Everyday stories in the face of world-changing events kept me sane

There seemed to be a common consensus (well, on my social-media streams, through which I initially did far too much doom-scrolling) that, during the white heat of the first COVID-19 lockdown, people were too anxious to concentrate on reading books or any other similarly ‘productive’ activity. I worried (because social media is 99-percent worrying about saying the wrong thing) that I might appear insensitive if I noted the government-mandated opportunity not to go out had proved a golden opportunity for me to stay in and delve into the ever-accumulating ‘to read’ pile. Anyway, now, with some distance, I can admit I found it pretty productive (albeit only after I resolved only to look at the news once per day.)

Nor did my reading veer into escapism. In fact, I ended up turning heavily to history or novels set during wartime, finding perverse parallels between the truly global event of the pandemic, with its myriad local and personal consequences, and those authors who successfully hone in on intimate stories as a vehicle for telling much larger narratives of conflicts past and present. Some of this reading naturally does not fall neatly into an end-of-year book roundup, however. For example, I read Tim Judah’s 2015 In Wartime: Stories from Ukraine (Allen Lane, £9.99, softcover), which unfolds the history of Europe’s largest country through personal reportage from his time as foreign correspondent and found that it was full of details pertaining to the lived mundanity of generation-defining events that chimed with the strange boredom, for the lucky and privileged (such as myself), that the pandemic served up.

Sticking within that broad geography, Anne Applebaum’s fervent neoliberalism ruined her 2012 Iron Curtain: Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944–1956 (Penguin, £14.99, softcover) for me, her personal politics intruding on the narrative, despite the elegant and epic prose style. I mention it because it stood in stark contrast – politically – to Vincent Bevins’s The Jakarta Method (PublicAffairs, $17.99, hardcover), published last year, which tells how the CIA-backed coup of 1965–66 (and the atrocities that followed) proved a blueprint for subsequent American-led covert operations around the world. Where Applebaum is at pains to present communism as the driving force behind much of the evils of the twentieth century, by pulling at strands in the archives and through witness statements, Bevins demonstrates that an equivalent evil lay hidden in the west (for example, an estimated one million were killed in Indonesia, with American approval).

More even-handed is Will Grant’s new book Populista: The Rise of Latin America’s 21st Century Strongman (Head of Zeus, £25, hardcover). In it, the BBC’s Mexico, Central America and Cuba correspondent offers chapter-by-chapter profiles of some of the southern continent’s iconic leaders, from Brazil’s Lula to Ecuador’s Rafael Correa, mixing the personal and political to chart the so-called ‘pink tide’ that brought various left-wing governments to power in the region during the 2000s and 2010s (Brazil’s current far-right president Jair Bolsonaro’s appearance on the cover is a visual misnomer as he features only tangentially). While the book fails to offer a concrete definition of ‘populism’ (other than a loose rejection of neoliberalism and entrenched inequality, one that doesn’t hold water outside the region), Grant expertly traces how the actions and views of his subjects played out on ordinary lives, for better or worse, from women like Jostina Chuquijuanca de Soria, who praises Evo Morales’s use of Bolivia’s oil money to fund a health centre in her remote Andean village, to those starving under what Venezuelans have grimly termed the ‘Maduro diet’ of inflation and food shortages under the country’s current president.

Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting (Faber & Faber, £20, hardcover), a new biography of five female writers who all lived (some concurrently) in the same London square at some point in the early twentieth century, ends with an account of how her five protagonists – Hilda Doolittle, Dorothy L. Sayers, Jane Ellen Harrison and Virginia Woolf – negotiate the advent of the Second World War. From Wade’s point of view, formed via studies of personal letters and archives, the impact of this global event is at first psychological, as she traces how the stresses of war played out in minds and emotions. ‘The war had affected her subconscious in a disconcerting and pernicious way’, she writes of Woolf. ‘Forcing her to think communally rather than as an individual.’ Wade goes on to quote Woolf herself: “We think of weather now as it affects invasions, as it affects raids, not as weather that we like or dislike.” The 350 pages of Square Haunting are full of similar quiet revelations, of history rendered personal, as she steers her characters stories, each told in a dedicated chapter, as their lives invariably overlap socially and professionally (as well as geographically) and through this interweaving tell the larger tale of pioneering women pushing through barbarically sexist restrictions on study and work, bad pay and bad men, to achieve remarkable success. With the exception of Woolf, and despite their enviable bodies of work, their achievements are barely remembered today however. Wade’s book is a reminder that the battle for gender equality is far from over.

By autumn my reading was consumed with my own ongoing research project, and all energy was diverted to finding small gaps in successive lockdowns to get into libraries and newspaper archives. If nothing else, this year served an important reminder of the importance of libraries, even though that importance was evidenced by their absence. Right on cue I got my hands on a copy of Edmund De Waal’s Library of Exile (The British Museum, hardcover, £10). Published to coincide with a curtailed show at the British Museum, the catalogue proved a partial substitute for the actual installation. The artist (whose elegiac 2010 family history, The Hare with Amber Eyes, is an enduring point of reference for me) has compiled a vast library of books, all written by authors in exile, from Ovid’s Tristia (8) to Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came To Tea (1968). These were to be shown in London before finding a permanent home at the reconstructed University of Mosul library. ‘Banned books become burned books’, de Waal writes in his text. ‘This is trial by fire, the testing of what should survive and what be destroyed forms a terrible skein across the centuries.’

