The curator of this year’s edition talks to ArtReview about the realities of largescale exhibitions in the postglobal age

Over the past three decades, the Gwangju Biennale has become one of Asia’s most influential largescale art events. Uniquely it has its own permanent gallery and was founded to commemorate the pro-democracy movement that emerged from the city in 1980. Bourriaud, a French curator who was one of the founding directors of Paris’s Palais de Tokyo and who is best known for setting out the theory behind the Relational Aesthetics movement of the 1990s, talks to ArtReview about the realities of largescale exhibitions in the postglobal age and what he’s got up his sleeve.

ArtReview Perhaps we could begin by talking about the theme of this year’s Gwangju Biennale, pansori, which, in a sense, reaches into the past (in the sense of tradition) in order to look at the present.

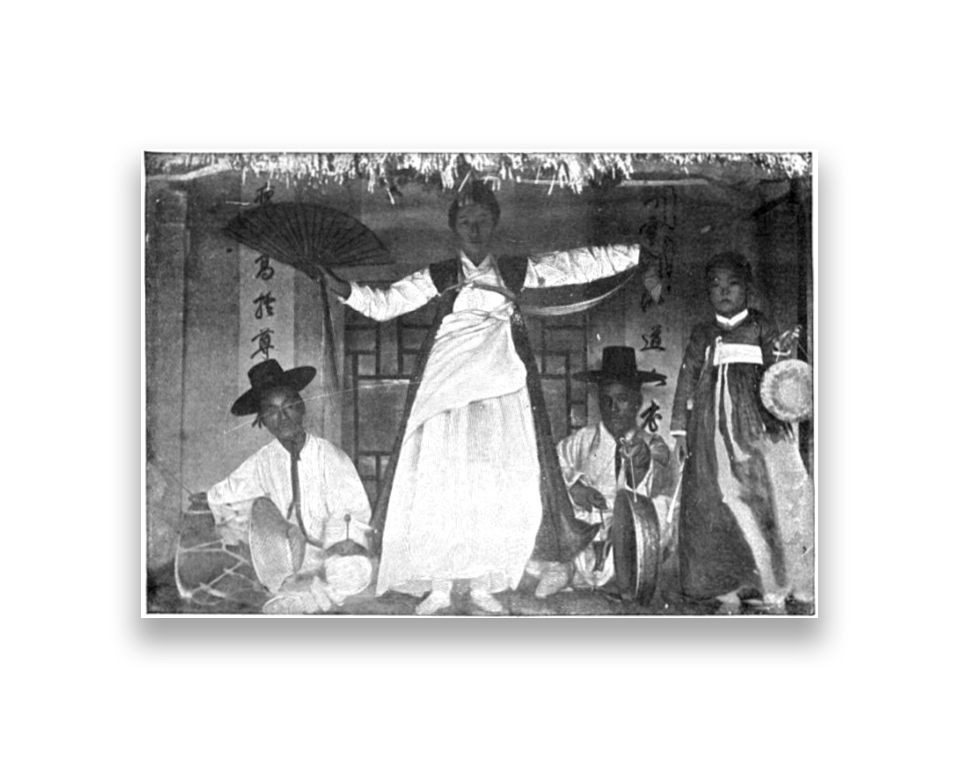

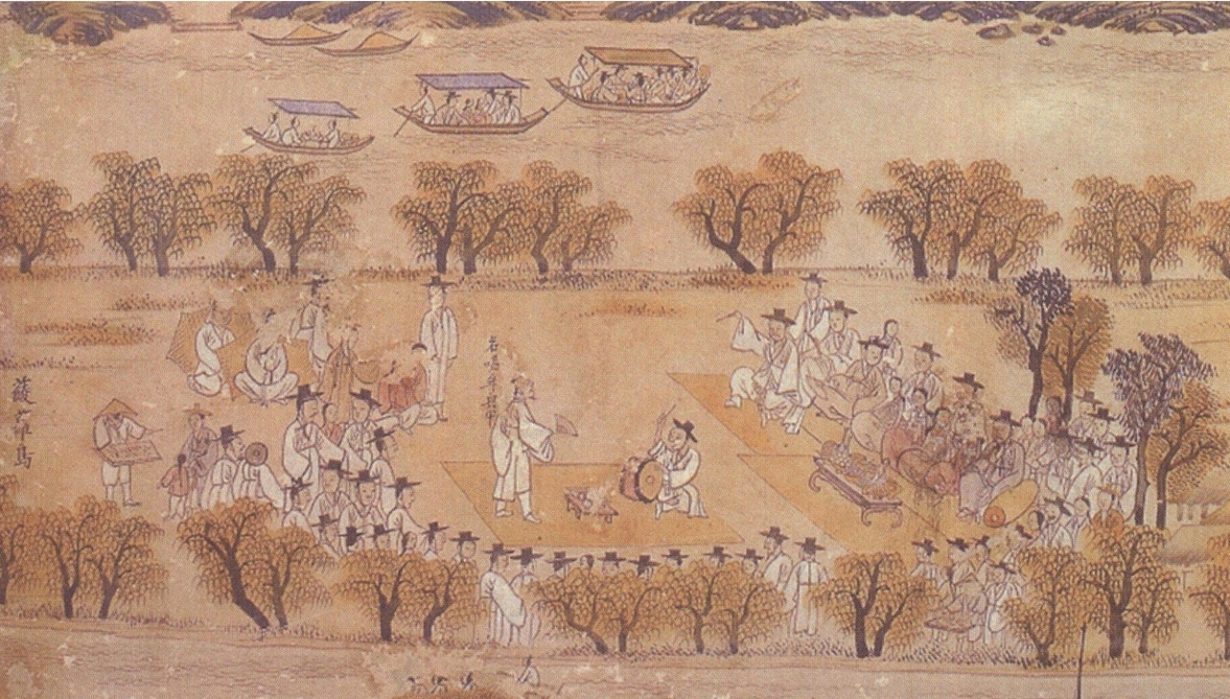

Nicolas Bourriaud I really believe that as a biennial is a temporary gathering of people coming from all horizons, it needs to be very strongly anchored in the place in which it is located. During my research, I learned about this really typically Korean musical form – pansori – that is a kind of minimalistic opera featuring poetry and drums. The form, with one singer and one drummer, appeared during the late seventeenth century in the south of Korea, making it super-local to Gwangju, in order to accompany shamanistic rituals. Then, as the centuries passed, it became more of a popular form of entertainment throughout Korea.

It’s very historical, as you said, and it’s true that it’s another kind of anchor, linking to the history of shamanism. Shamanism is precisely a way of exploring different spatial spheres. The theme of the exhibition, ultimately, is space. I decided to explore a very common, almost banal topic in the history of art. I wanted to look at climate change and the Anthropocene era from a different point of view. And then to link space to sound. So, the exhibition is subtitled A Soundscape of the 21st Century. Because any landscape is also a soundscape, but we seem to forget that.

