Two Brazilian artists channel the fears and anxieties of their times

That Ivan Serpa was mentor to the likes of Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape has determined which of the artist’s own works are best remembered. In 1954 the Brazilian founded Grupo Frente, the pioneering school of Latin American Concretism of which those more famous names were members. Some of Serpa’s paintings of geometric abstraction are included in an extensive survey of over 200 of his works at CCBB São Paulo, but the real service The Expression of Concrete provides is in, despite the title, showing how much more varied and restless an artist Serpa was.

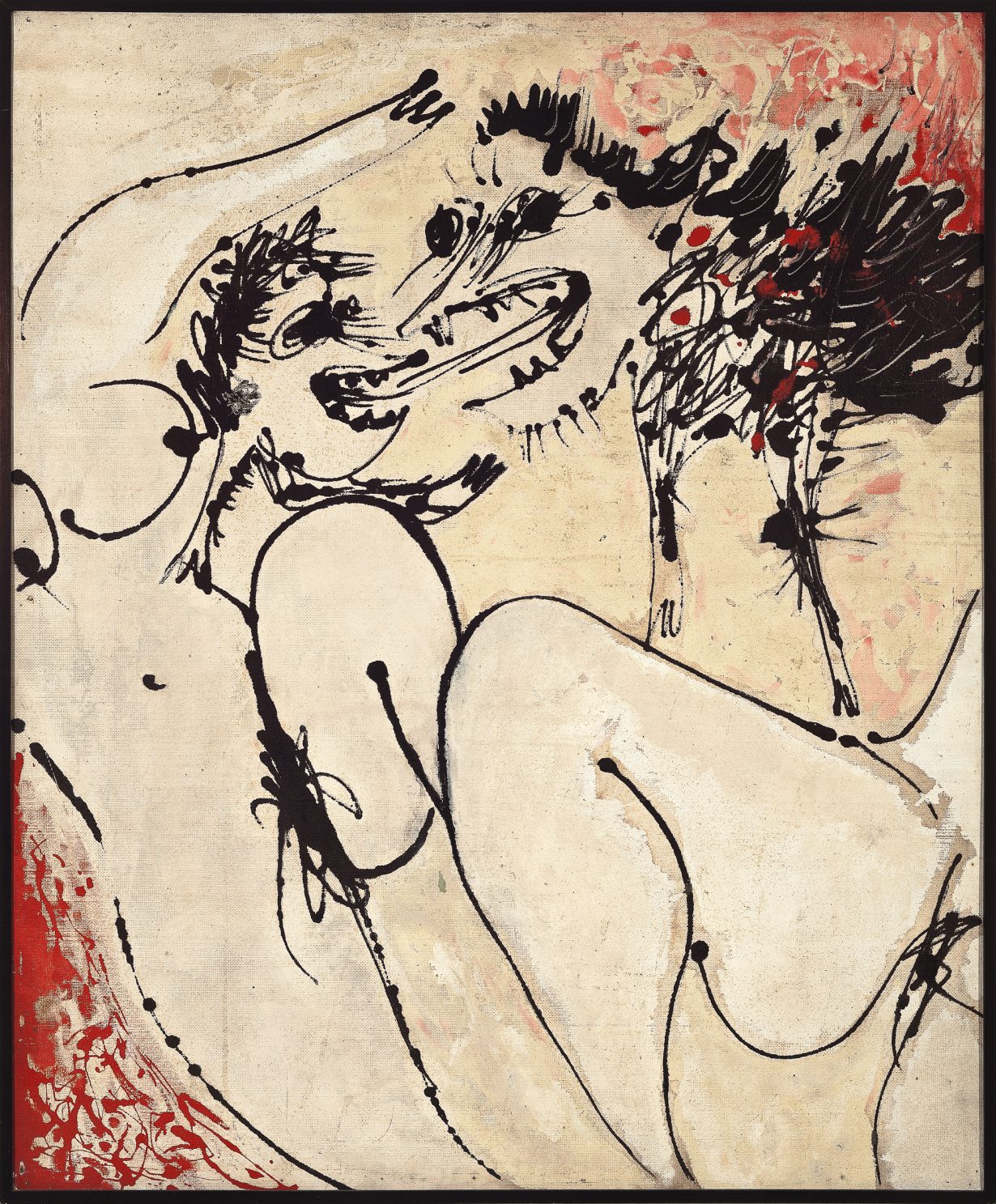

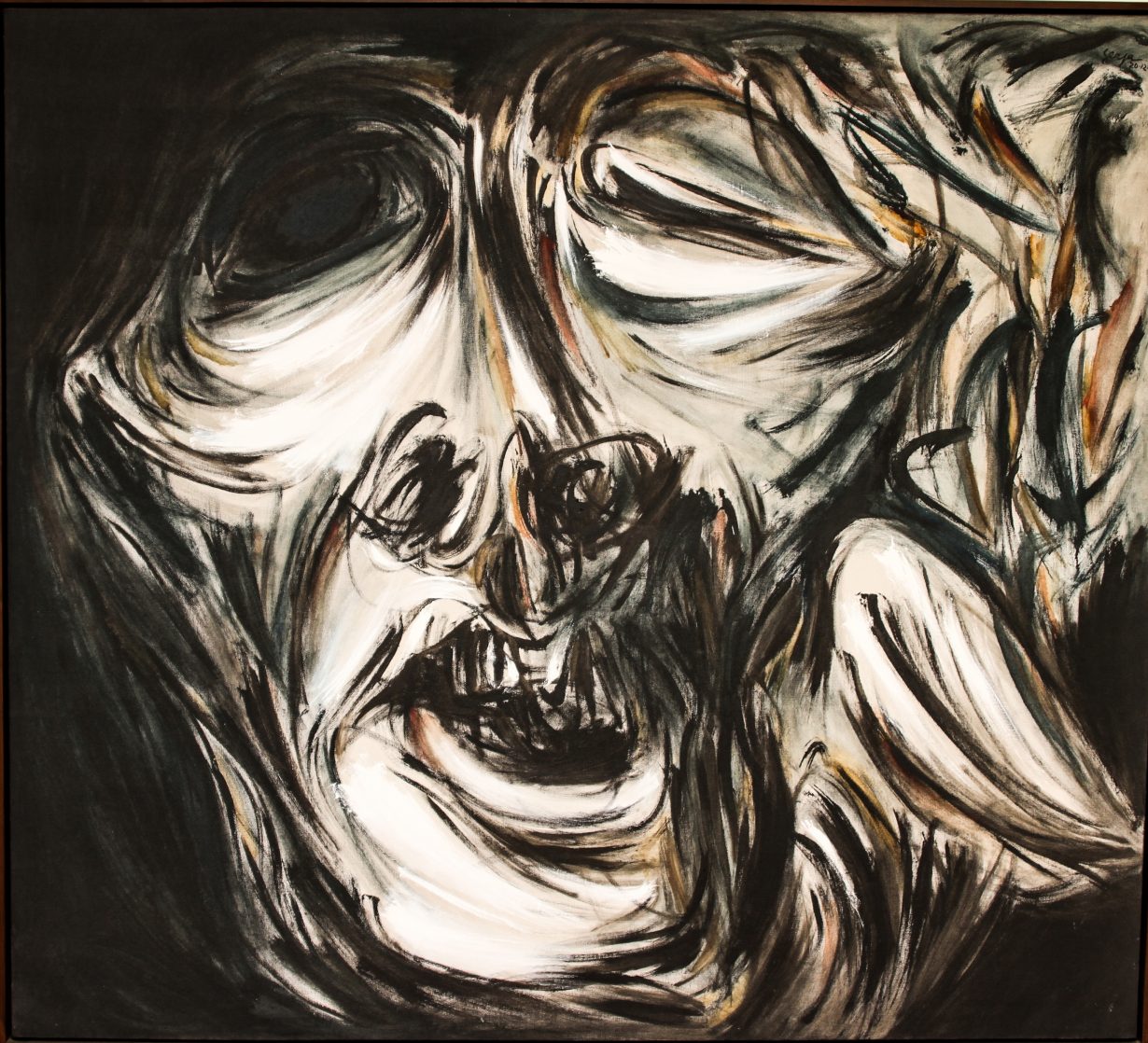

During the late 1950s he won a travel bursary, setting off to Europe to immerse himself in the prevailing art trends, a trip that had a profound effect on his work. On his return to Brazil he put aside paintings such as Faixas em ritmo resultante (Resulting rhythm tracks, 1956) – a red-and-blue geometric oil-on-wood composition, in which the two blocks of colour are divided by what appear to be elongated musical crotchets – and instead embraced a style of monstrous figuration. An untitled 1965 oil on canvas from the Women and Animals series depicts a woman, naked, being consumed by the writhing bodies of two, perhaps three, otherworldly creatures. The composition is a delirium of messily composed black lines, the darkness picked out by splatterings of red. In another painting, made the same year, the head of one of these demonic animals seems to protrude from the torso of the same naked woman (her own head out of frame). One can make the assumption that among the artists Serpa studied on his European tour were Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst