In his psychedelic and gleefully unhinged films, the director has long transcended both social conventions and the limits of animation

Japanese director Masaaki Yuasa has long been fascinated with processes of transformation: the transformation of audience expectations, of artistic conventions and of people into their truest selves. Take a key moment in his debut anime feature, Mind Game (2004), featuring a bout of delirious lovemaking, during which a character sprouts wings, the abdomen of an insect and pulsating spikes. As both characters become an entangled mass of kaleidoscopic paint, their union is spliced with images of melting butter, live-action footage of waves lapping at a beach and a train careening off a cliff – all set to a summery bossa nova track.

A deeply idiosyncratic figure in animation, Yuasa worked under legendary animators like Isao Takahata (Grave of the Fireflies, 1988, My Neighbours the Yamadas, 1999) before cementing himself as an auteur in his own right. Known for a trademark psychedelic style that transgresses the traditional bounds of anime (typically 2D and drawn in a single aesthetic style), Yuasa has found international acclaim for series such as The Tatami Galaxy (2010) and Devilman Crybaby (2018), while also helming a guest episode for US cartoon sensation Adventure Time (2010–). In May Yuasa released his latest feature, Inu-Oh, to the public, following a competition screening at the Venice International Film Festival last year.

When Yuasa first appeared on the anime scene, with Mind Game, home audiences didn’t know what to make of him. Although he had previously worked as an animator and storyboard artist on popular series such as Chibi Maruko-chan (1990–92) and Crayon Shin-chan (1992–), these offered little introduction to his personal vision: unbridled, crass, joltingly experimental, in stark contrast to formulaic mainstream anime. The film operated on a gleeful irreverence towards traditional frontiers, defined by its own rollicking sense of dream logic.

Mind Game follows a slacker named Nishi and his hopeless devotion to his now-engaged childhood crush, Myon. When Myon is pursued by a pair of Yakuza gangsters, Nishi attempts to rescue her: immediately he gets shot through the anus and dies. But Nishi’s journey barrels on, as he tumbles through limbo, rebirth and a high-speed car chase. Nishi and Myon are eventually swallowed by a giant whale, trapped for 30 years inside its belly. In this private, surreal space, they can finally explore the dreams they gave up on – art, dance, swimming – and rediscover their love for one another. Yuasa’s unorthodox plotting and fondness for mind-bending images set him apart from other Japanese anime directors; but Mind Game bombed at the box office.

Yuasa’s eclectic taste is reflected in his unusual, freeform approach to animation: his penchant for fragments that speak both to the subconscious and to the sublime can be traced to the breadth of transnational influences that the director evokes. These range from pop songs and commercials to the movement of grass; from the surrealism of Salvador Dalí and the virtuoso over-exaggeration of Tex Avery to The Beatles’s 1968 animated film, Yellow Submarine. In an interview with Nick Narigon for Tokyo Weekender, Yuasa explains his fixation on a fight sequence in Disney’s 1981 film The Fox and the Hound, where the titular fox fights with a hulking black bear, their bodies at points in the animation seeming to swirl and blend: ‘I found it interesting that while those [abstract images] were not recognizable, they were still giving impact, and influencing the viewer’.