There is an interview with Vinciane Despret, a philosopher of science, in the catalogue; she explains how birds territorialise space through singing. I link it to the way that when people migrate, for example, when you’re in exile, you tend to listen to sounds from your home country. The link between sounds and space and between songs and territory is ancient. And that’s the way I wanted to explore this.

AR It also avoids the association with space and the things that humans make – building, borders, construction…

NB Absolutely. Space can be the apartment you live in, but it can also be a cosmic space and a scientific understanding of space, as much as it can be a social space, the way in which our societies are divided and allow some people to have a space and others not to have space. It’s a geographic but also political and historical topic.

AR It also leads to this general or popular idea of a biennial as something that occupies a lot of space: the megastructure of exhibitions, if you like. Which in times of greater environmental consciousness, among other things, is something of an issue. Are these also some of the things that you are attempting to rethink in the show?

NB In a way, the theme of space, and the link between space and sound, impacted the structuration of the biennial. Visitors will enter the exhibitions through a very long, dark tunnel, where a sound piece by Emeka Ogboh will take them exactly to the position of being in the streets of Lagos and its markets. It’s a deep, very dense soundscape. The first floor corresponds to this impression of saturation, actually. It’s almost claustrophobic. The more you go throughout the different floors of the exhibition, the more the space will open up: the last floor, the fifth floor, will be devoted to the infinitely small.

