The artist’s largescale paintings at Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia capture the miraculous and enigmatic nature of both new parenthood and the vagaries of artmaking

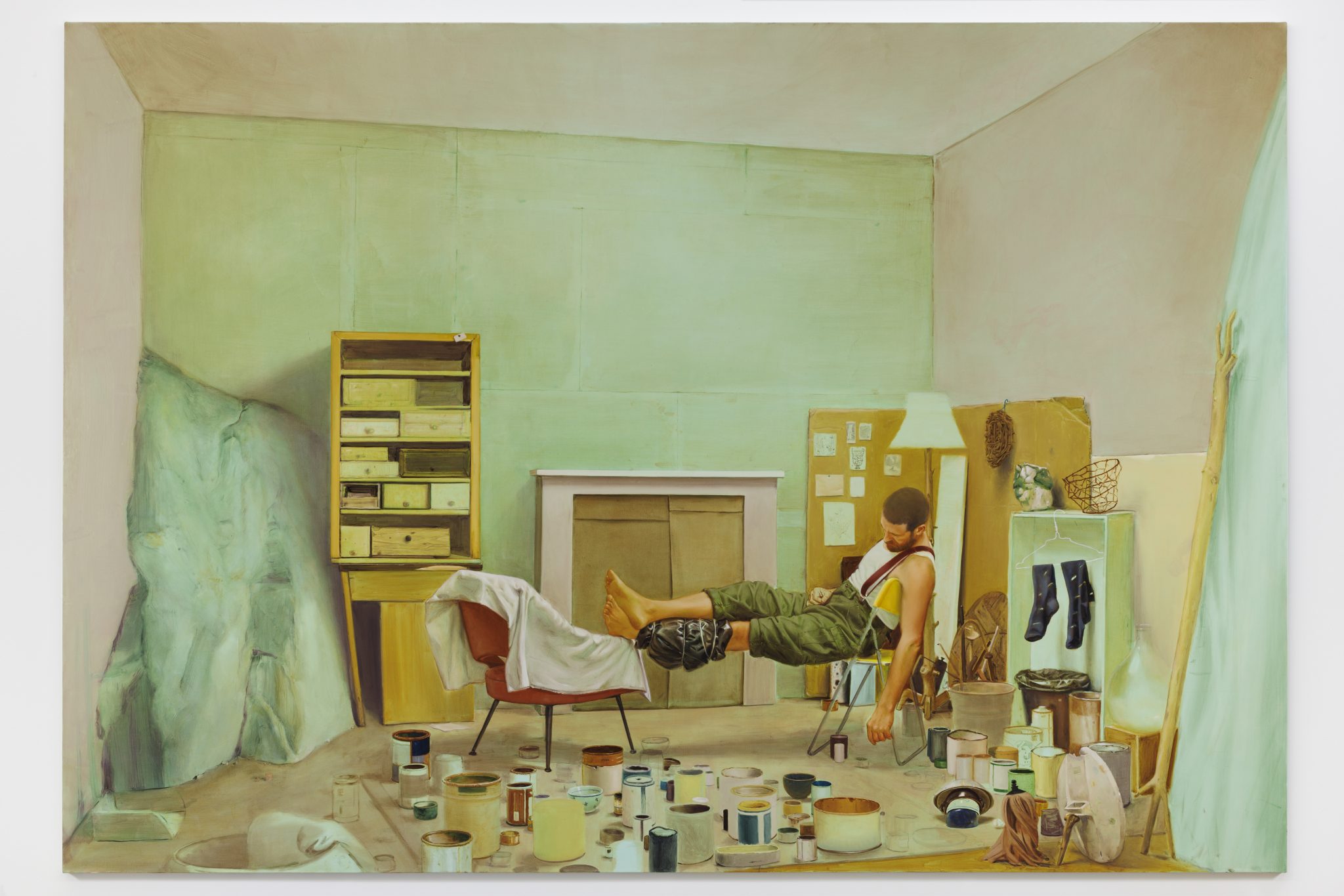

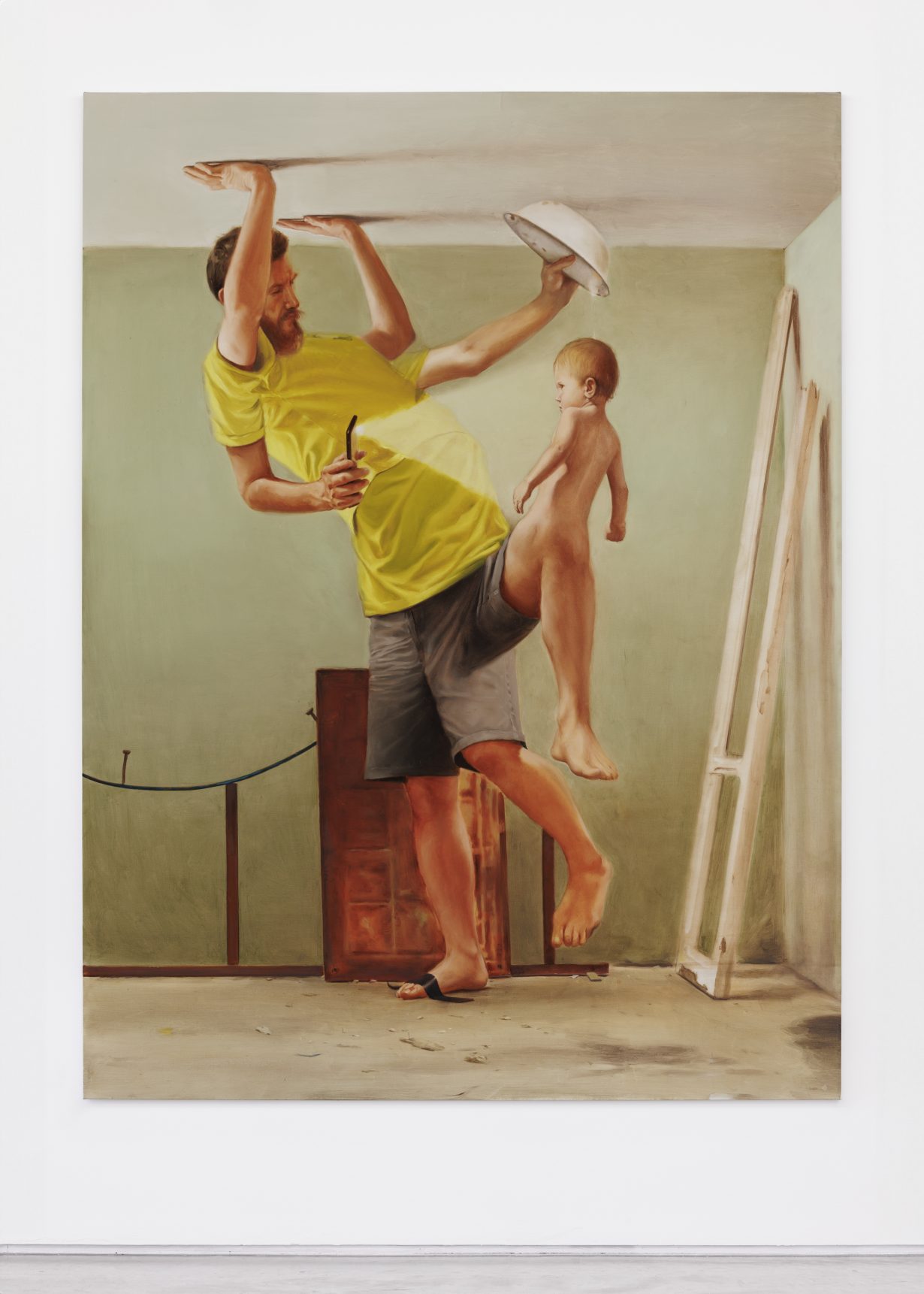

In Reggio Emilia, the compact Italian city where the Collezione Maramotti’s exhibition space is located, there’s a church that contains a 1570s fresco of the Virgin and Child by Giovanni Bianchi, aka Bertone. In 1596, according to local legend, a deaf-mute teenage boy stood in front of this image and could suddenly hear and speak; the Church verified the miracle and Reggio joined the pilgrimage list. Upon the fresco’s frame is the phrase ‘Quem Genuit Adoravit’ (approximately, ‘she adored whom she begat’), and four centuries later this phrase serves to title Manuele Cerutti’s show of six large, off-beat, jewel-toned oil paintings, two small ones, and 31 tightly worked pencil sketches and watercolours. The Turin-based artist, the gallery handout tells us, himself became a parent not long ago, and his small son appears throughout, accompanied by a crop-headed, bearded adult male who closely resembles the artist. But there are no beatific Madonnas here; rather, there’s a hard-won, idiosyncratic, fictional miracolo. Across the cycle of canvases and via some arcane, mostly offstage alchemical process, a boychild sprouts from the man’s left leg. This kid feels equally like a real person and a transparent metaphor for the dual inscrutabilities of creativity and parenthood, the images seemingly the work of someone who, in the studio and the home, has become accustomed to squinting bemusedly and saying to himself, ‘where did that come from?’ In Tutte le mani dormono (All Hands Are Asleep, 2023–24) Cerutti’s stand-in naps in his aquamarine, paint-pot-studded studio while sporting a workingman’s vest and braces. Tied around his left calf with string is a black plastic bag; this, the handout says, refers to marcotting, a technique of encouraging new growths on the stems or branches of plants. Other works show him at varying waystations on a mysterious route to male pregnancy. In Perdere l’eroe conservare la ferita (Losing the Hero Sustains the Wound, 2023–24) he appears in the foreground beneath an underpass, smearing something on his leg out of a bucket. In the background, he reappears several times along a path curving away to the landscape (referencing how Bible stories are often narrated in early Renaissance paintings); variously making weird hand gestures, finding his leg turning glowingly transparent and passed out in the dirt.

In other compositions, we see him turning a sickly green in face and hand, dividing into multiple avatars who sometimes perch on each other’s shoulders, and finally, postmarcotting, sporting his conjoined offspring. In the secular ceremonial of Meriti e colpe (Merits and Faults, 2022–24), the man – now with slightly longer hair and beard, plus four arms and three legs for domestic multitasking – anoints his conjoined descendant with liquid from an enamelled bowl while illuminating his face with his smartphone’s torch. Aside from the weird gardening-genesis narrative and filtered adoration that powers these works, though, it’s often left open what’s really happening across them, an aspect encouraged by the seemingly achronological hang, and in a manner that recalls looking at ecclesiastical artworks whose storylines and dogmas we’re distanced from. As a result, the show sustains a haloing and persuasive enigma that aligns with both the fumbling and awed nature of new parenthood and the vagaries of artmaking. The one thing a viewer can truly ascertain from QUEM GENUIT ADORAVIT, which elides motherhood entirely, is that Cerutti must have a very understanding partner.

QUEM GENUIT ADORAVIT at Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, through 28 July