Kerry James Marshall, Met Breuer, New York, 25 October – 29 January

The uniqueness of the Met Breuer, the Metropolitan Museum’s contemporary art division housed in the revamped former Whitney Museum building, is its ability to counterpoint work by living artists with art and artefacts from 5,000 years of storied past. That’ll be made crystal-clear by Kerry James Marshall’s exhibition Mastry, touring in augmented fashion from the MCA Chicago. Surveying the masterful American artist’s 35 years and more of painting (and more), it features 80 works, 72 of them paintings, tracing the Alabama-born artist’s virtuoso restitution of black subjectivity within painting via a compound pictorial language ranging from neoclassical portraiture to abstraction to comics. (The title refers to the artist’s comics-rooted Rythm Mastr series, 1999–present.) Marshall’s largest museum retrospective to date – which, along the way, reconvenes The Garden Project, a mid-1990s series split for two decades – would be draw enough. But complementing all this activity is Kerry James Marshall Selects, for which Marshall has picked 40 works from the Met collection (Northern Renaissance painting, Postimpressionism, African masks, midcentury American photography) to reassert his art’s wellsprings and grasp. Expect, across these two projects, the institutional equivalent of a mic drop.

Isa Genzken, Hauser Wirth & Schimmel, Los Angeles, through 31 December

Isa Genzken doesn’t lack for retrospectives, or international reach. We had hardly blinked after seeing her big show in Vienna in 2014 before another colossus opened in Berlin (arriving from Amsterdam), while her US survey toured for three years up to 2015. But for her first major Los Angeles show (in another capacious space, Hauser Wirth & Schimmel), she’s drawing on the past in a new way. In 1977, when Genzken was in her late twenties and teaching at the art academy in Düsseldorf, she got a travel grant to California and there visited Michael Asher, the legendarily stringent, often gallery-evacuating conceptualist and longtime influential teacher at CalArts. Now, looking back on that, Genzken, whose darkly vivacious post-medium practice has often focused on the galvanic powers of city life, will present a new sculptural installation that conflates a tribute to Los Angeles with a homage to Asher, who died in 2012. Her clear-cut feelings towards him may be gleaned from the exhibition title: I Love Michael Asher.

Dan Graham, Galeria Filomena Soares, Lisbon, 17 November – 7 January

Another key conceptualist Genzken met on her California excursus was Dan Graham. But saying you love Dan Graham is fairly redundant since, frankly, who doesn’t? As influential as Asher’s art in a different way, Graham’s sense of architecture is, of course, less sanguine than Genzken’s. He sees it as a Foucauldian instrument of control, as his deceptively cool pavilions with their structures of two-way mirrors, interstitial between art and architecture (and at home in galleries and the contested realm of public space), continue to assert via their intricate play of reflections, turning viewer into viewed and vice versa. Following Foucault, Graham has called these works ‘heterotypes’, cogent interruptions in the administered blur of urban living; they’re pleasurable places to hang around, but they carry a sting. Not that we’re certain he’ll produce a pavilion-related work for Lisbon, mind you, given that Graham’s practice has encompassed performance video, photography, writing and the epochal 1982–4 sociological art film Rock My Religion. But we’d be surprised if he can wholly resist the allure of Portuguese light on steel and glass. (Side note: for all his outward rationalism, Graham is also the biggest astrology nerd that ArtReview has ever met.)

Jutta Koether, Campoli Presti, London, through 12 November

Jutta Koether, who’s as much an artist/ writer as Graham (if not more so), used to write for Berlin’s Spex magazine, but when it comes to her forthcoming show at Campoli Presti, Best of Studios, we have no specs at all. Fair to say, though, that Koether has long been a proponent of so-called network painting, which is rooted in the work of her late Cologne contemporary Martin Kippenberger, and her painting – its rough-edged lyricism and layering recalling Sigmar Polke, its palette often pinkish, its outlook often punkish – reflexively emphasises the act of its own reading via a miscellany of reference points. Yet in her last show at Campoli Presti’s London branch, in 2013, Koether invoked (via Jacques Derrida’s 1969 lecture ‘The Double Session’, after which she titled the show) a notion of ‘double reading’. So whatever we did say about her latest work – an open prospect, given her historical veering into anything from musical/artistic collaboration (with Kim Gordon) to sculptural installation – there’d probably be something else to say too, and we consider ourselves off the hook.

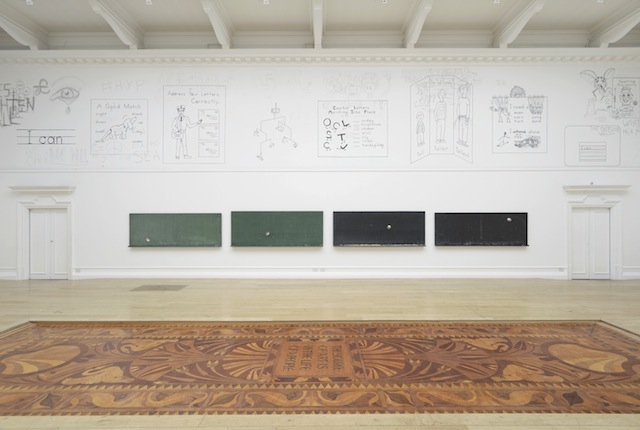

Martin Creed, Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck, through 20 November

In a recent BBC TV programme on Dada, Martin Creed was royally trounced in a portraiture faceoff with comedian Vic Reeves. (Neither of them was permitted to look while painting, but still.) He also admitted he hadn’t known, when he half-filled a room with balloons, that the Dadaists had gotten there first. His works can look like oneliners, sometimes unappetising ones (videos of people shitting and vomiting, screwed-up sheets of A4 paper). And he’s a terrible um-ing and ah-ing interviewee. But! The Wakefield-born artist/musician/choreographer is an artist of deceptively grand affect. Brought together, his works accrete into a swaying meditation on control and its limits, myriad small gestures that serve as attempts to bring order and system to life’s messiness, allied to a perpetual, almost desperate inventiveness. Here, Creed has his first solo exhibition in the ordered purlieus of Austria, where the far right is dangerously in the ascendant. Perhaps the artist’s neons (eg EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT, 1999, DON’T WORRY, 2003) will be judiciously held back.

