The subgenre’s recent revival in film and art suggests that the human isn’t what it used to be

“You are everything they want me to be,” says Elisabeth as she confronts her younger self, Sue, in Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance (2024), one of the most discussed and divisive Hollywood movies of the past year. The film sees Elisabeth, played by Demi Moore, strike a Faustian pact with a shadowy corporation to create Sue, a youthful and ‘more perfect’ doppelgänger that pushes its way out of her body. As Sue misbehaves, Elisabeth’s body is punished. The film’s politics are literal – Moore’s ageing Hollywood actress must answer to a repulsive film executive called… Harvey.

Yet the film also stands as a hypercontemporary reflection of body horror, the eternally multivalent popular genre that has the uncanny knack of serving as a barometer for society’s disparate, unspoken anxieties. The significance of Elisabeth’s plight extends beyond the politics of beauty and ageing by exploring the dissolution of the human body as we once knew it. Visualised onscreen by independent auteurs like David Cronenberg and Andrzej Zuławski, body horror has historically externalised cultural fears through grotesque transformations of the human form. Cronenberg’s films, like Rabid (1977), Videodrome (1983) and The Fly (1986), dissect the fusion of flesh and machinery, often reflecting anxieties about media, surveillance and the female body. Zuławski, through Possession (1981), portrays the monstrous feminine as both terrifying and liberating in its depiction of a servile housewife in West Berlin during the height of the Cold War, embarking on an inner journey of sexual transgression. Fears change for each generation: where once the genre focused on disease, parasites and governmental and technological control, it now speaks to an age shaped by virtual experience, digital dysmorphia and a growing detachment between the physical and virtual self. Today our anxieties are embodied in the convergence of flesh and machine, in genetic manipulation and, postpandemic, in the liminality of human-animal hybridity.

Cronenberg’s seminal Videodrome directly anticipated such anxieties. The film’s protagonist, Max Renn, descends into a hallucinatory nightmare as his body is reshaped to the point of destruction by the television signals he consumes. In his final moments, he embraces his metamorphosis with the phrase: “Long live the new flesh”. This prophecy encapsulates the genre’s trajectory towards a future where identity is unfixed, bodies are mutable and the self is controlled by external forces.

Over the last year, the genre has explored the porous boundaries of the human form through reproductive ethics, biotechnology, animal hybridity and virtual avatars. Recent films like Max Minghella’s Shell and Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man (both 2024) depict bodily transformation as a symptom of a world in which a person is no longer anchored to an organic, warm-blooded form. But the new flesh is not confined to film. Contemporary visual artists are increasingly engaged with themes of bodily disintegration, transformation and commodification. Mire Lee’s Open Wound (2024) saw fleshy, lubricated silicone sculptures hang from the ceiling of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Amid the vogue for gut health, these seemingly still-digesting intestines evoked anxieties around medical interventions, biotech and the vulnerability of the body to microscopic entities. Lee works within the legacy of Korean sculptors like Lee Bul, whose art envisions cybernetic augmentation; yet Mire Lee’s work also owes much to Cronenberg in the suggestion that bodily manipulation is often violent, invasive and inescapable.

Fans of Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) would not anticipate a kinship with the work of Tracey Emin, yet the once Young British Artist’s exhibition I Followed You to the End, on show last autumn at White Cube Bermondsey, visually interpreted cancer as a bodily invasion by a terrifying alien presence. Emin openly documented her battle with a malignant growth in her bladder, placing films of her stoma bag at the centre of the show. Her raw documentation of her suffering body fighting an internal mutation chimed with a world increasingly fixated by the fragility of the human experience.

