This new series, Eternal Returns, seeks to republish (and annotate) key texts that have influenced art and the thinking around art. Here, Gombrich explores the stylistic categories of art history and their origins in Renaissance ideals, while ArtReview inserts a few thoughts on the influence of Gombrich’s thinking in light of current debates on representation and decolonisation.

It is well known that many of the stylistic terms with which the art historian [Here Gombrich is referring to acolytes of art history in the sense that they are obsessed with a history that is inherently European. And equally obsessed by the Renaissance as the turning point of modernity, which was, in general terms, the received wisdom of the time.] operates began their career in the vocabulary of critical abuse. ‘Gothic’ once had the same connotation as our ‘vandalism’ as a mark of barbaric insensitivity to beauty, ‘baroque’ still figures in the Pocket Oxford Dictionary [This is an antiquated item from an age in which dictionaries were physical objects that one might want to be pocket-size in case one got stuck midsentence and needed to look something up. Today dictionaries are digital – unlimited by the restrictions of print costs and clothing fashion – and designed to be read on mobile phone screens.] of 1934 with the primary meaning of ‘grotesque, whimsical’, and even the word ‘impressionist’ was coined by a critic in derision. We are proud of having stripped these terms of their derogatory overtones. We believe we can now use them in a purely neutral, purely descriptive sense [These days, when it is generally accepted that no word is neutral and that all use of language is an expression of some form of prejudice, this belief might well be seen as quaint (at best) and delusional (at worst).] to denote certain styles or periods we neither wish to condemn nor to praise. Up to a point, of course, our belief is justified. We can speak of gothic ivories, baroque organ-lofts or impressionist paintings with a very good chance of describing a class of works which our colleagues could identify with ease. But our assurance breaks down when it comes to theoretical discussions about the limits of these categories. Is Ghiberti ‘gothic’, is Rembrandt ‘baroque’, is Degas an ‘impressionist’? Debates of this kind can become stuck in sterile verbalism, and yet they sometimes have their use if they remind us of the simple fact that the labels we use must of necessity differ from those which our colleagues who work in the field of entomology fix on their beetles or butterflies. In the discussion of works of art description can never be completely divorced from criticism. [By which Gombrich sets up what might be a fundamental difference between art history and art criticism, where critics write about the particular things, and historians go around gathering art and putting it all into categories, like ‘Young British art’, or ‘post-Internet art’, or ‘Queer aesthetics’ and so on. Gombrich suggests that such categories, while apparently descriptive, are actually based on value judgements made long before, about what to value and what might be worthless.] The perplexities which art historians have encountered in their debates about styles and periods are due to this lack of distinction between form and norm. [Gombrich here, with some degree of prescience, has tapped into some of the issues that will dominate art-historical discourse in our age. Today of course, the prevailing winds of art history in particular and cultural studies in general plot a course in which labelling anything reflects conscious or unconscious prejudice and is best avoided. As, more often than not, is saying anything at all.]

Benedetto Croce (right) was an Italian historian, philosopher (famously the author of a commentary on Hegel) and politician. Having initially supported Benito Mussolini’s fascist government, he went on to be instrumental in the return of democracy to Italy. In that sense he was living proof of the problematics of absolute judgement. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature no less than 16 times.