and Francis Bacon (though Serpa would have been aware of Picasso’s contortions of the female form – ‘machines for suffering’, as the Spaniard horrifically called women – as early, at least, as the first Bienal de São Paulo, in 1951), the Brazilian artist taking the patriarchal violence of their Jungian dramas and transplanting them to a country entering its darkest moment. The violence and transgression of the Women and Animals paintings, and the related Animals series (1962), I’d argue, evoke the social and political nightmare of Brazil’s dictatorship years.

In an untitled Animals work, multiple eyes of numerous blobby fiends painted in orange, red and blue likewise recall the swirling anarchy of Picasso’s antiwar Guernica (1937) as they gnash their teeth against each other. Another of Serpa’s untitled works, from a year later, shows two further monsters staring at each other, set against a swirling blue background, both savage looking, both with pendulous breasts, which might conceivably also serve as wings. In a third oil on canvas, a green biped critter seems to eat the ass of a white four-legged opponent. While they owe something to European art’s avant-garde, including the COBRA artists, they are not derivative, incorporating a uniquely local sense of the monstrous – tropical, feverish – evident in Brazil since the work of painter Tarsila do Amaral and poet Oswald de Andrade three decades earlier. Of course, we take from art what we need for the moment, and it is perhaps inevitable that in a time stalked by the spectre of a virus and all the anxiety that produces, it is these horror scenes that I’m drawn to over the earlier cool experiments in colour and form (though Serpa would return to geometric abstraction in the 1970s).