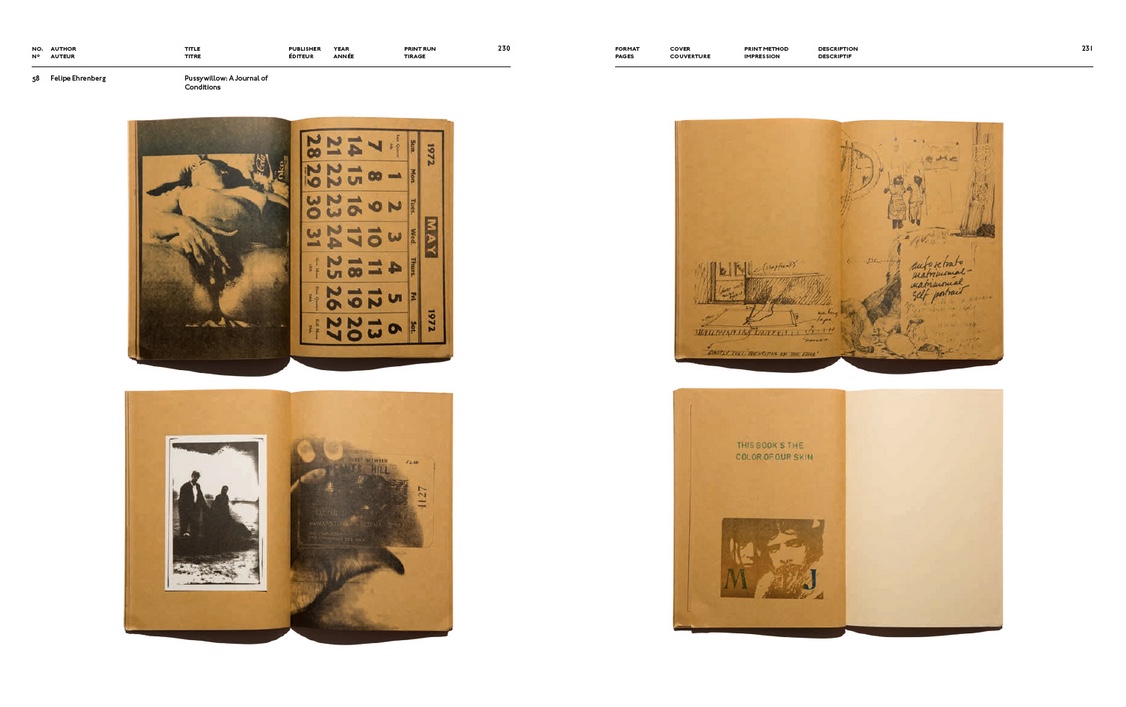

The Brazilian artist Hudinilson Jr fought repression and censorship too, making a body of work during his country’s dictatorship years that proves a continued influence in the politicised queering of the body evident in so much Brazilian art today. Hudinilson Jr’s work, surveyed at São Paulo’s Pinacoteca, and in the accompanying publication (Pinacoteca, R$60, hardcover) published this year, lends itself to book form, given that the artist’s visual activism was invariably played out primarily through notebooks collaged with magazine clippings and Xerox photocopies of his own naked body. DIY publishing, as a radical act, was also the preserve of the Beau Geste Press, set up by two Mexican émigrés, the married artists Felipe Ehrenberg and Martha Hellion (escaping American-backed persecution), and art historian David Mayor in rural England in 1971. The new catalogue raisonné (CAPC/Bom Dia Boa Tarde Boa Noite, softcover, €39), edited by Alice Motard, stemming from a recent retrospective she curated at the CAPC in Bordeaux, is a rich treat, full of texts, drawings, poems and games from the trio and their collaborators, including Carolee Schneeman and Cecilia Vicuña, all underscored with the anarchic politics of Fluxus.

Art catalogues offer me temporary respite when the energy needed for a full novel or extended work of non-fiction is lacking. The same can be said for poetry too. Of the latter Faber reprinted Hope Mirrlees’s ‘lost’ modernist epic Paris: A Poem (Faber, hardcover, £9.99) and reading for it the first time was mind mending (originally published by Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1919; Mirrlees was one time partner of Jane Ellen Harrison). Set over a single day it offered a glimpse, from isolation in London, of the French metropolis, postwar, as Europe’s recovering capitals began to bustle and life slowly resumed a ‘new’ normal. Woolf called the work ‘obscure, indecent, and brilliant’ and Mirrlees’s trip through the boulevards and pavements are told in lines that weave in and out of English and French with, at points, both languages seemingly collapsing completely.

A highlight: ‘But behind the ramparts of Louvre / Freud has dredged the river and grinning horribly / Waves his garbage in a glare of electricity / Taxis, Taxis, Taxis / They moan and yell and squeak / Like a thousand tom-cats in rut.’

It’s a portrait of a society brought almost to ruin, but one in which, when pushed to the brink, allows new life to seed once more. Here’s looking to 2021 then, when cats (and humans for that matter) in the city might rut once more.