1. Classification and Its Discontents

There can be few lovers of art who have never felt impatient of the academic art historian and his concern with labels and pigeonholes. Since most art historians are also lovers of art [Interestingly Gombrich arrives at something of a paradox here. Having distinguished between lovers of art and art historians in the previous sentence, he now attempts an unlikely reconciliation in this one. The fundamental distinction seems to be one that early ArtReview contributor Peter Reyner Banham would articulate as the distinction between ‘common’ and ‘learned’ sense.] they will have every sympathy with this reaction, of which Benedetto Croce was the most persuasive spokesman. To Croce it seemed that stylistic categories could only do violence to what he so aptly called the ‘insularity’ of each individual and incommensurable work of art. But, plausible as this argument is, it would clearly lead to an atomization of our world. Not only paintings but even plants and the proverbial beetles are all individuals, all presumably unique; to all of them applies the scholastic tag ‘individuum est ineffabile’: the individual thing cannot be caught in the network of our language, for language must needs operate with concepts, universals. The way out of this dilemma is not a withdrawal into nominalism, the refusal to use any words except names of individuals. [Typically of his writing, here Gombrich is moving from discussions of popular sensibilities to high-end academia, anticipating some of the problems that would fascinate analytic philosophers and logicians such as Saul Kripke (in his 1970 Princeton Lecture Series, later published, in 1980, as Naming and Necessity). The ripples of which continue to wash over critical writing to this day, in particular in relation to the necessity or otherwise of the evils Gombrich goes on to describe in the sentence that follows.] Like all users of language the art historian has rather to admit that classification is a necessary tool, even though it may be a necessary evil. Provided he never forgets that, like all language, it is a man-made thing which man can also adjust or change, it will serve him quite well in his day-to-day work. [These days manmade things have been recognised to be all bad. It’s good to chip away at the monolithic heaviness of classifications, since they aren’t describing realities set in stone, but only interpretations of what artworks mean and have meant in the past. At the same time, if every art-historical classification is temporary, then revising them becomes an endless game, changing with the prevailing fashion. Why are there so many exhibitions about ‘overlooked women artists’, for example?]

2. The Origins of Stylistic Terminology

For the student of style, experimentation with these dichotomies is relevant if it prepares him for the insight that the variety of stylistic labels with which the art historian usually appears to be operating is in a sense misleading. That procession of styles and periods known to every beginner – Classic, Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Mannerist, Baroque, Rococo, Neo-Classical and Romantic – represents only a series of masks for two categories, the classical and the non-classical. [Here Gombrich is doing his own pigeonholing, sweeping up a sequence of styles and putting them into one box, marked ‘classical’. This is itself an act of history-writing based on the historical distance between him and what he’s discussing. What happens after Romantic art, after all?]

That ‘Gothic’ meant nothing else to Vasari than the style of the hordes who destroyed the Roman Empire is too well known to need elaboration. What is perhaps less well known is the fact that in describing this depraved manner of a non-classical method of building, Vasari himself derived his concepts and his categories of corruption from the only classical book of normative criticism in which he could find such a description ready-made – Vitruvius On Architecture. [Here Gombrich doubles down on the inadequacy of language when it comes to describing difference and, were such a thing actually to exist, novelty. Vitruvius was a Roman architect active during the first century BCE. He became famous because his book De architectura is the only instructional tome known to have survived from this time. It is to architecture what the Bible is to Judeo-Christians.] Vitruvius of course nowhere describes any style of building outside the classical tradition, but there is one famous critical condemnation of a style in the chapter on wall-decoration, where he attacks the licence and illogicality of the decorative style fashionable in his age. He contrasts this style with the rational method of representing real or plausible architectural constructions.

‘But these [subjects] which were imitations based upon reality are now disdained by the improper taste of the present. On the stucco are monsters rather than definite representations taken from definite things. Instead of columns there rise up stalks; instead of gables, striped panels with curled leaves and volutes. Candelabra uphold pictured shrines and above the summits of these, clusters of thin stalks rise from their roots in tendrils with little figures seated upon them at random. Again, slender stalks with heads of men and animals attached to half the body.

‘Such things neither are, nor can be, nor have been. On these lines the new fashions compel bad judges to condemn good craftsmanship for dullness. For how can a reed actually sustain a roof, or a candelabrum the ornaments of a gable, or a soft and slender stalk a seated statue, or how can flowers and half-statues rise alternatively from roots and stalks? Yet when people view these falsehoods, they approve rather than condemn.’

Basically Vitruvius, in the first century BCE, is doing art criticism still recognisable, in its basic forms, even today. He’s saying that some art is crap, and that other people don’t get that it’s crap, and instead say that it’s good. The fools. After all, how can flowers and half statues rise alternatively from roots and stalks? It’s crazy stuff, and looks stupid. Unless you’re one of the Surrealists, who were often very much into classical art. And nobody got them either at the time. Anyway, go Vitrivius. BTW, these days only a critic with a deathwish would call anything improper or monstruous. Not just because what’s improper today will become proper tomorrow (this is the point of Gombrich’s essay) or what’s monstrous today will be a thing of beauty tomorrow, but also because we are generally beginning to shun negative language. Even though, as Gombrich and ourselves have indicated earlier, we should know that all language is violence. So what’s to worry about?