Monsters abound too in Yuli Yamagata’s Insônia (Insomnia), a solo show at Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, São Paulo, of 18 wall-, plinth- and floor-based sculptures. The artist, born in 1989, brings a similar level of underlying anxiety to these predominantly textile works as that found in Serpa’s art. In an exhibition statement Yamagata references both director David Lynch and how the line between dreams and reality is blurred in Japanese manga; indeed, a work such as Cyborg Nascendo (all works 2021), a fabric collage stretched over a frame in which a figure lies, the palms of their feet facing the viewer, under a tie-dye blue sky, raises all sorts of questions. Is the person dead? Are they a robot? Are they dreaming? Is this a nightmare? We don’t get any answers. Yamagata’s show is full of motifs that lead you to search for their significance yet that ultimately resist explanation – a giant, padded fabric octopus lunges out from behind a dark velvet background in the wall-work Polvo Nadando (Swimming Octopus); a plinth-based sculpture, Pudim (Pudding), features a cob of corn hanging from a rod mounted on a lump of green resin.

What prevails in both Serpa and Yamagata’s exhibitions is a gnawing uncertainty reflective of the weird times in which the work was made. Their strange visions, decades apart, chart how political repression or pandemics are psychological events as much as anything else: the trauma and neurosis of the external world invading the subconscious, crawling into the imagination of both artist and viewer alike.

Ivan Serpa, The Expression of Concrete, was on view at CCBB São Paulo, 3 February – 12 April

Yuli Yamagata, Imsonia, was on view at Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, São Paulo, 24 April – 29 May