The current Documenta 14, headed by curator Adam Szymczyk, is titled ‘Learning from Athens’. The Kassel-based quinquennial’s extension to the Greek capital opened in April, while the Kassel mainstay opens in June. It would be fair to say that Szymcyzk’s Athens experiment hasn’t been met with universal praise – beyond the professional artworlder complaints of a sprawling show that’s hard to navigate, bare-bones information accompanying works and little notice of who or what was in the show until days before, the rationale for the show’s presence in Athens has itself been the object of much of the confusion and misgiving. After former finance minister Yanis Varoufakis’s early snipe, back in 2015, at the show’s ‘crisis tourism’, the impression that the relationship between Kassel and Athens mirrored the relationship between a creditor Germany and a debtor Greece has been hard to shift. That suspicion of a ‘colonial’ relationship hasn’t been helped by the reportedly aloof and secretive attitude of the organising team when dealing with members of the city’s art scene.

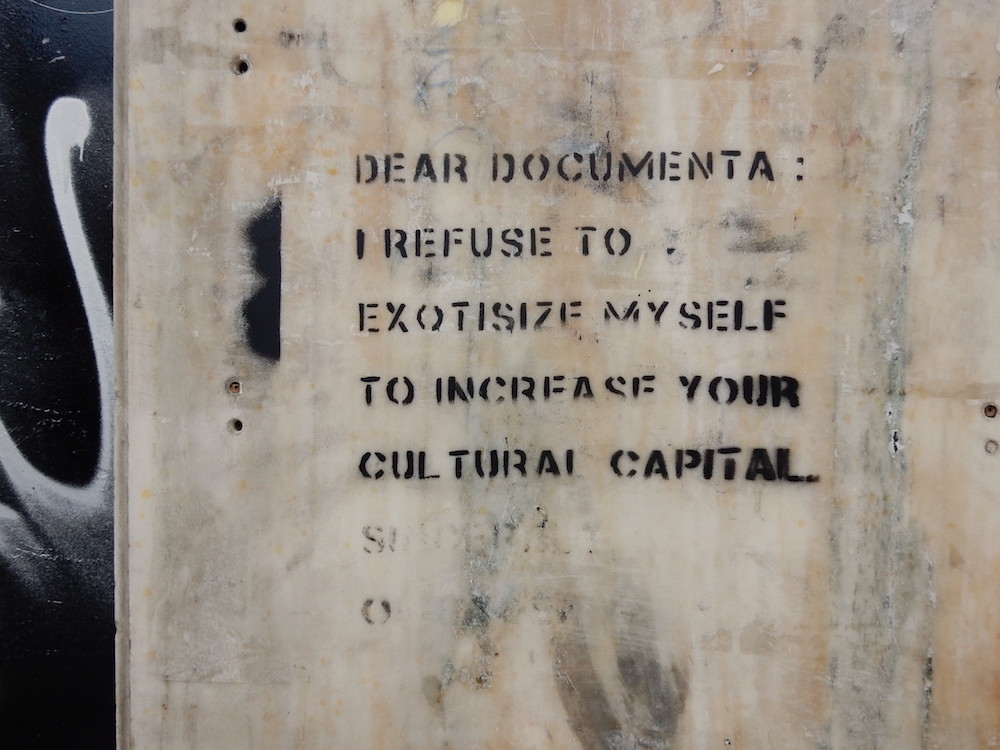

But perhaps that impression of a ‘colonial’ attitude isn’t just the unfortunate symbolic fall-out of a wealthy Euro-north-based art event of deigning to rock up in solidarity with the impoverished peoples of the Euro-south. It’s more straightforwardly down to the nature of any big art event headed by a star curator. Biennials and quinquennials aren’t democracies, they’re benign dictatorships; whatever Szymczyk’s intention in pushing the issue of art’s pretensions to social effect to the fore by displacing Documenta from its enclave in boring, comfortable Kassel, and regardless of Documenta’s rhetoric concerning a world riven by political fragmentation, migration crises and failure of democracy, Documenta remains just another curator-authored megashow.

And while its rubric ‘learning from Athens’ sounds equitable and collaborative, it inevitably runs into the limits of the agendas its curators want to pursue, its own eccentric mix of political and theoretical tendencies currently occupying the artworld’s curatorial elites; tendencies that, in Documenta 14’s case, are largely indifferent to the conditions that its Greek hosts currently endure.

Szymczyk’s Documenta is brim-full of political opinions: so, for example, the agenda for forthcoming programme of talks, organised by trans activist Paul B. Preciado, asserts apocalyptically that ‘the planet is going through a process of “counter-reform” that seeks to reinstall white-masculine supremacy and to undo the democratic achievements that the workers’ movements, the anti-colonial, indigenous, ecologist, feminist, sexual liberation, and anti-psychiatric movements have struggled to grant during the last two centuries’.

The particular elephant in the room of Documenta should be evidence enough that ‘large international exhibitions’ are not good places to pretend to do politics

These are the recognisable currencies of discourse that preoccupy identitarian radicals in and around the artworld; intersectionalist and minoritarian, they have little to say to the majority of Greeks who are faced with the usurpation of their democracy by outside forces. But representative democracy seems to little interest Documenta’s programmers – in an article titled ‘The Stateless Exhibition’ Preciado writes in vague and generalising terms about ‘a war of the ruling classes against the world population, a war of global capitalism against life, a war of nations and ideologies against bodies and immense minorities.’ He goes on, with cool disdain, to state that ‘the economic and political sacrifices to which Greece has been subject since 2008 are simply the beginning of a broader process of the destitution of democracy extending throughout Europe.’ Preciado quickly turns to blame the ‘ultra-conservative turns in Hungary, Poland, Ukraine, Brazil, Turkey, the coming to power of Trump, Brexit…’

This is strange, to say the least, since the one force which has destituted democracy in Greece is, after all, the EU – an institution with its own severe democratic deficit, desperate to hold on to its systems of power even while citizens across the continent regularly express their antipathy towards the EU ‘project’. Yet in all the coverage of Documenta, and its own prolific pronouncements and publication, almost nothing has been said of the Union, that vehicle defending the interests of the ‘ruling elite’ against those of the Greek people.

That particular elephant in the room of Documenta should be evidence enough that ‘large international exhibitions’ are not good places to pretend to do politics, since the autocracy of such institutions is by definition incapable of accommodating the democratic participation of local art scenes artists or publics, of truly representing and experiences of those they claim to engage with. If Documenta in Athens has generated resentment and confusion, it might be precisely because the one single issue most affecting Athens today is the one thing about which Documenta refuses to speak.

From the May 2017 issue of ArtReview