Turning from this description to Vasari’s image of the building habits of the northern barbarians, we discover that the origins of the stylistic category of the Gothic do not lie in any morphological observation of buildings, but entirely in the prefabricated catalogue of sins which Vasari took over from his authority.

‘There is another kind of work, called German… which could well be called Confusion or Disorder [Today such stereotyping might well be considered racist. Particularly when coming from an Italian.] instead, for in their buildings – so numerous that they have infected the whole world – they made the doorways decorated with columns slender and contorted like a vine, not strong enough to bear the slightest weight; in the same way on the facades and other decorated parts they made a malediction of little tabernacles one above another, with so many pyramids and points and leaves that it seems impossible for it to support itself, let alone other weights. They look more as if they were made of paper than of stone or marble. And in these work s they made so many projections, gaps, brackets and curlecues that they put them out of proportion; and often, with one thing put on top of another, they go so high that the top of a door touches the roof. This manner was invented by the Goths…’

I do not share that sense of superiority which marks so many characterizations of Vasari. His work amply shows that he could give credit even to buildings or paintings which he found less than perfect from his point of view. We should rather envy Vasari his conviction that he could recognize perfection [Perfection, for Vasari, seems intimately connected to deluded ideas of ‘truthfulness’. Even though everyone knew and continues to know that all good art relies on deception. Which is to say, that there’s an element of self-deception present here. But that perhaps such delusions are fundamental to the condition of being either an art historian or an art lover. Which may or may not be the same thing, as was suggested earlier.] when he saw it and that this perfection could be formulated with the help of Vitruvian categories – the famous standard of regola, ordine, misura, disegno e maniera laid down in his Preface to the Third Part and admirably exemplified in his Lives of Leonardo and Bramante.

These normative attitudes hardened into an inflexible dogma only when the stylistic categories were used by critics across the Alps who wanted to pit the classic ideals of perfection against local traditions. [This, basically, continues to define what is called art and what is not deemed worthy of the category, whether that be ‘craft’, vernacular stylings or local knickknackery.] Gothic then became synonymous with that bad taste that had ruled in the Dark Ages, before the light of the new style was carried from Italy to the north. [Interestingly, every age seems to want to set itself as superior to whatever went before it. Then hipsters get involved and revive the stuff that the uptight rulemakers say is bad. Which is why Britain is full of old buildings that look like they’re out of Harry Potter. But this usefully reminds us that while we too may think that old art is rubbish, we may not turn out to be right.]

Jacob Burckhardt (centre) was a Swiss art historian who was born and lived in Basel his entire life. Before it was home to an art fair. Der Cicerone (1855) was a comprehensive study of Italian art, which, in the context of Vasari’s earlier quoted comments about those on ‘the other side’ of the Alps might be considered ironic.

John Ruskin (right) was the most influential British art historian and art critic of the nineteenth century. Wellcome Collection. CC By 4.0.

3. Neutrality and Criticism

It is not my intention to give a full account of the gradual rehabilitation of these various styles or of the forces of historical tolerance and nationalist pride that contributed to the rejection of Vitruvian monopolism. What matters in the present context is only that those who questioned the norm still accepted the categories to which it had given rise. [Again, Gombrich’s text is prescient. This is the fundamental issue that haunts all those claiming to decolonise museums today.] Like Warburton in the eighteenth century, nineteenth century historians usually acknowledged the unclassical character of the styles they wanted to defend, but they stressed some compensating virtue. Mediaeval styles may have been less beautiful than the Vitruvian norm demands, but they are more devout, more honest or more strong, and surely piety, honesty and strength count for more than mere mechanical orderliness? This is Ruskin’s approach. [Well, it’s all a matter of taste, isn’t it? Or is it? But what is taste?] Burckhardt’s tentative vindication of the Baroque in the Cicerone is not very different when he writes about baroque church facades: ‘… yet they move the beholder sometimes as a pure fiction, in spite of their frequently depraved manner of expression…’ The phases by which this tolerance for the unclassical styles became a partiality in their favour belong to the history of taste and fashions rather than to the problems of historiography. What concerns us is the claim which arose in the nineteenth century that the historian can ignore the norm and look at the succession of these styles without any bias; that he can, in the words of Hippolyte Taine, approach the varieties of past creations much as the botanist approaches his material, without caring whether the flowers he describes are beautiful or ugly, poisonous or wholesome. [A belief in this claim is, once again, pretty much the norm for art history today.]

