Extraction, value systems and the potential for transformation drive the ‘material storytelling’ in Nicholas Mangan’s films and sculptures

Australia and its role in the Pacific – as a settler colony built on resource extraction, as the world’s second largest coal exporter, as a nation-state exercising geopolitical influence on its neighbours – is a recurring motif across Nicholas Mangan’s oeuvre. In the Melbourne-based artist’s most recent and ongoing project, Core-Coralations (2021–), the world’s largest and longest reef complex, the Great Barrier Reef, is the locus for a speculation on the relationship between human and coral futures. This work, like many of those that preceded it, combines both film and sculpture, and is shaped by Mangan’s travels to the coral-rich Heron Island, as well as his encounters with coral ‘core’ specimens in the SeaSim research lab in Townsville, Queensland.

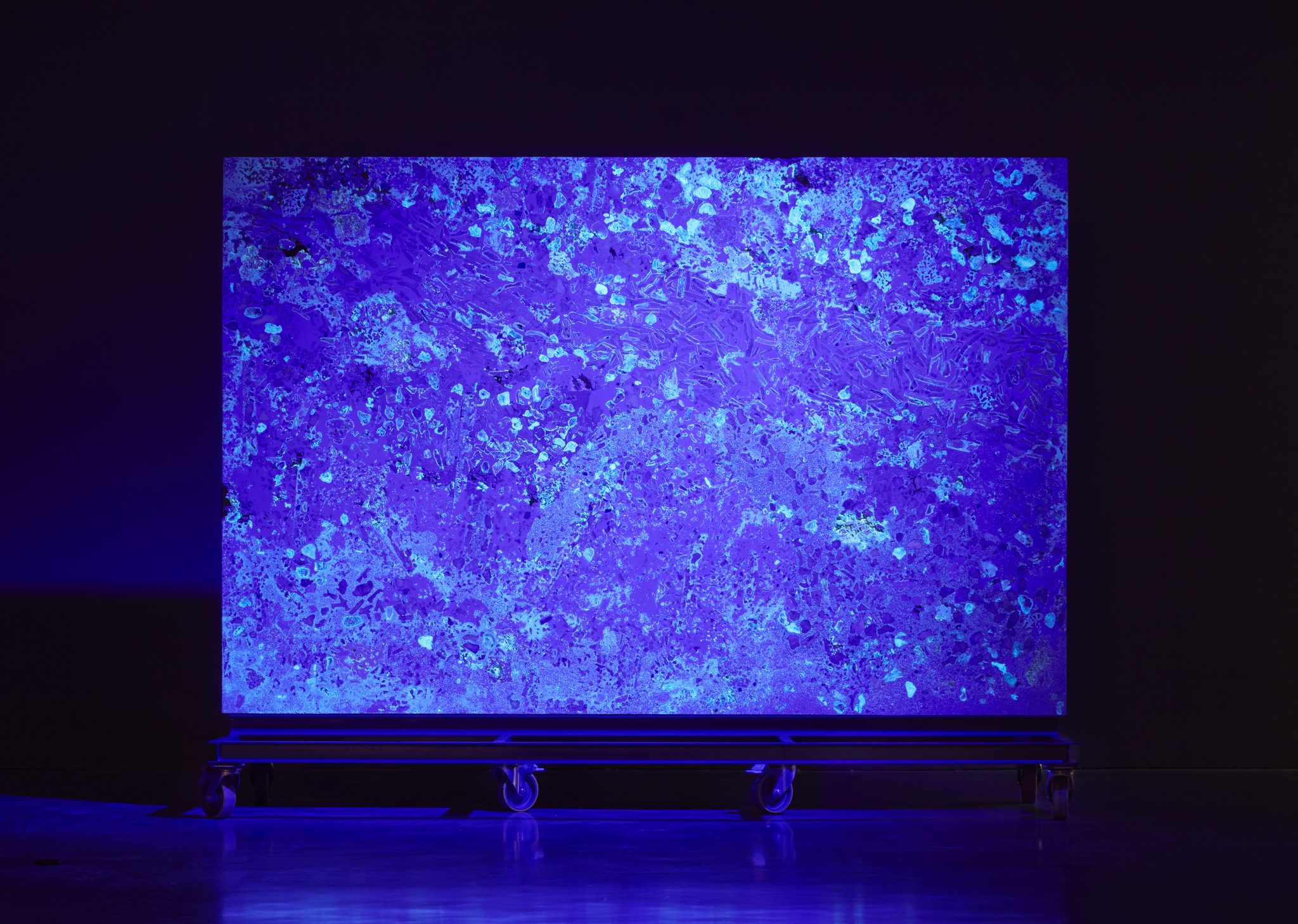

Coral is acutely impacted by rising sea temperatures, which are currently turbocharged by unchecked global heating, and the Reef has experienced an unprecedented five mass bleaching events since 2016 (the most widespread and ongoing began at the start of 2024). The meditative film component of Core-Coralations not only engages with this current ecological threat, but also with the colonial history of the Reef, which Captain Cook ‘discovered’ in 1770 when a coral outcrop pierced a hole in his ship, HMS Endeavour. In turn, the largest sculpture in the project, Death Assemblage (2022), a massive flat, billboard-like work constructed out of coral, aragonite, mineral powder and resin, is part-monument, part-barrier, and acts as both an elegy to the coral death toll and an indictment of Australia’s dismal and inactive approach to climate action. When making the sculpture, Mangan mixed bioluminescent ink with the coral bones and aragonite, and then layered this on the front side of the piece. In the gallery, the finished work is intermittently bathed in ultraviolet light, with the activated pigment exposing the coral skeletons embedded in its composite surface. This pulsing glow mimics the fluorescence response deployed by corals as a protective mechanism during the bleaching process.

Core-Coralations is one of Mangan’s most profoundly affective works, and he’s conscious of the fact that it’s the emotional response often elicited by mass bleaching events that continues to draw both himself and his audiences to the project. “I don’t think it’s just because of [the coral’s] beauty,” he says, during a video call. “It’s the fact that it’s alive, that it’s an animal and it’s a mineral all at once. There’s a crossover, a blurriness, that happens.” And in other works, such ambivalent blurriness takes on a variety of forms.