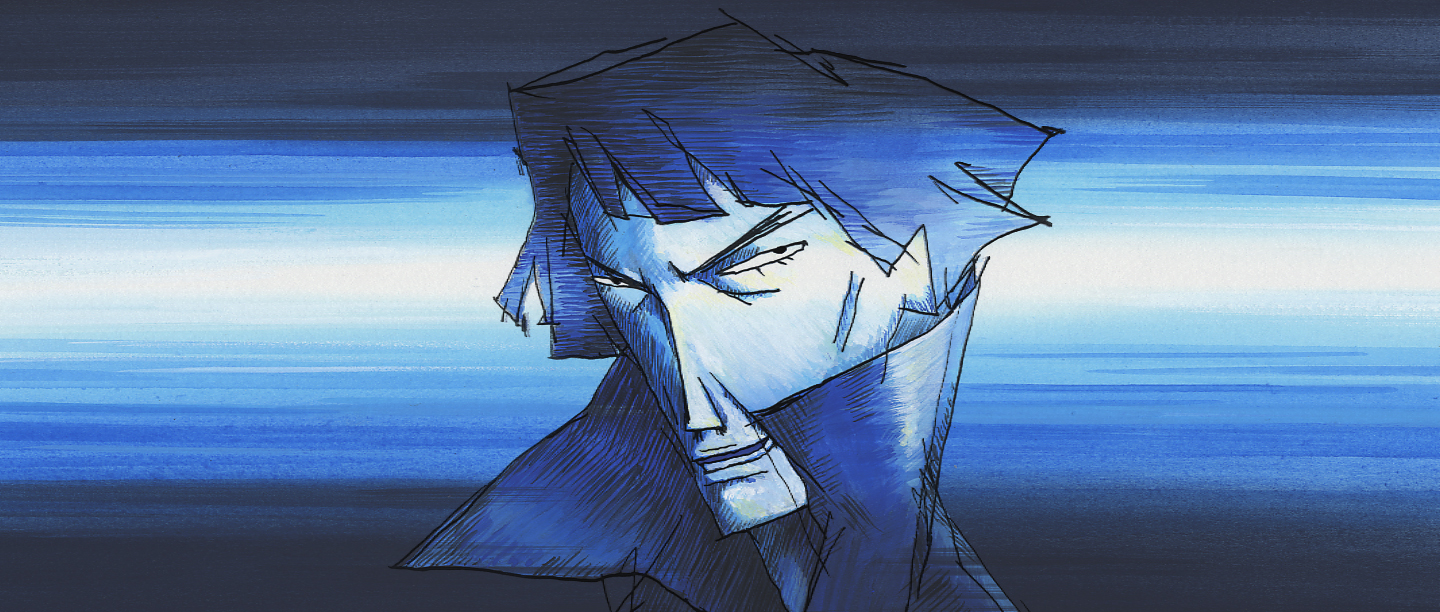

Mind Game utilises a jarring hybrid of disparate styles that, at the time, was highly unusual in feature anime films. Sequences often shift between 2D and 3D, rotoscoping, watercolour paintings and papercraft. When his characters experience a fit of pique, photographs of real-life actors are dramatically superimposed onto their faces. His series Ping Pong the Animation (2014), featuring scratchy linework, Flash animation and disorientating uses of perspective, redefined the sports-anime genre – a standout scene involves a player ballooning into a giant, staggering over his opponent. Here, Yuasa’s characters are rendered in a minimalist, jelly-limbed style, optimised for fluidity; their expressions are often warped and deliberately grotesque, opposing the pristine beauty of popular anime design.

While this frenetic expressionism initially alienated audiences, Mind Game quickly gained a cult following: in Japan it won the grand prize for animation at the Japan Media Arts Festival in 2004 (over Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle, which was on the award’s shortlist), but it found its greatest success in Canada the following year, winning three jury awards at the Fantasia festival, and receiving praise from acclaimed director Satoshi Kon (Paprika, 2006). Struggling to find producers after Mind Game’s commercial failure, Yuasa and his creative partner Eunyoung Choi managed to finance their feature film Kick-Heart (2013) through Kickstarter crowdfunding. The success of Kick- Heart allowed Yuasa and Choi to establish an anime studio (Science SARU), which produced the family-friendly fantasy Lu Over the Wall (2017). For the latter, Yuasa earned the coveted Cristal Award at France’s Annecy International Animated Film Festival, becoming the first Japanese director other than Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki to

win. And despite his works consistently being described as wilfully

niche, Yuasa has often expressed a desire to create sweeping, universal

experiences, his sensory messages speaking to the common pleasures of existence: Mind Game is essentially about a young man who is so eager to experience artistic and romantic fulfilment that he defies death – resurrected after a godly entity is impressed by his sheer will to live; Science SARU’s 2020 anime Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken! depicts the budding joy and boundless imaginations of aspiring teen animators; even in Yuasa’s hyper-violent 2018 Netflix adaptation of Devilman Crybaby – which has elements of bleak nihilism – the compassion of the main character manages to move Lucifer himself.

‘I want to depict freedom,’ Yuasa told Tokyo Weekender shortly after Devilman Crybaby was released. It’s the ethos of both his visual approach and storytelling. He is consistently interested in the stories of awkward adolescents, outsiders and the marginalised – people who reach for freedom and self-expression even as totalitarianism, ableism and gendered and sexual norms threaten to crush them. Inu-Oh is no exception.

On its surface, Inu-Oh is Yuasa’s most accessible work to date – a historical drama inspired by The Tale of the Heike, an epic dating from the early 1300s that recounts the legendary war between the Genji and the Heike clans, which resulted in Genji rule over Japan. Despite having the sweeping scope and lavish detail that we’ve come to expect of a period drama – both in anime and live-action films – Yuasa’s focus remains unique and intimate: the film follows the innovation of Noh theatre in the transitional period of the fourteenth century, told through the friendship between two boys with disabilities. It’s a love letter to queerness and transgressive artists, telling a Japanese folktale through the glittering, rock-opera sensibility of Todd Haynes’s Velvet Goldmine (1998).