It is not surprising that this approach to the styles of the past seemed plausible to the nineteenth century, for its practice had kept step with its theory. Nineteenth century architects and decorators used the forms of earlier styles with sublime impartiality, selecting here the Romanesque repertory for a railway station, there a Baroque stucco pattern for a theatre [Here Gombrich anticipates the artistic style of postmodernism, while suggesting in the process his adherence to the belief that there is no such thing as newness. That nothing comes from nothing. Which you might consider to be an argument for the importance of history or, depending on your outlook, an argument against the same. Because, as ArtReview has learned over the past 75 years, everyone always desires the shock of the new. However imaginary that shock might be. But perhaps this too gets to one of the fundamental properties of art – that it is all built upon desire. And any attempt to remove emotion from the equation is a fool’s errand.] No wonder that the idea gained ground that styles are distinguished by certain recognizable morphological characteristics, such as the pointed arch for Gothic and the rocaille for the Rococo, and that these terms could safely be applied stripped of their normative connotation.

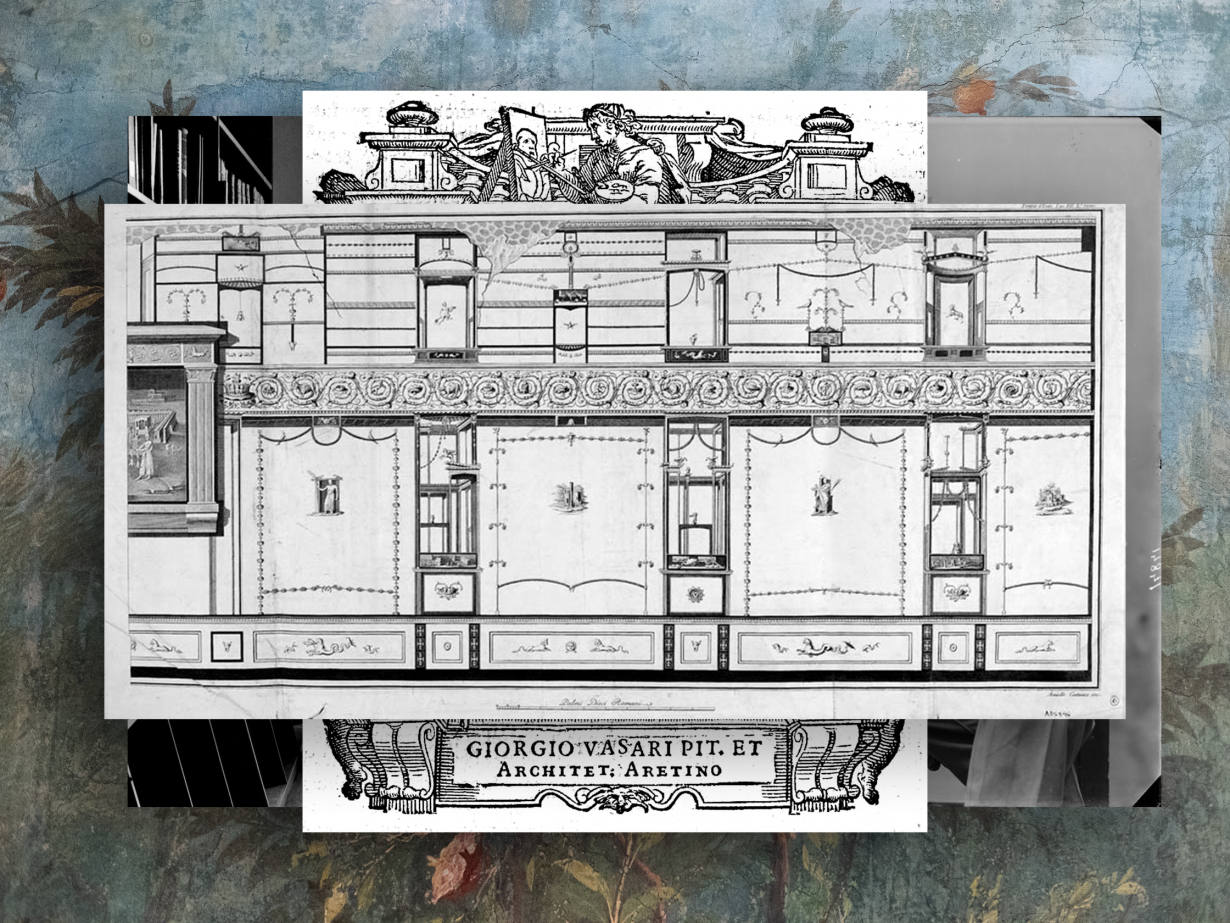

Even this morphological approach has its roots in Vitruvius. It derives from his treatment of the orders. Doric, Ionian and Corinthian are such repertories of forms, easily recognizable by certain specified characteristics and easily applied by any architect who can use a patternbook. Why should this range not be extended to embrace the Gothic or the Baroque order as well, and thus merely increase the languages of form the architect learns to speak?

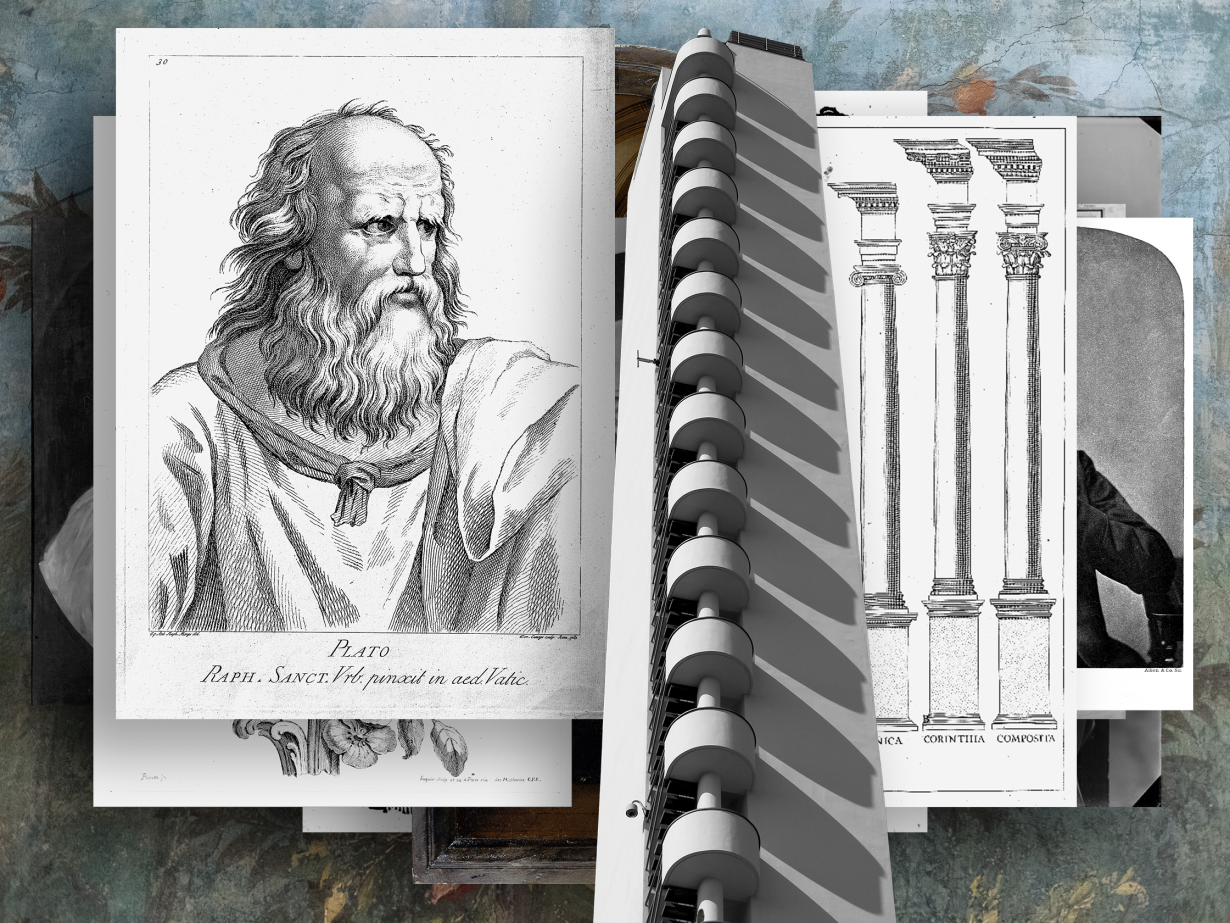

Plate from Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (right), The Five Orders of Architecture, 1562