After gaining independence in 1968, the Republic of Nauru, a Micronesian island-state, experienced a sudden moment of wealth, having sold the rights to its phosphate reserves to Western interests. A large portion of the profits was invested in international real-estate, including Nauru House, a highrise building in Melbourne, which featured two coral limestone pinnacles shipped from Nauru in its forecourt.

By the early 2000s, Nauru’s deposits had been exhausted and decades of strip-mining had caused widespread environmental damage. Facing bankruptcy, the world’s smallest republic was forced to sell off many of its assets, including Nauru House. At the same time, the Australian government began implementing its brutal and contentious ‘Pacific Solution’, transporting asylum seekers to offshore detention centres in Nauru and other island nations. In 2003, President Bernard Dowiyogo, just before being hospitalised in Washington, DC, confided to a journalist that he had a plan to turn around Nauru’s economy: he wished to use the island’s remaining coral limestone to construct ancient coral coffee tables, which could then be sold to the US market. Dowiyogo died a short time later, before his idea could reach fruition.

In one of his earliest bodies of work, Nauru – Notes from a Cretaceous World (2009–10), Mangan charts this complex sociopolitical and ecological history via sculpture, archival images and objects, and video. His project enters the narrative by attempting, symbolically, to complete the former president’s proposition. Dowiyogo’s Ancient Coral Coffee Table (2009–10) is made from a sliced section of coral limestone supported by limestone legs (Mangan sourced the material from the pinnacles that once graced Nauru House). With its chalky-white tone and fossilised coral, Mangan’s table renders Dowiyogo’s scheme in all its absurdity, imbuing the geological material with Nauru’s tale of economic and environmental collapse.

Coral-Coralations and an excised selection of works from Nauru – Notes from a Cretaceous World both appear in A World Undone, Mangan’s first retrospective, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), Sydney, which showcases eight expanded sculptures. With a practice spanning two decades, Mangan’s work can be defined by what he describes as a longstanding interest in ‘material storytelling’ – in the way that physical objects allow us to comprehend more abstract political, economic and social systems, and then, in turn, how these systems engage with, or transform, the physical world.

