The body of an athlete is primed and engineered to excel in a narrow and specific field of movements. The body of a dancer – particularly one involved in contemporary dance – is, by contrast, primed for the greatest available range of movement; it is an expressive tool rather than a purely functional one. The more extensive the gestural vocabulary dancers can access, the more articulate their physical expression.

The evolution of dance in the last century has involved a constant transformation of the lexicon of gesture. As with a verbal vocabulary, however, the language of dance must retain the capacity to communicate – not only with the audience, but also with the performers themselves. A piece of choreography, particularly one involving multiple dancers, must be memorable and reproducible to a very precise degree.

Ka Fai releases the vocabulary of gesture from the weight of other cultural language

The question of how the vocabulary of gesture evolves and of how dancers retain the memory of a precise and convoluted sequence of unfamiliar movements is the subject of some fascination. The Wellcome Collection in London is currently exhibiting the fruit of some ten years of research into the link between mind and movement carried out by scientists from various disciplines working alongside Wayne McGregor’s Random Dance company. The exhibition touches variously on collective intelligence, the genesis and development of ideas and how technology can understand and interpret three-dimensional movements.

One study investigated how the company memorised movements for which there was no existing verbal or graphic symbolism – and in particular the strong role that visualisation played in this. Dancers talked about how their sequence of gestures created or related to a form or picture. One described how he would imagine a city laid out on the stage, across which he would pick his route, with the architecture dictating the form of his movements. These segments feel like a ‘eureka’ moment; perhaps because, as nondancers, we grasp at notions that translate dance into a vocabulary we find accessible – the language of architecture, or the gesture of a brushstroke.

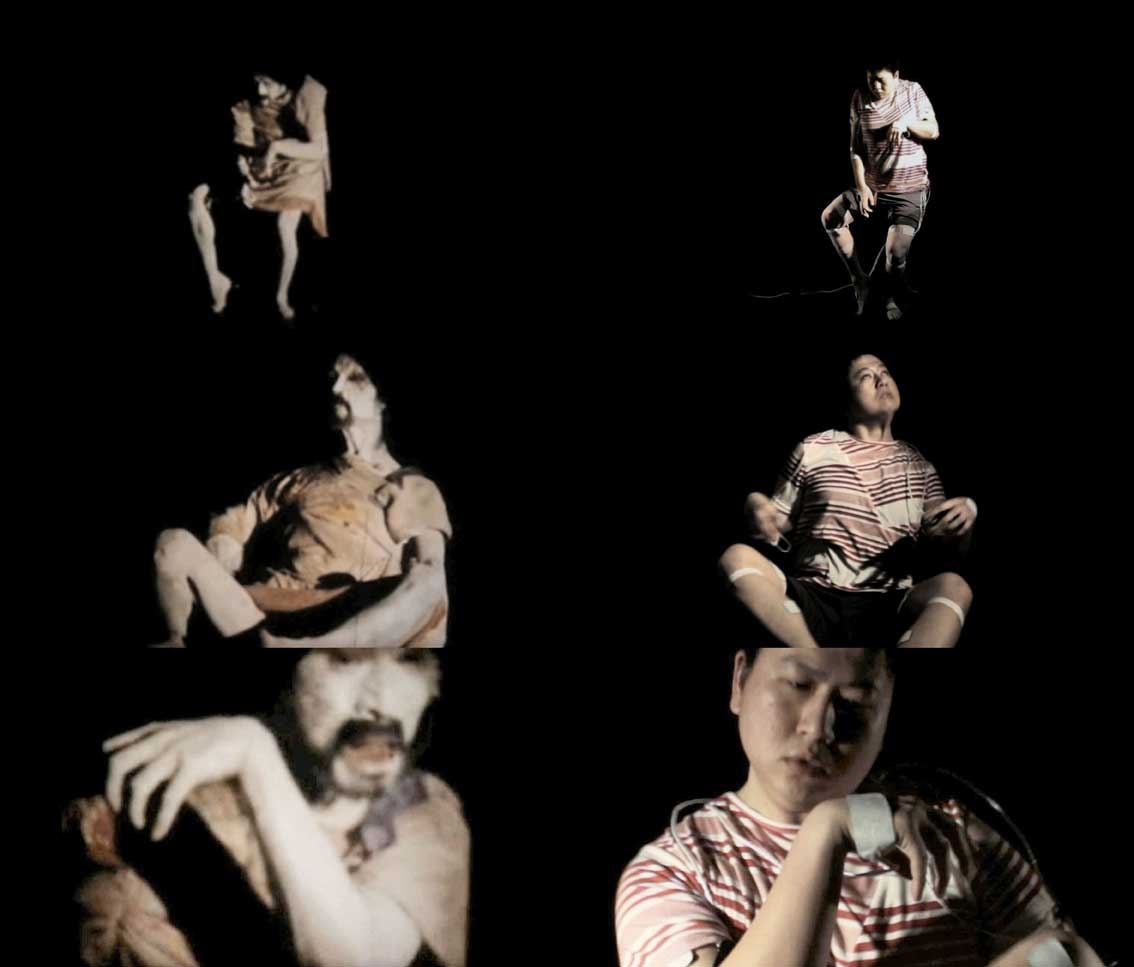

The artist and designer Choy Ka Fai (aka Ka5) has been investigating movement memory from the opposite direction – in Prospectus for a Future Body (2011) he experimented with sonic and electrical stimuli applied directly to muscle. In one part of the project – Eternal Summer Storm – we watch him mapping a sequence of movements from a 1973 performance by Tatsumi Hijikata; Ka Fai then reproduces the sequence by responding to programmed sonic vibrations stimulating his muscles.

In the final part of the project – a lecture performance called Notion: Dance Fiction – he applies similar stimulation to the body of a professional dancer, essentially electrocuting her (albeit mildly) according to choreography derived from portions of work by luminaries ranging from Pina Bausch to Pichet Klunchun.

Broken down and sequenced in such a way, choreography is eternally reproducible; taken to its most ridiculous extreme, the human body becomes a puppet, controlled by a network of electrical stimulations, and the dance sequence becomes a kind of industrial product. While there is something slightly disturbing (and indeed disturbingly comic) about this, by connecting choreography directly to muscle, and by communicating movement by creating muscle memory, Ka Fai releases the vocabulary of gesture from the weight of other cultural language. A movement is just a movement, not a metaphor.

This issue of cultural language becomes pointed in Ka Fai’s project Soft Machine (2011–), in which the artist initiates a new discourse in response to the persistence of mystification and ‘exoticism’ in Western representations of contemporary dance from Asia. Involving dancers in China, Japan, India, Indonesia and Singapore, Soft Machine is an immense project, encompassing short documentary films, collaborative performances and lectures, the first elements of which will be shown in Singapore in November. The attempt to examine the vocabulary of gesture on its own terms becomes a task of Fibonacci-esque complexity, spiralling in from continent to country to city to scene to YouTube references to in-jokes. Having stripped gesture of its cultural weight in Prospectus…, here Ka Fai builds it back up, layer by layer, describing the apparently endlessly eloquent complexity of human movement.

This article was first published in the November 2013 issue.