As long as the labels for styles were mainly applied to architecture and patterns in such practical contexts things went reasonably well. But the defenders of these styles had higher ambitions. They wanted to advocate the unclassical styles as systems in their own right embodying alternative values, if not philosophies. The Gothic style was superior to the Renaissance not because it built in pointed arches but because it embodies the Age of Faith which the pagans of the Renaissance could not appreciate. Styles, in other words, were seen as manifestations of that spirit of the age which had risen to metaphysical status in Hegel’s vision of history. [There’s a lot to be said for trying to reinvest the art of the past with the meaning it might have held for those who originally made it. It’s an optimistic belief in being able to understand human beings in the past. Conversely, it can lead to projecting one’s own beliefs and value judgements onto the past. Like saying that Shakespeare must have been a racist. Which he was. Or was he? See how easy it is? These days it is impossible to write anything about art that does not treat it as a manifestation of the spirit of the age, or an embodiment of a philosophy or ideology.] This spirit in its unfolding manifested itself not only in certain architectural forms, it also gained shape in the painting, sculpture and pattern of the age, which pointed to the same outlook that moulded the literature, the politics and the philosophy of the period. To this approach such morphological marks of recognition as the presence of a rocaille for the rococo or the rib for the Gothic appeared hopelessly ‘superficial’. [Here Gombrich is being snarky about the possibility of big ideas, and grand narratives of history, which is perhaps understandable given how much Europeans had suffered in the twentieth century in the name of grand narratives. But still, that’s not necessarily Hegel’s fault.] There must be something that all works of art created in these distinct periods of human history had in common, they must share some profound quality or essence which characterizes all manifestations of the Gothic or the Baroque. K.R. Popper has taught me to recognize in this demand for an ‘essential’ definition a remnant of Aristotle’s conception of scientific procedure. It was Aristotle, the great biologist, who conceived of the work of the scientist as basically a work of classification and description such as the zoologist or botanist is apt to perform, and it was he who believed that these classes are not created but found in nature through the process of induction and intellectual intuition. Looking at many trees we find some that have structural features in common and form a genus or a species. This species manifests itself in every individual tree as far as resistant matter allows, and though individual trees may therefore differ, their differences are merely ‘accidental’ compared to the essence they share. One may admit that Aristotle’s procedure was a brilliant solution of the problem of universals as this had been proposed by Plato. No longer need we look for the idea of the horse or the pinetree in some remote world beyond the heavens, we find it at work within the individual as its entelechy and its inherent form. But whatever the value of Aristotle’s procedure for the history of biology, the grip it retained on the humanities even when science had long discarded this mode of thought provides ample food for reflection. [The later work of the philosopher Michel Foucault, on systems of authority, control and classification, would, of course, undo this grip. But what Gombrich is onto here continues to concern the distinction between common and learned sense, and the desire of the learned to preach to and be followed by the commoners. As a form of validation. In a sense, then, Gombrich is anticipating the age of social media. While perhaps inadvertently demonstrating that nothing is new. Again. Which might, in turn, be said to be a demonstration of his point, and a return to the earlier subject of the relationship of form to meaning.] For the discussions which came into fashion during the last hundred years about the true essence of the Renaissance, the Gothic or the Baroque betray in most cases an uncritical acceptance of Aristotelian essentialism. They presuppose that the historian who looks at a sufficient number of works created in the period concerned will gradually arrive at an intellectual intuition of the indwelling essence that distinguishes these works from all others, just as pinetrees are distinguished from oaks. Indeed, if the historian’s eye is sufficiently sharp and his intuition sufficiently profound, he will even penetrate beyond the essence of the species to that of the genus; he will be able to grasp not only the common structural features of all gothic paintings and statues, but also the higher unity that links them with gothic literature, law and philosophy.