Josh Kline, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, 4 November – 26 February

While the term ‘Postinternet’ becomes a malign historical artefact, one figure likely to survive the loosely affiliated genre’s dissolution is Josh Kline. The Philadelphia-born artist has a uniquely forceful way of compressing, and connecting, capitalised issues of the moment: state control, unbridled consumerism, rampant inequality and waste. See, for example, his hyperreal, end-of-days installation at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo (dispatched from a recent show at New York’s 47 Canal), Unemployment (2016). Here, mesh boxes and shopping trolleys, glowing from beneath, brim with silicone bottles that are either flesh-coloured or sprout human hands, and are surrounded by foetal human figures – small-business owners, mortgage loan officers, lawyers (according to the titles) – in clear plastic trash bags. As Kline himself has suggested, this is effectively sampling applied to sculpture, splicing aspects of the everyday together; it’s also the stuff of real-world nightmares.

13th Cuenca Biennial, various venues, Cuenca, 25 November – 5 February 2017

Curated by Dan Cameron, the 13th Cuenca Biennial – that’s the Cuenca in Ecuador, not the Cuenca in Spain – is, like all biennales, a temporary thing. In this case, though, that’s apt: the US curator’s IMPERMANENCIA, Mutable Art in a Materialist Society aims to outline a divide in contemporary art: between work that’s speculated on and stored in a vault, and work that is relatively ephemeral and mirrors our current situation. The title of the show might hint at which side of the line Cameron favours here; in his curatorial statement, he also suggests a sunny upside to a focus on impermanence by linking it to Buddhism. Thirteen venues house 49 participants, including Kader Attia, Cao Fei, Cevdet Erek, Hew Locke and a goodly number of Ecuadorian artists including Janeth Méndez, Damián Sinchi and Kelver Ax. The last Cuenca Biennial was deemed an installation art-filled flop; Cameron, founder of Prospect New Orleans and a veteran at mounting strong shows in tricky places, seems like a smart choice to reverse the event’s trajectory.

Roman Ondak, South London Gallery, through 6 January

Neatly, at the same time (though far, far away), Roman Ondak is setting up a show that points to both the momentary and the long-term. The Slovak artist’s previous works, exploring patterns of behaviour, have regularly gravitated towards the social, whether in setting up mysterious queues of people or, in Measuring the Universe (2007–), getting people to mark their heights on the wall to create a dark, flowing abstraction symbolising myriad individuals measuring themselves. In The Source of Art is in the Life of a People at the South London Gallery – Ondak’s first London show in a decade – for a hundred days that symbolises a hundred years, a presawn disc will be separated, daily, from an oak tree’s trunk, revealing a line drawn round one of its rings and a text describing an important historical event from the year in question. These will go on the wall, creating an expanding calendar, but also one that points up the subjectivity of historical process (this is Ondak’s view of what was important, after all.) Alongside these, meanwhile, are – among other things – blow-ups of pages from a textbook on social behaviour that the sociable artist has invited twelve-to-eighteen-year-olds in the area to daub, deface or otherwise editorialise. Someone else does the work, Tom Sawyer-style, and the result is art that mobilises open-endedness and addresses authority under the guise of largesse.

Nina Canell, Barbara Wien, Berlin, through 30 November

Also on the subject of art invested with life: for a number of years now, Nina Canell has been making sculptural work concerning, as a press text from Barbara Wien puts it, ‘the place and displacement of energy’, allowing a supposedly static form to animate, change, lose fixity – become, if you like, more like life. In the past, this has meant (among other things) sculptures set rattling by steam passing through them; electric cables chopped and suspended in tanks, suggesting the containing of a residual charge. In her third show with her Berlin gallery, Foam-Skin Insulated Jelly-Filled Vowel, Canell extends a vocabulary that’s both postminimal and anthropomorphic: coils of hollowed-out subterranean fibre optic cable look like sheaths of shed snakeskin, while another installation sets the ‘short-term memory’ of wires into motion via sine waves. Yeah, us neither, but we’re going to find out.

Edward Krasiński, Tate Liverpool, 21 October – 5 March

Generally this column focuses only on living artists. But we’re making an exception for Edward Krasiński (1925–2004), since he was himself exceptional and his first UK retrospective (at Tate Liverpool) is an occasion to be marked. A key member of the Polish avant-garde, Krasiński zoomed through various formats (graphic design, neo-Surrealism, works involving objects dangling on wires, suggesting movement), before his signature blue Scotch tape appeared. This would go on to slink horizontally across objects, all kinds of exhibiting spaces and the axonometric Intervention paintings he began making in the early 1970s; later, Krasiński moved on to making mazes. But his taping is the thing: a Dadaist provocation, a conceptualist approach equal to Daniel Buren’s stripes or Stanley Brouwn’s measurements, an infinitely resourceful approach with materials that could be carried in the pocket and bought for almost nothing. ‘I don’t know if this is art,’ Krasiński once said. ‘I know that it’s a blue Scotch tape, width 19mm, length unknown.’

This article is published in the November 2016 issue of ArtReview.