ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists and curators exhibiting in and curating the various national pavilions of the 2022 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the leadup to and during the Venice Biennale, which runs from 23 April to 27 November.

Tsherin Sherpa is representing Nepal; the pavilion is in Sant’Anna Project Space One, on the Fondamenta S. Anna between the Arsenale and Giardini.

ArtReview What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

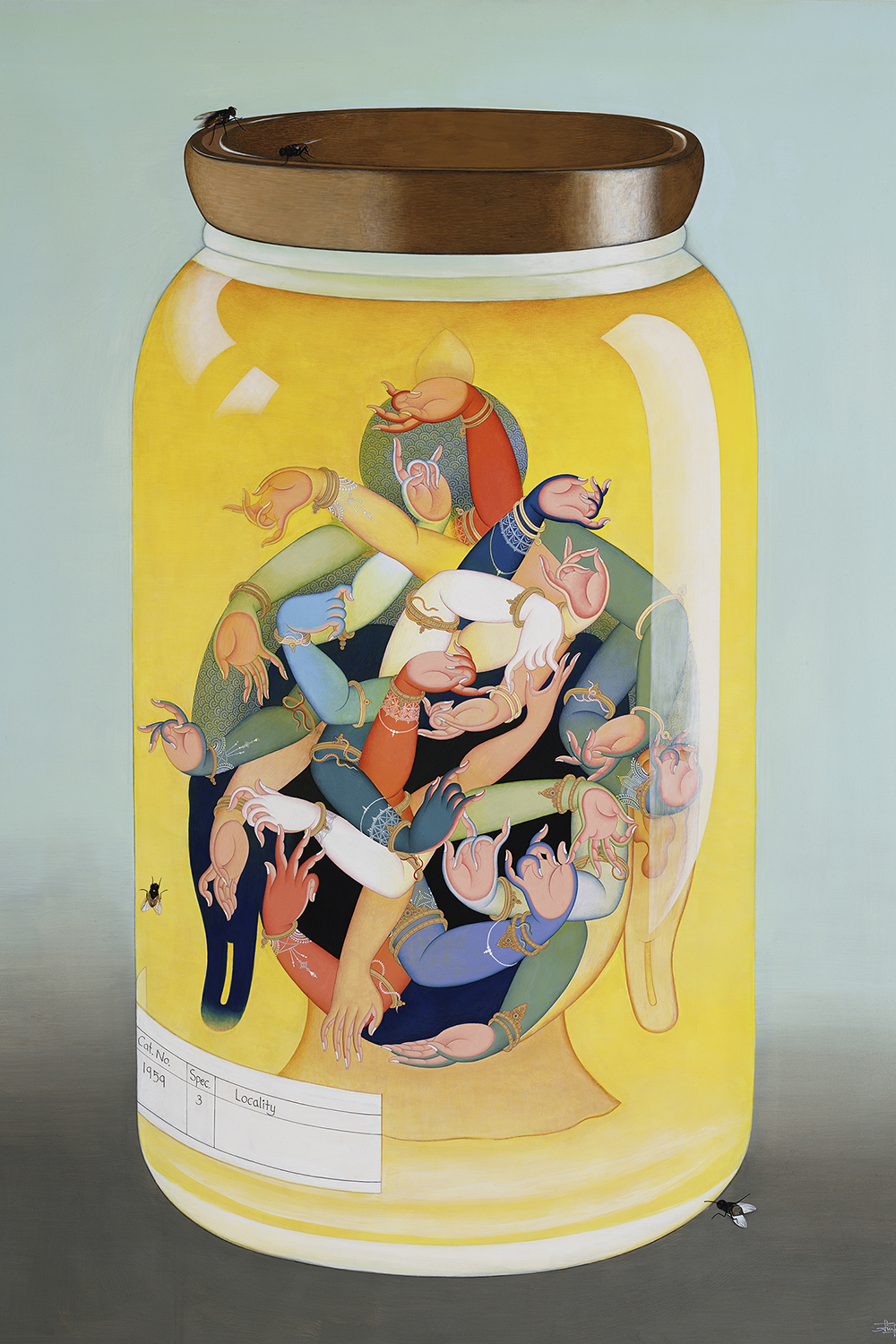

Tsherin Sherpa For the Pavilion of Nepal I will collaborate with artists across Nepal to produce a body of work that incorporates multitudes of artistic traditions, such as metal sculptures, woollen carpets, nettle textiles and paintings. International understanding of Nepali art remains plagued by a Western conceptualisation of the Himalayan region: a pervasive, romanticised vision that frames Nepal as static, pure and untouched by time and modernity, the ‘Shangri-La’ effect. The pavilion will create a space to reflect on and reevaluate these biases.