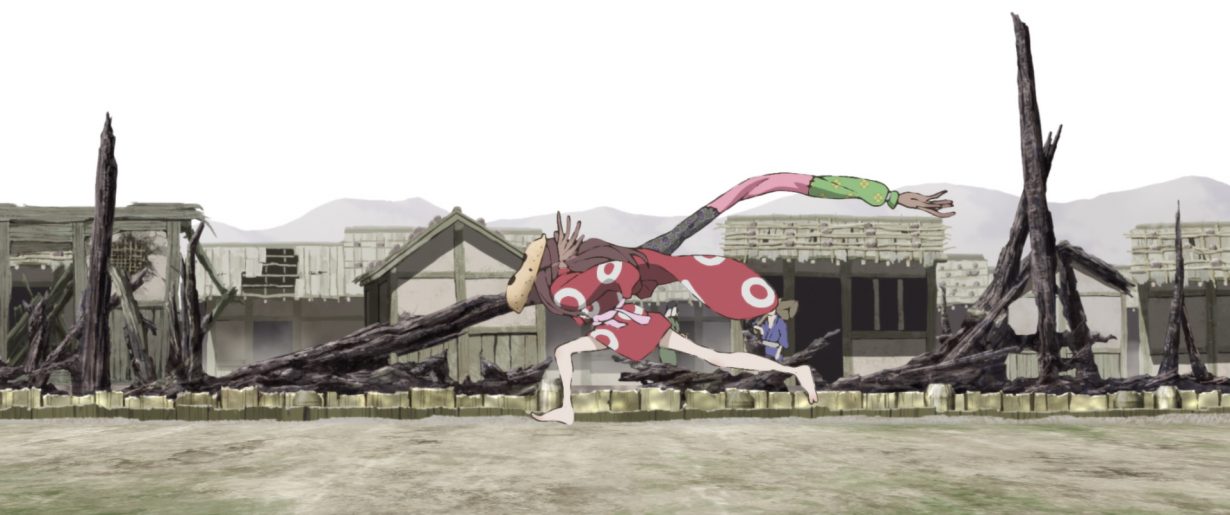

The titular Inu-Oh (‘Dog King’) is a nameless boy who is born cursed, after his father sacrifices his soul to attain an ancient Heike artefact. In the opening scene, he slides out of his mother’s womb with a patchwork body – comprising the distended limbs of 100 dead Heike soldiers, and a disfigured face that he hides behind a gourd mask. Immediately abandoned as a baby, Inu-Oh is left with only stray canines for friends. He grows up defiant, embracing his position as an outcast: he regularly terrorises villagers and stalks the margins of his birth family’s home. Yet there is a yearning within him to participate in his family’s craft of sarugaku, a nascent form of Noh in which stories are told, via acrobatic dance, juggling and pantomime, to the rhythmic beat of taiko drums. Inu-Oh fulfils his dream when he meets Tomona, a biwa player from a scattered order of blind priests who keep the stories of the decimated Heike clan alive through song. Inu-Oh learns he can break his curse by telling the stories of the Heike, while Tomona realises he can keep his dying culture alive through Inu-Oh’s talent. It’s only natural for the two boys to combine their separate artforms to tell Heike tales, creating intoxicating musical experiences that attract larger and larger audiences from neighbouring villages.

This is where Yuasa’s gonzo sensibility comes in: he adapts the stories into glam rock anthems, with Inu-Oh’s stunning vocal range (courtesy of nonbinary singer Avu-chan) evoking the versatility of glam icon Freddie Mercury, while his stage persona mirrors that of Iggy Pop. The anachronism of a stadium concert – replete with fire-twirling, headbanging and high-tech light shows – in fourteenth-century Japan may be a shock to period pedants. But in the vein of a Baz Luhrmann musical, it demonstrates how Noh theatre must have felt to new audiences, all those centuries ago, confronted with this electrifying fusion of storytelling, performance and mysticism.

