For decades, Albert York’s bounteous paintings have hidden in plain sight. Aficionados of deceptively substantial landscape and still-life painting, such as the critic Bruce Hainley, have long revered him; I first heard about York a few years ago from some savvy painter friends, and was speedily entranced. Calvin Tomkins, in a 1995 New Yorker essay, called him ‘the most highly admired unknown artist in America’, a précis still applicable when York died in 2009. Last year, though, his art landed under a gilded spotlight, as the gallerist Matthew Marks, who began collecting York’s paintings during the early 1980s, organised, with ArtReview’s own contributing editor Joshua Mack and via, apparently, some painstaking loan-brokering, the first major show of his work outside of York’s longstanding gallery, Davis & Langdale. That’s how come we have this book, which displaces William Corbett’s lovely, personal but slim Albert York (2010) as the essential volume on the artist.

Reproducing some 60 paintings and drawings along with vintage press clippings, and augmenting the republished Tomkins essay and another archival piece by Fairfield Porter with a typically off-beam and questing piece by Hainley, it’s a gorgeous, serious-minded thing. York wouldn’t have looked at it, and wouldn’t have visited the show if he were alive. The one time he went to a museum to see his work, in 1989, it effectively precipitated his giving up painting; in so doing, he was retreating into a shell within a shell. Already by the early 1960s, when York began making his tough, lyrical still lifes (influenced by Albert Pinkham Ryder and, Hainley guesses, more by Porter and other American Pop-resistant, abstraction-aware figurative painters than York let on), he had quit Manhattan as fast as he was able, settling his family upstate, delivering his paintings wrapped in brown paper. When, during the 1970s, he came into some money and depended less on selling his art, his gallery found it harder and harder to get work out of him at all. One pictures him painting, but also just standing in a field, staring intently at a tree or a cow.

That’s because what his paintings feel like is the rare, quicksilver instant when reality’s curtains flick apart and looking becomes transcendent. Take Twin Trees (c. 1963). It’s approximately describable: a fuzzy, bronzy view of trees flanking a pond in which one of them is reflected. God knows what time of day or night it is – the scene looks dipped in precious metals. The painting, paring back detail yet containing all it needs to get across, is almost all atmosphere, and sanctions critical flights: Porter, in the 1975 catalogue essay reprinted here, sees the trees as ‘Baucis and Philemon after Zeus, at their death, changed them into trees to grant them their desire never to be separated’.

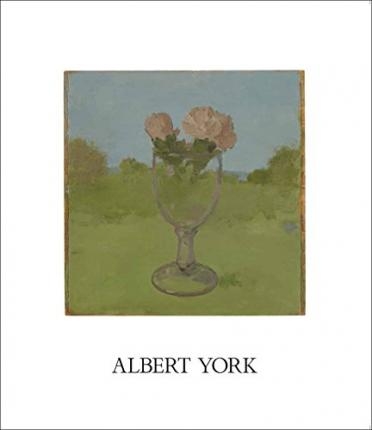

York mostly painted landscapes, animals and still lifes of flowers, on rough sheets of timber. Within this narrow, traditionalist focus – expanded, later, into occasional peculiar scenes of Native Americans and floating figures – he made vision, in the vernacular and exalted senses, the subject of his work. Closing in on the broken-stemmed pink flowers of Two Zinnias (c. 1965), or the Two Pink Anemones in a Glass Vase in a Landscape (1982), he invests them with an architectural massiveness that both reveals his understanding of Morandi and makes the viewer feel like an excitable Lilliputian. When, as in Cow (c. 1972), he paints the animal looking away as it stands in murky submarine light, what that cow is looking at or thinking about feels large, deep and incommunicable. You can spend a long time networking York’s work together, wondering what kind of agents the occasional figures are – though his animals are characters too – but it guards its secrets, while spilling suggestion. It’s the work of someone stunned, yet given voice, by the visible and the invisible that shadows it.

Possibly because of the gulf between what he saw and what it’s possible to convey in paint, however, York’s work constantly dissatisfied him. Asked by Tomkins if he’d ‘ever found any real satisfaction in his work’, York replied: ‘Not really. Only one panel, maybe.’ His work, he said, ‘had no relation to good painting’. He may have been right, by his own Olympian standards. But he was fully wrong by realistic ones, and Albert York offers 184 pages of proof.

This article was first published in the March 2015 issue.