I side with those philosophers who, like Sir Karl Popper, look with suspicion at what he calls Essentialism, but wherever one may stand in this modern battle of realists versus nominalists it is obvious that categories and classes which serve very well for one purpose may break down when used in a different context. The normative connotations of our stylistic terms cannot simply be converted into morphological ones – for you can never get more out of your classification than you put into it. The cook may divide fungi into edible mushrooms and poisonous toadstools; these are the categories that matter to him. He forgets, even if he ever cared, that there may be fungi which are neither edible nor poisonous. But a botanist who based his taxonomy of fungi on these distinctions and then married them to some other method of classification would surely fail to produce anything useful. [It is unclear how Gombrich intends to convert the idea of usefulness from the life and death example of botany into something similar in the field of art history. Perhaps it’s merely to avoid this problem that he has turned (once again) to botany in the first place. Or perhaps it’s another concession that art history struggles to appeal to the common sense.]

I do not imply that the origin of a word must always be respected by those who apply it. The discovery that the Gothic style has nothing to do with the Goths need not concern the art historian, who still finds the label useful. What should concern him in the history of the term, I think, is its original lack of differentiation. The stylistic names I enumerated did not arise from a consideration of particular features, as do Vitruvius’ terms for the orders; they are negative terms like the Greek term Barbarian, which means no more than a non-Greek.

Helsinki Olympic Stadium Tower (right). CC BY-SA 2.5.

If I may introduce a harmless term, I should like to call such labels terms of exclusion. [In the age of inclusion, this has become the primary problem of both art history and museology. You can’t label something without making it distinct from something else. And if things are distinct they cannot be the same or stand on the same level ground.] Their frequency in our languages illustrates the basic need in man to distinguish ‘us’ from ‘them’, the world of the familiar from the vast, unarticulated world outside that does not belong and is rejected.

It is no accident, I believe, that the various terms for non-classical styles turn out to be such terms of exclusion. It was the classical tradition of normative aesthetics that first formulated some rules of art, and such rules are most easily formulated negatively as a catalogue of sins to be avoided. Just as most of the Ten Commandments are really prohibitions, so most rules of art and of style are warnings against certain sins. We have heard some of these sins characterized in the previous quotations – the disharmonious, the arbitrary and the illogical must be taboo to those who follow the classical canon. There are many more in the writings of normative critics from Alberti via Vasari to Bellori or Félibien. Do not overcrowd your pictures, do not use too much gold, do not seek out difficult postures for their own sake; avoid harsh contours, avoid the ugly, the indecorous and the ignoble. Indeed it might be argued that what ultimately killed the classical ideal was that the sins to be avoided multiplied till the artist’s freedom was confined to an ever narrowing space; [One might argue that a similar restriction on artistic freedom is being enacted by a form of moral policing in which the sins of today are a failure to support the ‘correct’ political or ethical cause.] all he dared to do in the end was insipid repetition of safe solutions. After this, there was only one sin to be avoided in art, that of being academic. In our exhibitions today we see the most bewildering variety of forms and experiments. Anyone who wanted to find some morphological feature that united Alberto Burri with Salvador Dali and Francis Bacon with Capogrossi would be hard put to it, but it would be easy to see that they all want to avoid being academic; they would all have displeased Bellori and would have welcomed his condemnation.

It is no accident, therefore, that the terminology of art history was so largely built on words denoting some principle of exclusion. Most movements in art erect some new taboo, some new negative principle, such as the banishing from painting by the impressionists of all ‘anecdotal’ elements. The positive slogans and shibboleths which we read in artists’ or critics’ manifestos past or present are usually much less well defined. Take the term ‘functionalism’ in twentieth-century architecture. We know by now that there are many ways of planning or building which may be called functional and that this demand alone will never solve all the architect’s problems. But the immediate effect of the slogan was to ban all ornament in architecture as non-functional and therefore taboo. What unites the most disparate schools of architecture in this century is this common aversion to a particular tradition.

Maybe we would make more progress in the study of styles if we looked out for such principles of exclusion, the sins any particular style wants to avoid, than if we continue to look for the common structure or essence of all the works produced in a certain period. [Here the prophet describes precisely what curators and art historians attached to Western institutions are frantically trying to do today. Go Ernst!]

Abridged and annotated by J. J. Charlesworth and Mark Rappolt

Abridged extract from Gombrich on the Renaissance Volume 1: Norm and Form by E. H. Gombrich, published by Phaidon