“I don’t think in a linear way,” Mangan tells me. “I think in a way that sort of brings things together.” That is, rather than conceiving of an event in chronological or cause-and-effect sequences, Mangan is more interested in how different materials or forces surrounding the event might compound or interact with one another. Indeed, it is his action of disassembling or reassembling materials – be they a rock sample, an archival print, a newsreel or a photocopier – that then enables us to understand the world anew. Part of it is “an attempt to think about how things might be other than they are”, says Mangan. “How we might take a different path, or open things up, or reconfigure them in a different way.”

Such an approach has led Mangan to a sustained focus on energy: its extraction, production and depletion; how it might be divided, compressed or redistributed. Progress in Action (2013), also currently on view, considers events linked to the Panguna copper-mine established by a subsidiary of the Australian company Rio Tinto in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, which led to a brutal civil war from 1988 to 1998. The Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA), which mounted the opposition to the mine and found itself cut off from fuel and resources, turned to coconuts as a source for biofuel. Mangan’s installation, paying homage to this act of eco-resistance, includes a provisional coconut-oil refinery and modified diesel-generator. (While it was originally presented as a working model powering a projector, Mangan decided that recent iterations would only show the work in displayed form, given the unsustainability of the refining process.) Alongside the generator, a video montage splices together a range of footage from Shell Corporation, newsreels, Australian government film units and current-affairs programmes in a rapid succession. With its emphasis on jump-cuts and repetition, the film reiterates Mangan’s materialist approach to storytelling.

For Ancient Lights (2015), which references the 1663 British doctrine safeguarding the ‘right to light’ from already-existing windows in the face of urban redevelopment and expansion, Mangan has created an energy system within the gallery: the work converts sunlight (via solar panels installed on the gallery’s roof) into energy, which is then converted back into light through two digital film projectors. One projector then displays a series of images linked to the sun, such as tree rings from a laboratory in Arizona, or a 24-hour solar storage plant in Spain. The other shows a video of a revolving Mexican ten-peso coin that depicts the Aztec sun god Tonatiuh, the footage edited so that the coin spins indefinitely. Here the turning of the coin symbolises not only economic value, a never-ending shift between surplus and expense, but also the sun’s energy in motion.

For Mangan, each of an installation’s components, be it an image, a generator, a power cord or coral rubble, can combine with others to form what he describes as a “zone” – an open-ended system built from the aggregation of parts. Limits to Growth (2016–21), an iterative work that Mangan has repeatedly revised and extended, investigates the connections between two seemingly disparate forms of currency: Rai stones, an ancient money from the Pacific island of Yap, and bitcoin. Here Mangan is considering whether Rai – large limestone discs with a carved hole in their centre – can be seen as anticipating digital currency. In the case of Rai, an oral ledger validated ownership, so a stone often did not have to be physically moved (which, due to their sometimes-huge scale, would have been difficult at best) to be traded or owned – a method that aligns with contemporary bitcoin operations.

Alongside this, Mangan is also engaging with the ostensibly immaterial bitcoin’s hidden material impact: the reserves it draws from energy infrastructure, and the environmental cost required to sustain cryptocurrency transactions. In the work’s first iteration, Mangan set up a bitcoin mining rig, the profits from which were used to fund the production of photographs of Rai stones. Each of these images then had an indexical relationship to the value created and energy expended via the mining. In the most recent version, Limits to Growth – Part 3 (Letter to Rai) (2020–21), Mangan has mined the artwork itself. Extracted aluminium from the obsolete computers used to set up the bitcoin mine is turned into ingots, and 149 shredded surplus photographs are transformed into a giant papier-mâché Rai stone. (The process of making these works is also documented and presented via a video in the space.)

The Indian writer Amitav Ghosh has argued that the failure to address climate change is a failure of imagination. Too often Western-centric narratives view nature as inert and thus easily relegated to the background, which in turn leads to a ‘great derangement’ (as Ghosh’s 2016 book on climate change is titled) – the belief held by many humans that they exist outside of nature, even as we remain wholly dependent on it. For Ghosh, new narrative forms must emerge that push against such a dangerous belief. What is required, then, is exactly the kind of material storytelling that is so central to Mangan’s practice: a refusal to separate human agents, systems and processes, a desire to aggregate and chart energetic forces, and a reminder that systems and worlds can be undone, and remade.

Nicholas Mangan: A World Undone is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), Sydney, through 30 June

Naomi Riddle is a writer and editor based in Sydney