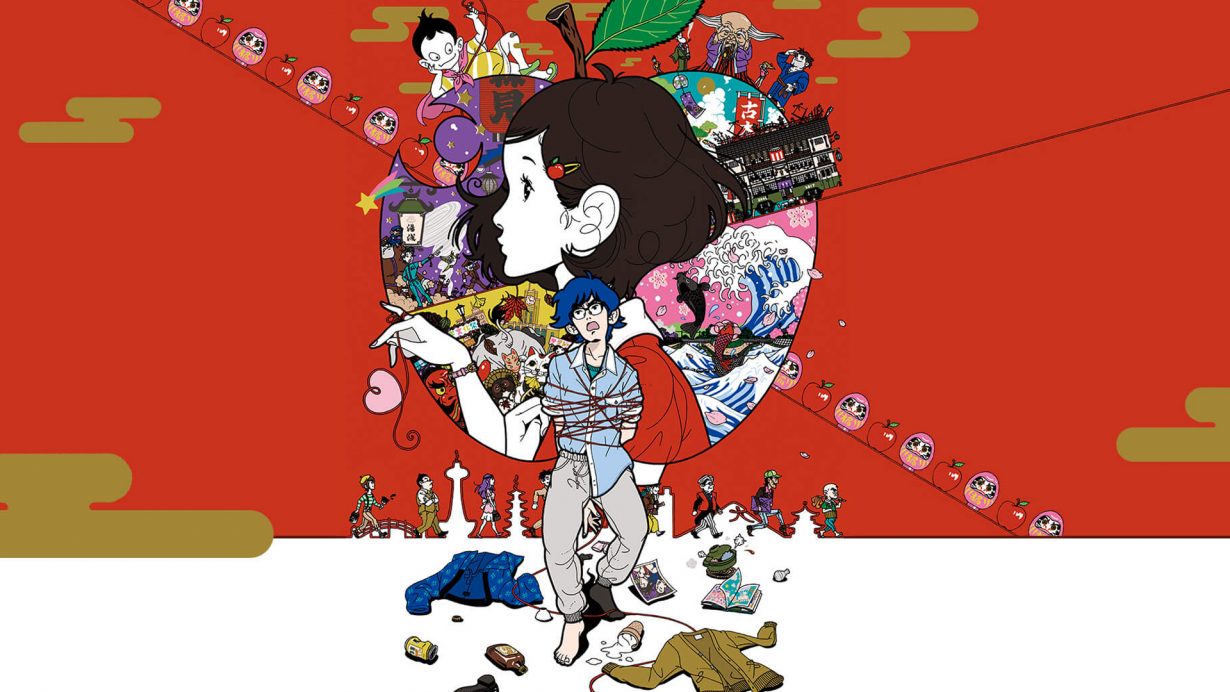

Poster for Night Is Short, Walk On Girl, 2017, dir Masaaki Yuasa. © Tomohiko Morimi, Kadokawa / Nakame Committee

A dynamic relationship between music and animation is common in Yuasa’s work: 2017’s Night Is Short, Walk On Girl features hallucinogenic passages that mirror the score’s operatic interludes and more up-tempo tracks from Japanese alt-rock band Asian Kung-Fu Generation. Further, in Yuasa’s guest episode of Adventure Time, main characters Finn and Jake are transformed into birds to the beat of a chirpy dance remix of Mozart’s Queen of the Night aria (from The Magic Flute, 1791). In Inu-Oh the flamboyance and gender nonconformity of glam rock informs the rebellious spirit of the two boys who have always existed on the margins: throughout the film, both characters are threatened by erasure and violence, facing disapproval from both the ruling Genji state and biwa traditionalists. Though set centuries in the past, the film includes flashes to present-day Tokyo – reminding the audience that its themes of gender fluidity and oppression are tied to the contemporary struggles of queer communities in Japan, and worldwide. Conversely, it stands witness to socially marginalised people like Inu-Oh and Tomona who have existed throughout history, with the characters’ struggle to preserve Heike culture mirroring their internal struggle to be heard, and to be remembered. In the face of looming tragedy, Inu-Oh and Tomona continue to rock out, becoming increasingly androgynous in the process: Inu-Oh takes on a Bowie-esque appearance, while Tomona grows his hair long and begins wearing geisha makeup. Tomona also chooses a new name for himself – Tomoari – marking a new era, where his sense of self is both marked by the past and transformed into something vibrantly new.

A capacity for the new, for the unexpected, defines Yuasa’s work. One of Mind Game’s most memorable sequences depicts Nishi’s meeting with God, who shifts from a titanic crystal being into a text-based interface, before bursting into an ever-changing procession of friendly, Looney Tunes-esque cartoons. “You can’t decide what I should look like!” God quips, as the elastic animation reflects our elastic conceptions of spirituality. Meanwhile, Inu-Oh and Tomoari’s first meeting (and jam session) is shot in feverish camera rolls, as the two swirl into the stars and eventually become one entity. Moments like these cement Yuasa as one of the greatest animators living today – a filmmaker unafraid to tap into the wackiness of his chosen medium, uncover unspeakable desires and indulge in sincere creative transcendence.