Editor’s Note: Last year Bangladeshi filmmaker Naeem Mohaiemen presented two films, Tripoli Cancelled and Two Meetings at a Funeral (both 2017) at Documenta 14. The former, along with Volume Eleven (flaw in the algorithm of cosmopolitanism) (2016), is currently on show at MoMA PS1 through 11 March

Naeem Mohaiemen, based in Dhaka and New York, is an artist in the most expanded sense: he is as likely to produce essays and research notes as he is works destined for exhibition. For sure, he makes films (the most recent, The Young Man Was (Part 1: United Red Army), 2011, is the first in a proposed trilogy) as well as occasional sculpture and photo works (I Have Killed Pharaoh and I’m Not Afraid to Die, 2010, for example) but one gets the impression they took those forms simply because of their suitability to a particular iteration of Mohaiemen’s big idea. And that idea is a longstanding, evolving study of the international left (and its various, often conflicting attempts towards creating a society founded on ideals of equality) through the prism of anecdotal historical incidents.

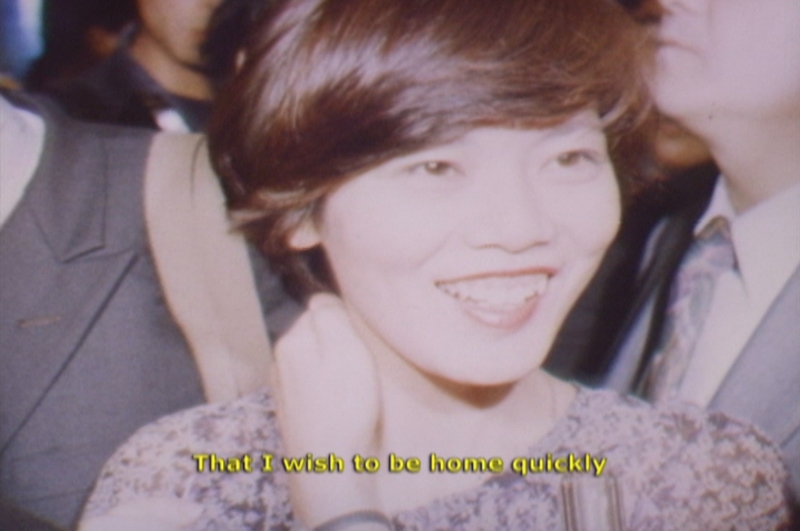

The first part of United Red Army – lasting over an hour and shown at both the Sharjah and Momentum biennials last year – plays out the crackly 1973 audio recordings of negotiations between a member of the Japanese Red Army onboard a hijacked Japanese Airways airplane grounded at Dhaka airport and a Bangladeshi official. It’s suspenseful, addictive listening. Mohaiemen weaves this dialogue with narrative and visual tangents inspired by the details of the incident: we learn that the artist, growing up in Dhaka, watched the hijack standoff live on television as a nine-year-old when it interrupted his favourite television series (a serial about a group of ageing resistance fighters, from which we are treated to clips). We learn about the minor film career of one of the captured passengers through more filmic nuggets, collaged with contemporary local and international news reports. The overall effect is an engrossing engagement with the event both on a micro, localised level and within its dizzying historical political context.

This profiling of an archival snapshot as a juncture in the progression of the history of the radical left is also present in Sartre Kommt nach Stammheim (2007), in which the artist recounts, via a text-and-image collage, the 1974 meeting between Jean-Paul Sartre, a figurehead for socialism’s older incarnation, and the imprisoned, nihilistic Andreas Baader, one of the leaders of Germany’s Red Army Faction. Here, as in much of Mohaiemen’s multifaceted practice (and despite the plotted comic moments that are raised in these films and essays), a pensive melancholia for something lost – or a project that has come to ruin – pervades.

This article originally appeared in the March 2012 issue.