas is where I’d find peace.

Sam Korman

Published online, 21 December 2018