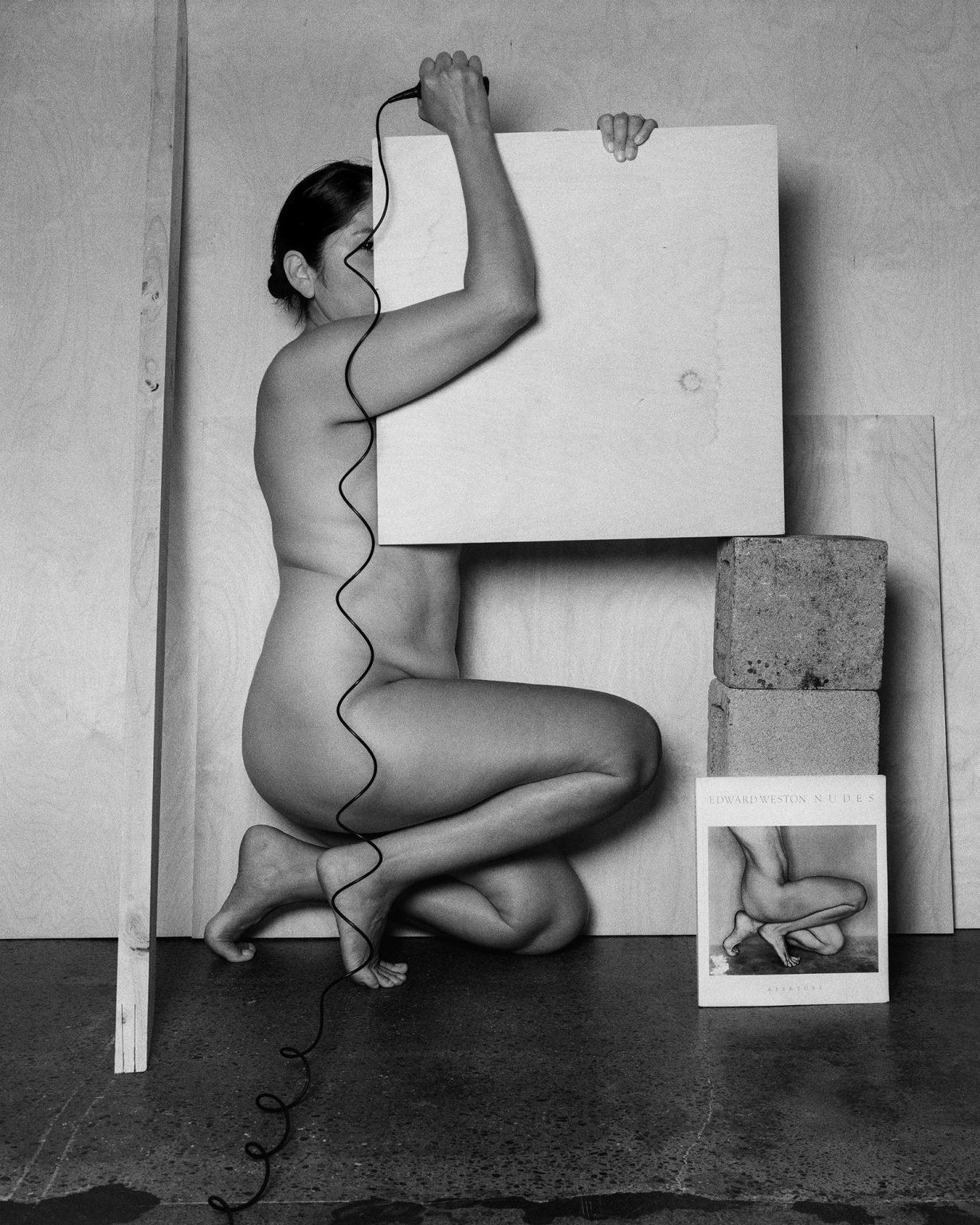

Similar themes have also been explored more subtly in contemporary photography. The self-portraits of Peruvian-born American artist Tarrah Krajnak (currently shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize) use deft and sharp collage to interpret identity as a frac-tured, unstable construct, one vulnerable to outside control. Krajnak’s often irreverent work might not so obviously align with the body horror tradition. Yet rather than externalising fear in grotesque physical mutations, she uses the momentary nature of photography to explore how our sense of uniqueness is increasingly blurred and shaped by forces beyond our autonomous control. Her work suggests that horror does not solely emerge from bodily corruption, but from the collapse of self in the face of external pressure.

This thematic expansion is not limited to the organic body. The new flesh in an era of AI-generated aesthetics means the human form can be endlessly morphed, erased or enhanced, and art has the capacity to capture the increasingly accepted fact that digital dysmorphia isn’t merely a passing psychological concern but a fundamental and permanent transformation. French body artist ORLAN has long explored the fragility of the human form through performance, digital art, photography and film, with recent work that incorporates AI-generated imagery and 3D modelling onto her own body to critique beauty standards and bodily commodification. Andrew Thomas Huang’s AI-generated animations depict the human body in constant metamorphosis. Such works illustrate the dawning realisation that the grotesque mutations once confined to the realm of film are now an everyday reality on social media. Here, behind our screens, the collapsing boundaries between real and artificial bodies – once imagined in Videodrome – are becoming normalised.

Instead of the cinema screen or radical gallery space, the locale of bodily horror is now Instagram and TikTok: infinite virtual landscapes in which the self is endlessly malleable, subject to constant revision, external modification and rampant sexualisation. In her 2020 book, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, American writer and curator Legacy Russell writes: ‘A glitch is an error, a mistake, a failure to function. Within technoculture, a glitch is a part of machinic anxiety, an indicator of something having gone wrong.’

Russell calls on women to reclaim bodily errors – glitches – against patriarchal and capitalist structures. ‘Within glitch feminism, a glitch is celebrated as a vehicle of refusal, a strategy of nonperformance,’ she writes. ‘This glitch aims to make abstract again that which has been forced into an uncomfortable and ill-defined material; the body.’ Today, horror is found in our struggle to do as Russell instructs to reclaim one’s glitches, and not to succumb to society’s thirst for an increasingly unreal standard of beauty; what Jia Tolentino, writing in The New Yorker, has coined ‘Instagram face’.

Long before Hollywood’s rediscovery of body horror, Chinese artists like LuYang and Cao Fei were articulating these concerns in the digital realm. LuYang’s LuYang Delusional Mandala (2015) and DOKU series (2020–) depict AI-generated avatars undergoing grotesque mutations, bodies warping and melting in a virtual landscape. These digital works extend horror into the realm of the cybernetic, where the body is no longer a physical construct but a mutable, disposable entity. Similarly, Cao Fei’s RMB City (2007–11) constructs a dystopian virtuality in which human forms are mere disposable commodities. These works materialise Cronenberg’s vision of technology reshaping the body. Here, selfhood bows to the might of algorithms. Our DNA is now reconfigured as digital detritus.

In today’s body horror renaissance, gore is a metaphor for a larger existential crisis. We’re entering an era in which human existence will be defined by the interplay between biology, technology and digital representation, no longer reliant on soft flesh and brittle bones. Yet, by the same token, the body is no longer the sole property of the self. It is a battleground, contested by medical advancements, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence and the relentless aesthetic pressures of visual culture. The horror lies not in the loss of bodily control, but in the realisation that selfhood no longer need be embodied. “You can have everything you want, but you’ll never be her,” says Sue, the younger doppelgänger of Elisabeth. The new flesh is here, and we all fear falling apart.

Tom Seymour is a writer based in London

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.