A 1997 poster by Inventory features a black-and-white wildlife photograph of a tapir, reared up on its hind legs, its forelegs spread defiantly. ‘I want more life fucker’, reads the slogan. Humour, anger and pathos, and an anti-institutional, politicised erudition are characteristics of the artist collective Inventory, which in the London art scene of the late 1990s and early 2000s was one of the more articulate and inventive agitators on the volatile border between art, culture and politics. Through exhibitions, actions and publications – notably the 14 issues of their eponymous journal, which ran from 1995 to 2005 – Inventory reworked earlier traditions of cultural dissent to rail against the banality of everyday life under capitalism, fusing the Baudelairian culture of the flaneur with the cultural analysis of Bataille and the politics of the Situationists, against the shifting context of the new cultures of anticapitalist protest and agitation of the time.

If Inventory has slipped from view in the UK since 2005, this show at Rob Tufnell offers a review of earlier work, and a sense that the group’s project might continue. Earlier works reveal a diverse range of approaches and interests, essayistic and reflective one moment, agitationist the next. Excerpts from videos of their public action Coagulum (2000), in which a group of individuals suddenly assemble into a sort of rugby scrum formation, inside a big Oxford Street retail store, remind you of the once-edgy origins of the flash mob, before it turned into an excuse for spontaneous dancing in the street and similar puke-making hipster urban sentimentalism. Borrowing its title from one of Bataille’s books, The Absence of Myth (2004), meanwhile, highlights Inventory’s knack for wresting a hidden poetics from the surface of ordinary life, as the camera cuts slowly through shots of consumer foodstuffs and household products in which the forgotten mythical names of antiquity survive – Ariel, Nike and so on.

Alongside videos and publications, the show presents objects that distil the group’s interest in redundant and destitute material forms: Three Episodes in the Relentless Process of Decay (2003) comprises three battered old fridge doors, the first bearing a rendering of motifs from ancient cave paintings (men hunting bison), a second reversed to show a panel of food icons, and a third adorned with long-faded album stickers of forgotten footballers and Baywatch stars. The Terminal Division (2002) is a grim antisquatter steel security shutter, decorated with an image of a big fish gobbling a smaller one, more resonant now than ever, during a housing crisis in which everyone is fast becoming either a landlord or a tenant.

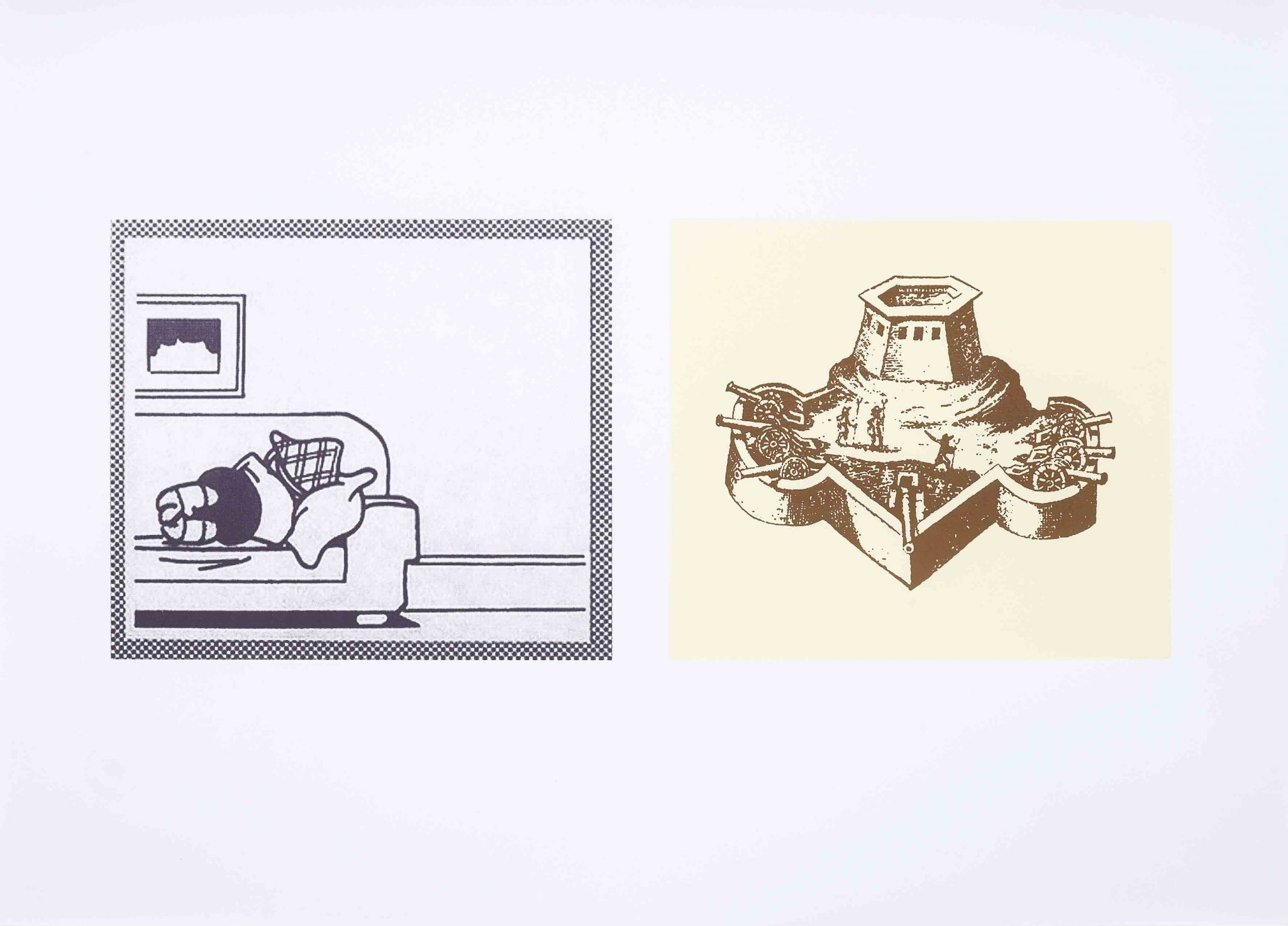

These readymades aren’t exactly subtle, but then Inventory weren’t ever pandering to the interior decoration requirements of polite collectors – Inventory’s practice has always been too wayward, too awkward to make for smoothly art-institutional professionalism. A new series of works form a sort of narrative for the group’s current predicament; Inner Emigration (2014) juxtaposes the indolent British cartoon character Andy Capp alongside an odd composite of Elizabethan travellers wandering inside a heavily armed fortress – an allegory for staying true to one’s principles by withdrawal from public (‘inner emigration’ was a phrase coined in the 1930s, describing those German writers who, opposed to the Nazis, nevertheless withdrew into public silence). I Myself Am War (2014), meanwhile, is a horrific image of a scarred and prosthetic-encased human head, perhaps a casualty of the First World War; but in this year of centenary commemoration, it’s a work that points, anxiously, to wars yet to come.

‘If we must be designated as artists at all then we are pre-war artists!’ declare Inventory in the press text. Reenergised, perhaps, by the pervasive atmosphere of crisis that has come to replace the complacency of the noughties, Inventory might still have it in them to return to the fray.

This article originally appeared in the October 2014 issue