Tales of Muted Spirits – Dispersed Threads – Twisted Shangri-La, curated by Sheelasaha Rajbhandari and Hit Man Gurung, will stimulate sensorial experiences of the audience through sights, touch, smell and sounds. Oral histories, archival footage and performative traditions will be presented in a manner that implicates the intersectional and intertwined histories of the Himalayas to the rest of the world. In effect serving as a commentary on the uncertainty underpinning both the emic and etic narratives through which communities from within the region are represented and understood.

AR Why is the Venice Biennale important to you?

TS The Venice Biennale is the oldest and arguably most significant international stage for the visual arts. A pavilion at the Venice Biennale will provide artists from each participating country, including Nepal, with an invaluable international platform to showcase our work.

I hope the Nepalese pavilion will position our country to contribute to a broader narrative on contemporary art. But also the core motivation for this project is the possibility of holding up a mirror to traditional arts and artists. The project is an observation of the diminishing value of traditional Nepali arts, and an invitation to reexamine our understanding of it.

Perhaps then we may find ways of forging collective paths forward.

AR Do you think there is such a thing as national art? Or is all art universal? What is misunderstood or forgotten about your country’s art history or artistic traditions?

TS I think art is universal in the way it should connect and speak to everyone who’s experiencing it.

At the same time, art and artists have always been deeply tied to their own religions and cultures and art is often commenting on the political and social conditions where it is produced.

In this way, each nation has a different and unique voice in what we can call ‘universal’ art.

Regarding Nepali art, the main misunderstanding is how art remains plagued by the Western conceptualization of the Himalayan region I refer to above.

In my country artists were trained since childhood, learning all aspects of their practice from master artists. They were supported by the patronage of religious institutions and the rulers. Their works in turn strengthened the role of religion in society – the images of gods and goddesses, the religious stories retold through their paintings and the religious motifs in their sculptures helped pervade these ideas in the collective psyche. These works reached the ordinary citizen through wall paintings, portable painted scrolls, manuscripts, local shrines, residential architecture and so on. In fact, these artforms are the bridges that have ensured the passing on of the knowledge of these cultures in the veil of tradition.

Over the course of the past five decades Nepal has opened up to international markets. Unfortunately, the increasing demand for traditional Nepali art by foreign buyers has created a new market for artists. But the lack of support or supervision from the government and religious institutions has forced a cheap commodification of this art.

AR Which other artists from your country have influenced or inspired you?

TS If we are speaking specifically of artists from my country, the most influential to me will have been my father, Master Urgen Dorje. It was under his tutelage that I trained to be a traditional thangka painter. There were hardly any museums or art galleries in Nepal when I was growing up, so there was no discourse between traditional and contemporary/modernist artists in Nepal. My exposure to contemporary art really only came after I moved to America in 1998.

This is why the pavilion is so important for Nepal: we are trying to create a platform where artists from different traditions can come together, have conversations and engage with one another.

AR How does having a pavilion in Venice make a difference to the art scene in your country?

TS Unless we are able to reestablish our traditional arts as the reservoirs of our collective history and knowledge, we are doomed to lose a valuable part of our identity.

The Nepalese pavilion at the Venice Biennale is my attempt to find ways in which the traditional arts and artists could get their due respect and support.

My belief – and hope – is to raise the profile of Nepal as one of the most vibrant countries for the production, promotion and presentation of contemporary art.

AR If you’ve been to the biennale before, what’s your earliest or best memory from Venice?

TS I attended the 58th International Art Exhibition, the edition curated by Ralph Rugoff, May You Live in Interesting Times.

I was captured by the presence of so many different countries and voices, including a few that were exhibiting for the very first time, like Ghana and Pakistan. In that very moment I started thinking about the role of art and the importance of giving my own country a voice in such an international platform.

AR What else are you looking forward to seeing?

TS I was really excited to see that this will be the first time the majority of the artists selected for the Biennale’s curated exhibition are non-male and female-identifying. I look forward to seeing Cecilia Alemani’s curated exhibition and any pavilion or collateral event that gives voice to those who have historically been silenced.