I want visitors to be taken from a point A to a point Z, so the exhibition is really structured in visual sequences. In that sense, the way the theme impacts the structure of the exhibition is in its operatic dimension. I want to display the works as if visitors were caught in a movie, in a way, experiencing sequence after sequence, and different atmospheres for each floor and artwork that answer each other in a dialogical mode.

AR I guess there’s a sense in which the history of Gwangju itself can be a little claustrophobic and lead to a feeling sometimes, with the biennale, that it’s trapped in stasis because of that. Is that something you felt you had to overcome?

NB It’s impossible to escape from it, because the Gwangju Biennale was actually created to commemorate the pro-democracy uprising of the 1980s. It’s an aesthetic answer to the political, which it’s actually more or less in the same tone of every time. The Gwangju Biennale is the emanation of this political struggle. For me, that is really important. What’s different as opposed to many previous editions of the biennale is that I don’t multiply the venues all over the city. I decided to invest in one place, one neighbourhood, which is called Yangnim, and create a walkable route with a dozen venues, each one devoted to one artist. It’s a way to visit via the heart of one neighbourhood.

We’ve got a former police station that will be occupied by Saâdane Afif, Mira Mann is transforming a mysterious abandoned house, Marina Rosenfeld’s work is installed in an art studio. I wanted to really understand the urban logics of one neighborhood.

AR In one of the texts published in advance of the exhibition, you make reference to pansori and its relation to the voice of subaltern.

NB That’s one of the possible translations of pansori. Literally it’s ‘the sound of the market place’, the noise of gathering. Pansori means noise, rumour. It is a lyrical expression of people who don’t have a voice in public debate. That’s why also it has a social and political dimension, which gives shape to the exhibition.

AR What do you mean by ‘shape’?

NB I think, for me, the way in which any operatic form is a dialogue between music and narrative, forms and subtitles, is a good model for a collective exhibition.

AR Does that mean that the art itself takes on a more abstract form than normal?

NB It’s really expressing a strong statement about the state we live in, or artists who are able to investigate spaces, like Na Mira, Kandis Williams or Saâdane Afif. Hyewon Kwon worked upon the case of Jeju Island in the southwest of Korea. It’s both how do artists express space in their way of working or the representation they are producing or their ability to investigate social space or geographical issues.

AR That obviously has a political dimension as well.

NB Yes, of course.

AR Do you see that dimension as urgent right now in terms of people creating and occupying space?

NB I think what is really urgent, what is a political emergency, is to get from the artist today accurate representations of the changing world we live in. What are the emerging stakes? In which way are their works responding to the concrete modifications that climate change is introducing into our lives, in terms of space, time, social organisation?

The political emergency for artists, first of all, is about their practice: which kind of art is the contemporary of climate change? Are they in line with their times?

AR One of the big questions about these types of projects revolves around what kind of ‘real’ agency art has within these discourses: we can talk about change or doing this or that, but art itself can’t perform those changes. I wonder where the agency lies with this.

NB The question is not to replace politics but to contribute to politics. It’s totally different. Here, art has a really important role to play to modify our consciousness, and the general awareness of the situation. Here, the artist has a really important role to play. It may not be spectacular. But it might actually be as efficient as the different COP21, 22, and 23s that we went through, which were not exactly followed by spectacular change.

AR You are optimistic about the role of art in these discussions?

NB Yes. I’m not necessarily optimistic about the evolution of the planet, but I’m optimistic about the way art plays its role in this process of awareness. I see an almost planetary consciousness rising at the moment.

AR Do you feel that biennial-type art exhibitions or largescale art exhibitions have to adapt themselves to the message in a way? In terms of shipping costs, environmental damage, that these structures need reforming in and of themselves?

NB Well, the rule is to try to limit as much as possible the environmental costs of any of these events, obviously.

AR Does that change the view in terms of the number of international artists versus local artists?

NB This has to be balanced with another political danger, the closure of every national scene upon itself. I think that’s just as dangerous as the environmental cost of such a manifestation.

The 15th Gwangju Biennale, Pansori: A Soundscape for the 21st Century takes place 7 September–1 December

This interview features in the ArtReview Korea Supplement, a special publication celebrating contemporary Korean art, supported by Korea Arts Management Service